by Sumaira Quraishi

Trigger warnings: rape, invasive medical procedures, and medical malpractice.

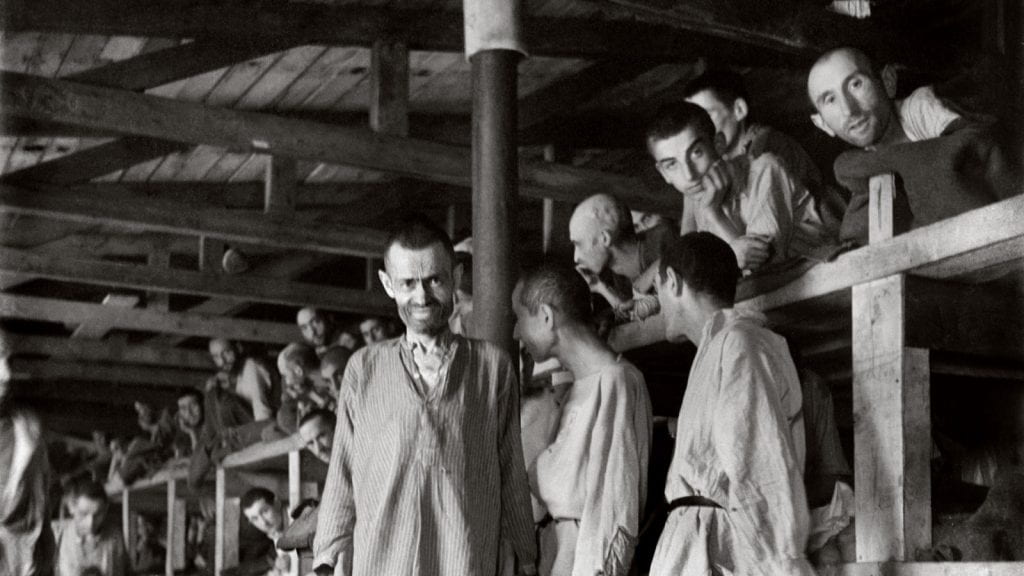

Often, the Supreme Court of the United States is seen as a paragon of the American legal system and the national values it strives to uphold. At least, it used to be. While trust in the sanctity of the Supreme Court has recently been broken over controversial political issues, the Supreme Court is no stranger to making unfavorable and borderline unconstitutional rulings in cases brought before the justices at the time. While this is to be expected, with the court switching from conservative to liberal-dominant every so often, some cases seem to concern unalienable human rights that have been denied by the court, as expected of a supposed higher authority that is ultimately, and always will be, a product of its time. In 1927, Carrie Buck learned just how fallible the highest court in the American legal system could be when infiltrated with an ideology eventually perpetuated by the Nazi party during World War I.

