Laws and policies not only reflect policy-makers’ knowledge about cultural norms but laws and policies also actively shape our cultural norms as well (Benabou & Tirole, 2011). Inclusive laws and policies may negate the reinforcement of discrimination of marginalized groups by changing attitudes towards said groups over time. This is especially true of the disability community. Prior to the enactment of inclusive policies, persons with disabilities could be legally and explicitly discriminated against in the fields of education, medicine, and employment. Persons with disabilities still face discrimination, but the following laws make strides toward shaping the United States into a more inclusive for persons with disabilities, and these laws have played a key role in shaping cultural norms regarding these issues.

Civil and political rights are protected by many different laws for all Americans; however, key pieces of legislation pertain specifically to persons with disabilities. Currently, three major federal laws protect persons with disabilities in the United States: the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) of 1975, and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990. Additionally, the United Nations also has implemented the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), an international commitment to promote accessibility on the global scale.

The Rehabilitation Act of 1973

The Rehabilitation Act was the first piece of civil rights legislation to explicitly identify the rights of persons with disabilities and outlaws the discrimination on the basis of disability in Federally-funded programs. This includes barring programs conducted by Federal agencies, programs receiving Federal financial assistance, and Federal employment from discriminating against persons with disabilities.

The Rehabilitation Act also:

- Defines persons with disabilities as those who have a physical or mental impairment that limits a major life activity, such as walking, seeing, hearing, speaking, learning, or working.

- Gives students with disabilities the right to appropriate education.

- ‘appropriate education’ is defined in this context as education that meets the unique educational needs of a student.

- Requires parents must be notified if their children are tested for learning difficulties, are identified as having a disability, or placed into special education programs. Parents are also given the option to object to their child’s evaluation results through a formal, impartial hearing.

- Mandates students with disabilities should be educated with their non-disabled peers when appropriate.

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)

The IDEA requires children with disabilities receive a free and appropriate education in the least restrictive environment appropriate to their individual needs and provides financial incentives for public education institutions complying with federal disability laws. IDEA also requires the implementation of Individualized Education Programs (IEP’s) for each child. These programs are developed by a team of individuals knowledgeable about the child’s situation (typically the child’s teacher, the parents, the child, and oftentimes an agency representative who is qualified to provide special education) and are required to be reviewed annually.

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act also:

- Protects children (up to age 21) deemed eligible for special education services.

- Allocates funds assisting states and other education agencies to meet special education requirements.

- Requires children in special education programs have a written IEP.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)

The ADA prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability in employment, state and local government, public accommodations, commercial facilities, transportation, and telecommunications and also applies to the United States Congress.

The Americans with Disabilities Act also:

- Prohibits explicit discrimination in recruitment, hiring, promotions, training, pay, social activities, and other privileges of employment and restricts questions that can be asked about an applicant’s disability before a job offer is made for employers who possess more than 15 employees.

- Requires employers “make reasonable accommodations to the known physical or mental limitations of otherwise qualified individuals with disabilities, unless it results in undue hardship”(29 CFR Parts 1630, 1602 (Title I, EEOC)).

- Requires state and local governments follow specific architectural guidelines in the new construction and alteration of their buildings.

- Provides a telephone hotline if disability-related complaints need to be filed. These complaints are filed with the Department of Justice, who may provide mediation programs if necessary.

- Requires all public transportation services (such as city buses and public rail transit) are fully accessible.

- Requires common carriers establish interstate and intrastate telecommunication relay services 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

- Requires closed captioning of federally-funded public service announcements.

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD)

