In the early history of democracies, political voting was inherently simple: it was the communication of approval or disapproval of policies, platforms, and so on. Dissention was normal, but the partisan politics we are familiar with today were almost nonexistent. Issues that one politician had with another’s proposal were addressed in a direct, timely manner. In terms of the general public, everyone was essentially getting the same information via the same means – the printed press. This meant everyone was getting the same information at the same time; there may have been differences in interpretations, but everyone was reading the same headline as their neighbor. Today, we have thousands of media vying for our attention on many topics, especially politics. Whether from CNN, MSNBC, NPR, or Fox News, we are bombarded with information on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and other social media.

So, how did we abruptly shift from getting news from the same medium to getting news from every angle? The answer is simple: The Internet. The Internet completely transformed how we receive and access all media of information, including political information; politicians can directly speak to voters who then participate in the political arena without leaving their home. Technological advancements in communication play an important role in influencing electoral behavior, easing the accessibility of political information. The Internet makes it easier to find out a candidate’s platform, what they want to work for, and their history. By using the internet in this way, people are engaging in what is now known as “digital citizenship.” A “digital citizen” is one who engages in democratic affairs in conventional ways by using an unconventional medium such as their laptop or smartphone.

The media’s role in elections and politics has grown exponentially since the 1960s. Prior to television, presidential candidates relied on the radio, think of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s fireside chats, and other interpersonal means to communicate with voters: caucuses, party conventions, town halls, and so on. As technology progressed and television became widely accessible, reliance on interpersonal connections diminished and reliance upon the media grew. Power transitioned from party leaders and bosses to the candidates – as they were able to take control of their campaign, so long as their actions were worthy enough to make headlines. This transfer of power once benefitted only the candidates; however, now the power resides with the media: for they decide what suits their audiences, and who America sees.

This transfer of power greatly impacts our political processes. When politicians are their own bosses, they are able to disregard societal “norms” and use populist rhetoric to enhance their performance in the political realm. Kellener asserts President Trump is the “master of media spectacle”; using populism to make headlines and instill fear into voters more susceptible to fear- and anger-based messaging, he was able to “use the disturbing underside of American politics to mobilize his supporters”.

The Good

ISTE.org layers the ‘digital’ components onto the definition of a conventional good citizen:

| A good citizen… | A good digital citizen… |

| Advocates for equal human rights for all | Advocates for equal digital rights for all |

| Treats others with respect | Seeks to understand all perspectives |

|

Does not steal or damage others’ property |

Respects digital privacy, intellectual property, and other rights of people online |

| Communicates clearly, respectfully, and with empathy | Communicates and acts with empathy for others’ humanity via digital channels |

| Speaks honestly and does not repeat unsubstantiated rumors | Applies critical thinking to all online sources, including fake news or advertisements |

| Works to make the world a better place | Leverages technology to advocate for and advance social causes |

| Protects self and others from harm | Is mindful of physical, emotional, and mental health while using digital tools |

| Teams up with others on community projects | Leverages digital tools to collaborate with others |

| Projects a positive self-image | Understands the permanence of the digital world and proactively manages digital identity |

All of the characteristics of a “good digital citizen” may be applied to participating in democracy via the Internet. If everyone had access to the internet, more people would be able to register to vote as well as discussing and engaging in the political arena. If we seek to understand more perspectives, we could combat the political “bubbles” that we either choose to live in or are placed into by Facebook filtering your newsfeed depending on your online habits. If we used technology to advocate for social causes such as voter disenfranchisement, we could get more people engaged with our democracy.

Being a “good” digital citizen transcends holding personal values – it includes the pursuit of equality for all. We are lucky enough to live in a country where digital citizenship is accessible for most, but we are doing no justice by those who cannot access it by not utilizing this new form of citizenship.

The Bad

The era of digital citizenship is a result of the rapid spread in access to the Internet. If you have access to the Internet in America, you have the opportunity to register to vote (given that you meet the proper requirements set by your state), to research political platforms and to engage with others to discuss politics. Political participation (not exclusive to voting) has increased – people are engaging more in more discussions on every form of media; however, these discussions may not always be beneficial or productive. Kurst says, due to our emotionally charged atmosphere in the US, it is very easy (and very typical) for conversations surrounding politics escalate to attacks on opposing values. It is easy to rely strictly on what you are told from your favorite news source or directly from a politician and regurgitate the rhetoric, but it is vital to our unity as a society to fact check your information, and respectfully listen to the “other side.”