The Birth of Eugenics

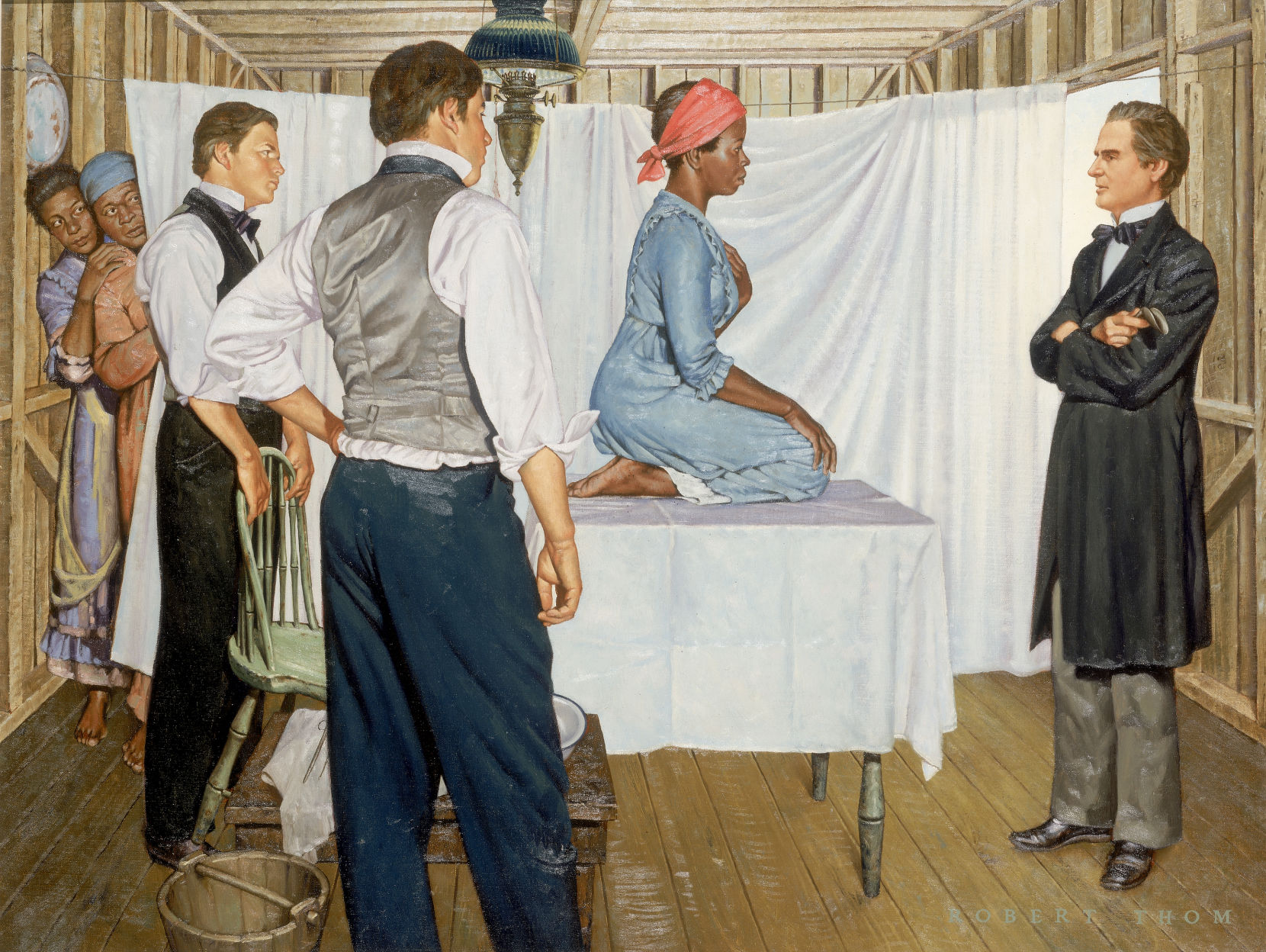

Surprisingly, and perhaps horrifyingly, eugenics was not the child of oppressive or violent regimes, but the culmination of centuries of scientific research and racism woven together and spread through communities worldwide during the early 20th century. Eugenics was a theory created to exterminate certain people who were not considered mentally fit, genetically clean, or conventionally attractive. The ones who decided the people that fit into these categories usually were ones in positions of power or influence in society: doctors, politicians, and scientists. Favored methods for perpetuating eugenics were forced sterilization, societal segregation, and social exclusion, all of which seem to be methods straight out of the time of slavery where eugenicists drew inspiration and justification for eugenics.

In the modern age, there is a laser-like focus on women’s rights to not have a child, and while this pursuit of maintaining women’s rights is justified, for many vulnerable men and women today the fight for the right to have a child is just as in need of attention. An old theory about the superiority of white, able-bodied people may seem like one to be thrown into the history books and mentioned alongside other conventionally shunned snippets of history in the modern discourse, however, eugenics never truly went away.

Eugenics Still Lingers

Overshadowing lives today as a phantom of the eugenics school of thought, a forgotten Supreme Court case in 1927 named Buck v. Bell led to the codification of sterilizing those deemed “feeble-minded” and genetically inferior by people in positions of power into law. Carrie Buck was a woman who resided in a mental institution and became pregnant after being raped, resulting in staff at the asylum taking acute notice of Buck. Doctors and directors at the asylum were firmly entrenched in the eugenics culture sweeping across America and firmly believed Buck should not be allowed to carry to term. These men took the stand that Buck should be forcibly sterilized to prevent her genes from being passed on, and the Supreme Court was in full agreement, with the justification for the ruling against Buck being that she had a history of mental illness back to one of her grandmothers and being sterilized would protect the goodness of society by keeping “feeble-minded” and “promiscuous” people from reproducing.

