The Rohingya, a stateless Muslim ethnic minority, have been the victims of a decades-long ethnic cleansing campaign. Their native country, Myanmar, does not recognize them as citizens; because of this, they are denied basic rights. In 2017, over 742,000 Rohingya were forcibly displaced to refugee camps in neighboring Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, following mass killings and attacks on their villages. More have been displaced after a 2021 military coup and subsequent civil war.

UN’s High-Level Conference on Rohingya Muslims and Other Minorities in Myanmar

On September 30, 2025, the UN held a conference on the Rohingya population, which hosted speakers including Rohingya leader Lucky Karim, the Bangladesh interim leader Muhammad Yunus, and Wai Wai Nu, the executive director of the Women’s Peace Network-Myanmar. Speakers urged the international community to take immediate action for the protection of the Rohingya people. The impacts of aid cuts, the necessity of sanctions on Myanmar, and the importance of immediate repatriation of Rohingya to their homeland were discussed.

Background: A Long History, 2017 mass expulsion, and Ongoing Civil War

Ethnic tensions between the Rohingya minority and the Buddhist majority ethnic groups existed long before the 2017 mass exodus of Rohingya to Bangladesh. In 1982, Myanmar’s government denied the Rohingyas’ status as an ethnic group, making them stateless. In 2017, following Rohingya militant attacks on police outposts, Myanmar’s troops and local mobs attacked and burned Rohingya villages, killing 6,700 Rohingya and perpetrating sexual violence on women and girls.

Following these atrocities, cases were filed in the International Criminal Court (ICC) and the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on behalf of the Rohingya, which are still pending. Most Rohingya fled to Bangladesh as refugees, where over a million remain in refugee camps.

In 2021, civil war broke out following a military coup in Myanmar. After years of an unsteady power-sharing agreement between the military and democratically elected leaders, the military declared the 2020 election, won by the National League for Democracy (NLD), illegitimate. Myriad forces opposed the military junta, forming pro-democracy coalitions and ethnic rebel militant groups, like the Arakan Army.

The Arakan Army currently controls most of the Rakhine State and the Myanmar-Bangladesh border. Rohingya are caught in the middle of the civil war. Rohingya have reported massive restrictions on freedoms under the Arakan Army control, and other human rights abuses like extrajudicial killings and forced labor.

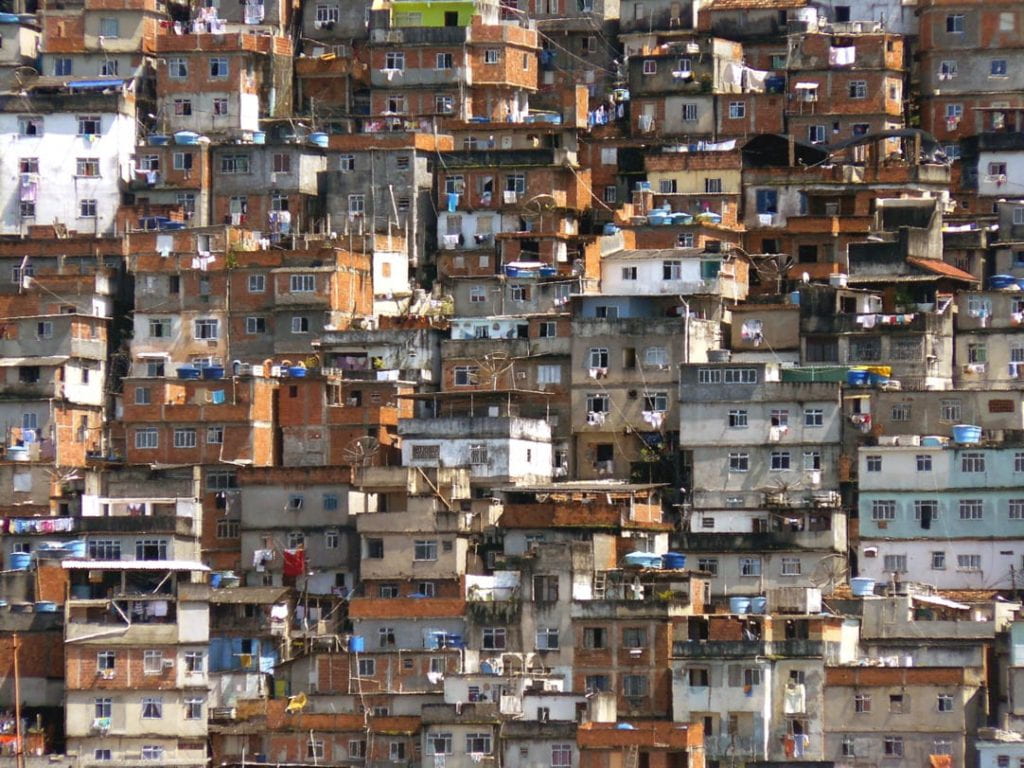

Displacement in Bangladesh

Over one million Rohingya now live in dire conditions in refugee camps in Bangladesh. They rely almost entirely on international humanitarian aid and are largely unable to find work. Bangladesh’s interim leader, Yunus, told the UN during the Conference that Bangladesh is “forced to bear huge financial, social and environmental costs” due to the refugee crisis. Following aid cuts, particularly those made by the Trump administration to USAID, non-emergency medical care and food resources provided by the World Food Program were drastically reduced, exacerbating an already grim situation. At the Conference, the US pledged $60 million to support Rohingya refugees while urging other governments and organizations to step up.