In today’s political climate, virtually everything is politicized – including our social media. We live in our “red bubbles” or “blue bubbles” and disassociate from anyone who may be on the other side. Thompson argues this is normal; we seek homogeneity in our marriages, workplaces, neighborhoods, and peer groups. However, when it comes to politics and the Internet, we are allowed to pretend like those without similar interests do not exist. When we ostracize a group of people and those people feel as though they are not being represented, we see members of the Republican party proclaiming they are the “silent majority,” which was a galvanizing force behind their voter turnout in 2016. By devaluing another side’s beliefs, we are dehumanizing those who hold them. This causes anger, frustration, and retaliation – all of which that may take place in the digital or physical realms. We cannot abandon our fellow Americans simply because we disagree; we have to realize the differences we have are much less than the commonalities we share.

The polarization of the two parties in America today discredits many media outlets. 47% of conservatives said they get their news exclusively from Fox News; while liberals get theirs from a more diverse set of news. Conservatives and liberals alike see anything that does not reflect their values as “biased”, in fact, members of society gravitate to information that reaffirms their beliefs and intentionally avoid information that contradicts said beliefs, according to Drs. Rouhana and Bar-Tal. This creates a biased interpretation of the news – information that is consistent with already-held beliefs are interpreted as fact and support for whichever side of the argument the reader/viewer ascribes to. As a result, Americans question the validity of news sources that contradict that of their personal beliefs. The crossroads of political polarization and declining trust in our media outlets is where fake news exists. Truth has become a relative term and is often manipulated by an ideology, not fact.

How can we fix the political polarization tearing at the social fabric of American society? Establishing trust “across the aisle” seems like a hopeless cause in today’s America. When asked how to “pop” the political bubbles we live in, Gerson claims, “[the] cause is not hopeless, because the power of words to shape the human spirit is undeniable. These can be words that belittle, diminish and deceive. Or they can ring down the ages about human dignity. They can also allow us, for a moment, to enter the experiences of others and widen, just a bit, the aperture of our understanding. On the success of this calling much else depends.” The solution to diminishing this polarization is to listen – listen and realize the other person you are disagreeing with possess the same humanity you do, and this humanity should be respected.

Digital Citizenship and Human Rights

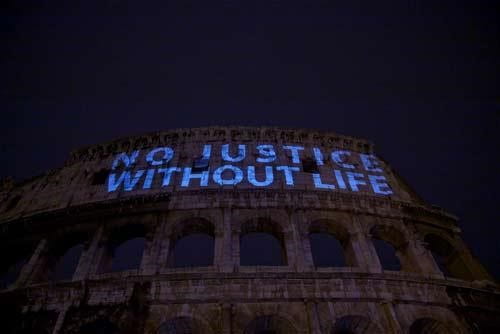

Marginalized populations have always struggled to get their voices heard. Without active engagement in democracy, minorities struggle to achieve full citizenship. The Internet and digital citizenship have worked together to diminish this obstacle faced by minorities. Social movements such as Black Lives Matter, #MeToo, and even the Arab Spring began and spread with the assistance of the Internet. Digital citizenship is linked to creating online communities to which people who struggle “fitting in” with their physical environment can find a home.

Using the Internet, citizens are easily mobilized on issues that concern them, whether domestic or international. They are able to pressure politicians to take actions against human rights violations and assist organizations doing field work where an injustice is present. For example, we are able to donate financially to the organizations making an effort to abolish the attacks on the LGBTQ+ community currently taking place in Chechnya, Russia. By being aware of it and all the other injustices taking place, we are able to assist in the resistance and make a difference in a way we could not have 10 years ago thanks to the Internet.

There are those who choose to not engage in politics in any shape or form, and there are those who use the Internet exclusively for political reasons. Wherever you fall within that spectrum, it is easy to agree that the polarization we have in America today is an issue that needs proper attention. It starts at the individual level: listening to what others who are different have to say, diversifying your news sources, and being open to disagreement. We must break out of our “bubbles” and not allow the influence of the Internet to shape our values for us.