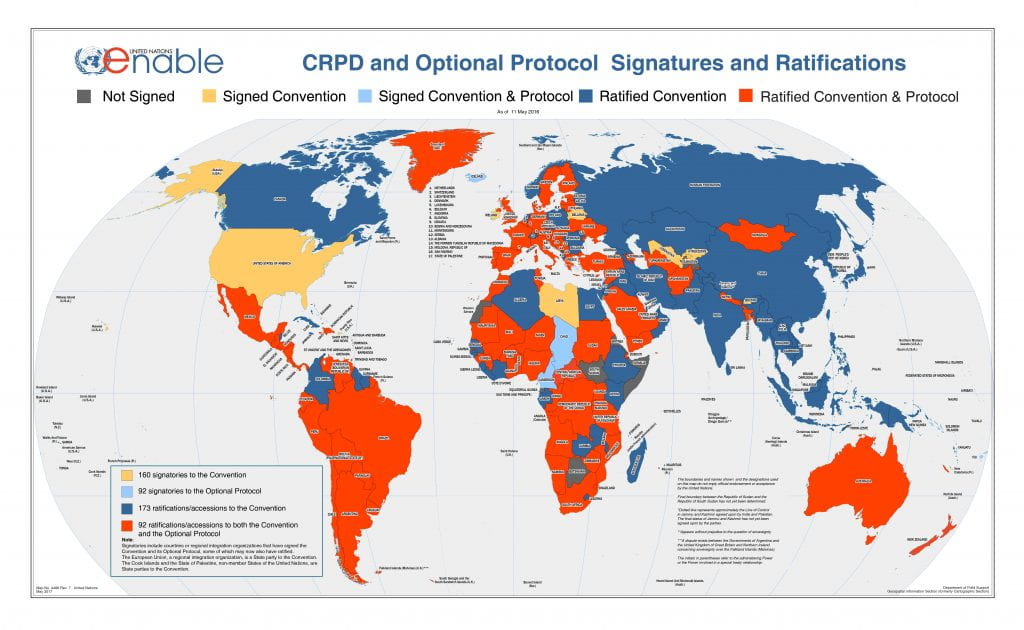

The CRPD and its Optional Protocol were adopted by the United Nations in 2006. With 82 signatories to the Convention, 44 signatories to the Optional Protocol, and 1 ratification to the Convention, the CRPD has the highest number of signatories in history to a United Nations Convention. It is also the first legally binding, international treaty protecting the rights of persons with disabilities. The CRPD is the first human rights treaty of the 21st century and is the first to allow both regional economic integration organizations and civil society are parties to negotiations of a Convention. The UN defines the CRPD as “a human rights instrument with an explicit, social development“. This document reaffirms persons with disabilities (not restricted to physical and/or visible disabilities) must enjoy all fundamental freedoms and human rights.

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities also:

- Is the fastest growing treaty in the history of the UN.

- Embraces a human rights-based approach (HRBA) of disability. HRBA shifted the approach to disability from “objects” of charity, social protection, and medical treatment towards a doctrine of human rights, envisioning persons with disabilities should make their own decisions about life, the future, and claim rights on their own behalf.

- Defines disability as an evolving and open concept.

- Encourages the participation of civil society, particularly persons with disabilities and their related organizations. This follows the Convention’s slogan, “Nothing about us without us.”

- Protects persons with disabilities from direct and indirect discrimination and provides reporting mechanisms if a person’s rights are violated within the context of the CRPD.

Why Disability Laws and Policies are Needed

There are more than 1 billion people in the world are currently living with a disability; about 59.7 million of them live within the United States. Batavia (2001) asserts civil rights legislation, such as those aforementioned, open doors for persons with disabilities that were otherwise sealed shut while also normalizing persons with disabilities in the workplace and beyond. It is apparent that such legislation has moved the United States and the world toward a more inclusive and accessible world, but there is still work to be done. Batavia (2001) points out less than 20% of complaints filed under the ADA end up ruling in favor of the defendant. This is the typical average for complaints filed under anti-discrimination laws in the United States; however, Batavia also argues the percentage for the ADA specifically should be much higher due to the uniqueness of each individual disability and necessary accommodations for them. Society oftentimes reinforces views of persons with disabilities as a ‘burden’ or ‘incapable’; one way to break these negative stigmatizations is via policy and respecting those policies as citizens.

If laws are changed, then public opinion toward a particular subject may change along with it. However, this change takes time; when sodomy was decriminalized in the United States in the 1950s, public opinion on same-sex and other queer couples began to shift. The shift over time pressured the Supreme Court to rule in favor of Queer Rights when same-sex couples gained the right to marry in 2015. The LGBTQ+ community still faces many obstacles today, but they are substantially less than those faced before favorable legislation was passed. Without a tireless effort, laws such as the ADA or the CRPD may have taken a much longer time to manifest. These efforts must continue in order to eradicate the stigma surrounding persons with disabilities.

References:

Batavia, Andrew I., and Kay Schriner. “The Americans with Disabilities Act as Engine of Social

Change: Models of Disability and the Potential of a Civil Rights Approach.” Policy

Studies Journal 29.4 (2001): 690-702.

Benabou, Roland, and Jean Tirole. Laws and Norms. No. w17579. National Bureau of

Economic Research, 2011.

Keep up with the latest announcements related to the upcoming Symposium on Disability Rights by following the IHR on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.