Repatriation

While the Bangladeshi government and the Rohingya themselves hope for repatriation back to Myanmar, the conditions are still too hostile for immediate return. Both the military junta and Arakan Army are accused of grave human rights abuses against Rohingya, and if the Rohingya returned, their situation might be even more dangerous than in the poorly funded Bangladeshi camps. A Human Rights Watch investigation revealed that the Arakan Army has committed widespread arson on Rohingya villages and stoked ethnic tensions by unlawfully recruiting Rohingya men and boys.

Rohingya representatives at the UN Conference stated their need for international protection to make progress toward the Rohingyas’ return to Myanmar. Rofik Husson, Founder of the Arakan Youth Peace Network, reiterated the wish of Rohingyas to live in their “ancestral homeland with safety and security.” He added that the issue of Rohingya repatriation and safety is a “test for this Assembly and a test for humanity itself.”

While the chances of repatriation to Myanmar remain slim, other actions must be taken to improve the situation of Rohingya refugees. Funding shortfalls, limited mobility, and a lack of formal education have cost the Rohingya their freedom and livelihoods.

Conference Shortfalls, Outside Solutions

UN Representative Statements: UN delegates from across the world offered different perspectives on the Rohingya situation, as outlined by the United Nations’ press release regarding the Conference. Myanmar’s delegate to the UN urged the international community to reject the military junta’s planned December election as illegitimate, stating that the military is the root of Myanmar’s crisis. The representative of Poland condemned the employment of advanced military technologies on civilians, while Türkiye’s representative urged Myanmar to comply with the International Court of Justice. China’s delegate warned against politicizing human rights and called for dialogue between Bangladesh and Myanmar.

Few concrete commitments were made at the Conference for improving the Rohingyas’ situation, other than international aid offered by the US and UK, which still does not bridge the funding gap required to create decent and stable conditions within the Cox’s Bazar camps. The Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights organization suggested some solutions to the international community following the conference. These include:

- Reduce mobility restrictions to allow for development and reduce aid dependency within Cox’s Bazar camps

- Regional states recognize Rohingya as refugees and ensure refugees do not return to Myanmar under detrimental conditions (also called non-refoulement)

- Refer the Myanmar situation to the ICC while U.N. member states prosecute individual perpetrators under the principle of universal jurisdiction

- Impose an embargo on military supplies to Myanmar and reject the military junta as illegitimate

Rohingya Perspectives on Their History and Future

Perhaps the most powerful and illuminating moments from the Conference came from the Rohingya representatives themselves, however. The first Rohingya to attend New York University, Maung Sawyeddollah, emphasized the international community’s role in empowering the Rohingya community, particularly through higher education. He urged universities to give lifelines to Rohingya students, who lack access to formal education in refugee camps. “It’s not a big burden for a university to offer one or two scholarships to Rohingya students in an academic year,” Sawyeddollah stated.

Lucky Karim recounted fleeing Myanmar in 2017 to Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, and then her return to the camp years later. She stressed that the genocide of the Rohingya is not an isolated event. It did not begin or end with the 2017 mass expulsion to Bangladesh, stating, “Rohingya have been refugees to Bangladesh numerous times, even before 2017, and we keep going back and forth to Myanmar, and it’s never been sustainable.”

Karim spoke of the conditions she returned to earlier this year in Cox’s Bazar, where aid cuts shut down healthcare facilities, and new arrivals were forced to share already overcrowded shelters. Her hope is for a stable and permanent repatriation of Rohingya refugees to the Rakhine state.

Despite the powerful statements from Rohingya leaders, some noted that no Rohingya who currently reside in the Cox’s Bazar camps were present at the Conference. Some officials cited logistical obstacles, but the Rohingya lamented that the voices of those within the camps were not heard.

Unanswered Questions and the International Community’s Role

There is much to be done for Rohingya refugees and those still living in Myanmar. Converging crises prevent effective solutions, and the wider conflict within the region overshadows the Rohingyas’ plight. The UN Conference put an international spotlight on the situation of forgotten people; however, few tangible commitments were made at the Conference. To relieve the suffering of the Rohingya, substantial action should be taken to prevent widespread atrocities by the Myanmar military, and the international community should materially invest in Rohingya development, education, and opportunities.