Not only is Buck v. Bell an appalling ruling that trod on the constitutional rights of Buck, but it also opened the door for forced sterilization procedures to continue without secrecy and, chillingly, has never been overturned. An old legal case from the 1920s may seem like something to be stored away in textbooks and forgotten, yet, eugenics practices in the form of forced sterilizations are happening today

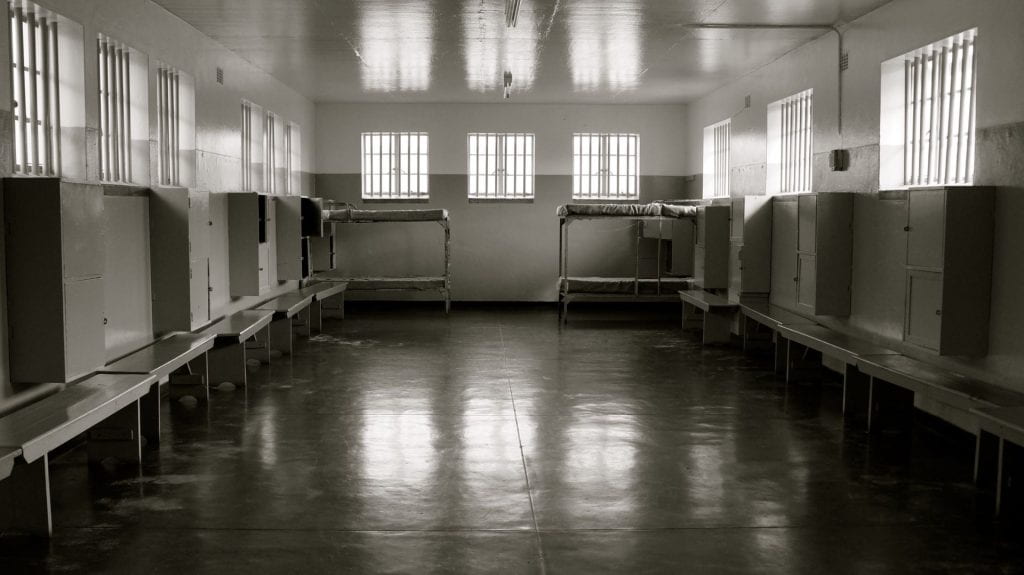

In California between 2006 and 2010, almost 150 women in two different prisons were given hysterectomies without their consent or legal documentation authorized by the state, with 100 suspected cases of sterilization dating back to 1997 uncovered as well. Furthermore, in 2017 a Tennessee judge offered to reduce prison sentences by 30 days for any inmate who signed up to receive a birth control implant or a vasectomy. The latest case of eugenics rearing its head in American practices was in 2020 when it was revealed that hysterectomies were being performed illegally on women in the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention centers. These cases are not the only ones concerning the continued use of forced sterilizations to prevent incarcerated or institutionalized individuals from having the right to choose to have a child, with many more subject to the archaic practice who have yet to have their story told. These practices are considered morally reprehensible by the general public but can trace their roots to eugenic procedures approved by the Supreme Court in a case that was challenged but never overturned, and some laws approving the use of sterilizations are still in existence in states such as Virginia.

What Can Be Done

Fighting a system that has failed a large portion of the American population, and pushing for a Supreme Court ruling to be overturned when the nation’s political climate seems fit to burst with elections on the horizon can seem incredibly intimidating. These thoughts are not unfounded, but what government bodies forget is that their power comes from their people and constituents. Harmful practices can be challenged with public favor and fervor. Staying informed on what influences modern atrocities like Buck v. Bell and knowing that the majority of the population supports upholding the 14th Amendment protecting civil liberties keeps people motivated to improve the lives of their fellow Americans. Leaving Buck v. Bell as a precedent in U.S. law allows for unprotected groups of individuals who are incarcerated or institutionalized to be at heightened risk of human rights abuse, and while forced sterilization is morally reprehensible, the law does not currently outline sterilization as illegal since the Supreme Court ruling remains standing. Reaching out to local or state politicians is an option for those who want to appeal hurtful laws, and a less intimidating option is to join advocacy groups whose views align with your own.

For more information on another situation involving eugenic practices ruining the lives of nonincarcerated individuals, the case of a fertility doctor who artificially inseminated dozens of his clients with his sperm and remains free from jail can be found here.