by James DeLano

Historical Slavery in the United States

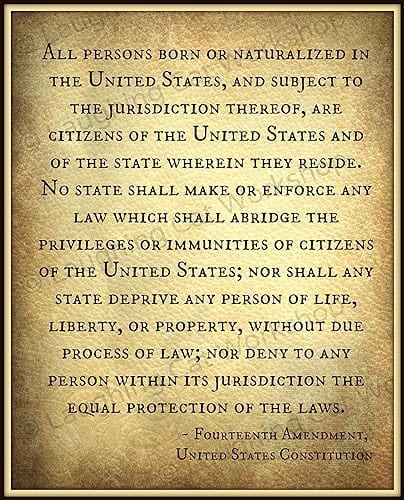

Slavery was abolished in the United States in 1865 with the ratification of the 13th Amendment. The amendment reads, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

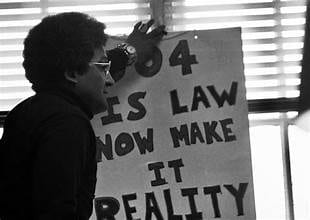

At least, that is what I was taught in high school: slavery ended in 1865 with the 13th Amendment. What was not taught was the century and a half of forced labor since then, predicated on an intentional loophole in the 13th Amendment. Activists were active in their denouncement of and work towards ending this system over a century ago, and not much has changed since.

That loophole was not the only way slavery persisted. Chattel slavery, slavery as it existed in the South prior to 1865, existed in the United States until at least 1963. Mae Louise Walls Miller grew up in rural Louisiana, where she and her family were enslaved. They were freed in 1963, when she was only 14 years old. Her family, possibly the last chattel slaves in the United States, were freed after President Biden graduated high school. This was not an isolated instance; this form of slavery existed in scattered patches across the rural South for decades after the end of the Civil War.

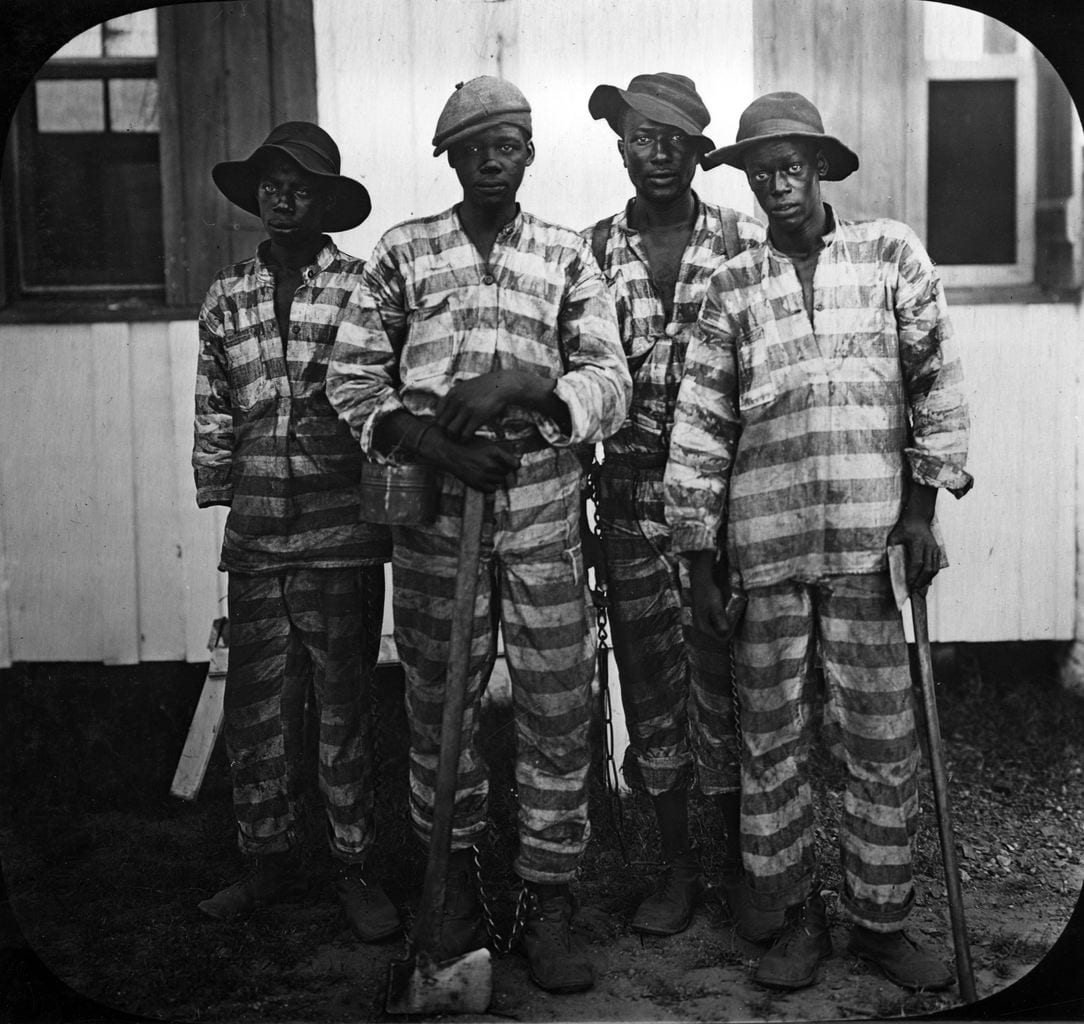

In this post, I will illustrate how forced prison labor continues to maintain slavery in the United States.The convict leasing system, where people convicted of crimes are “leased” to companies to perform hard labor, started in Alabama in 1846, and their prevalence exploded after the 13th Amendment abolished what was previously the most common form of forced labor. This system was incredibly dangerous; in 1874, a typical death rate was one-third of people working on railroads. A contemporary prison official said that “if tombstones were erected over the graves of all the convicts who fell either by the bullet of the overseer or his guards during the construction of one of the railroads, it would be one continuous graveyard from one end to the other.” Elsewhere, between 1888 and 1896, over 400 people died of tuberculosis contracted while working in Sloss Steel and Iron Company mines.

Many of those arrested and convicted during this system were sentenced under questionable circumstances. One common situation was being arrested for riding a train without a ticket “by a man who is paid $2 for every person he arrests upon that charge.” After accounting for inflation, $2 in 1907 would be worth over $65 today.

Between 1880 and 1900, this system profited over $1,134,107 in saved labor costs, which would be worth nearly $40,000,000 today. It profited $1,322,279 between 1900 and 1906. Alabama banned this method of forced labor in 1928.

Modern American Slavery

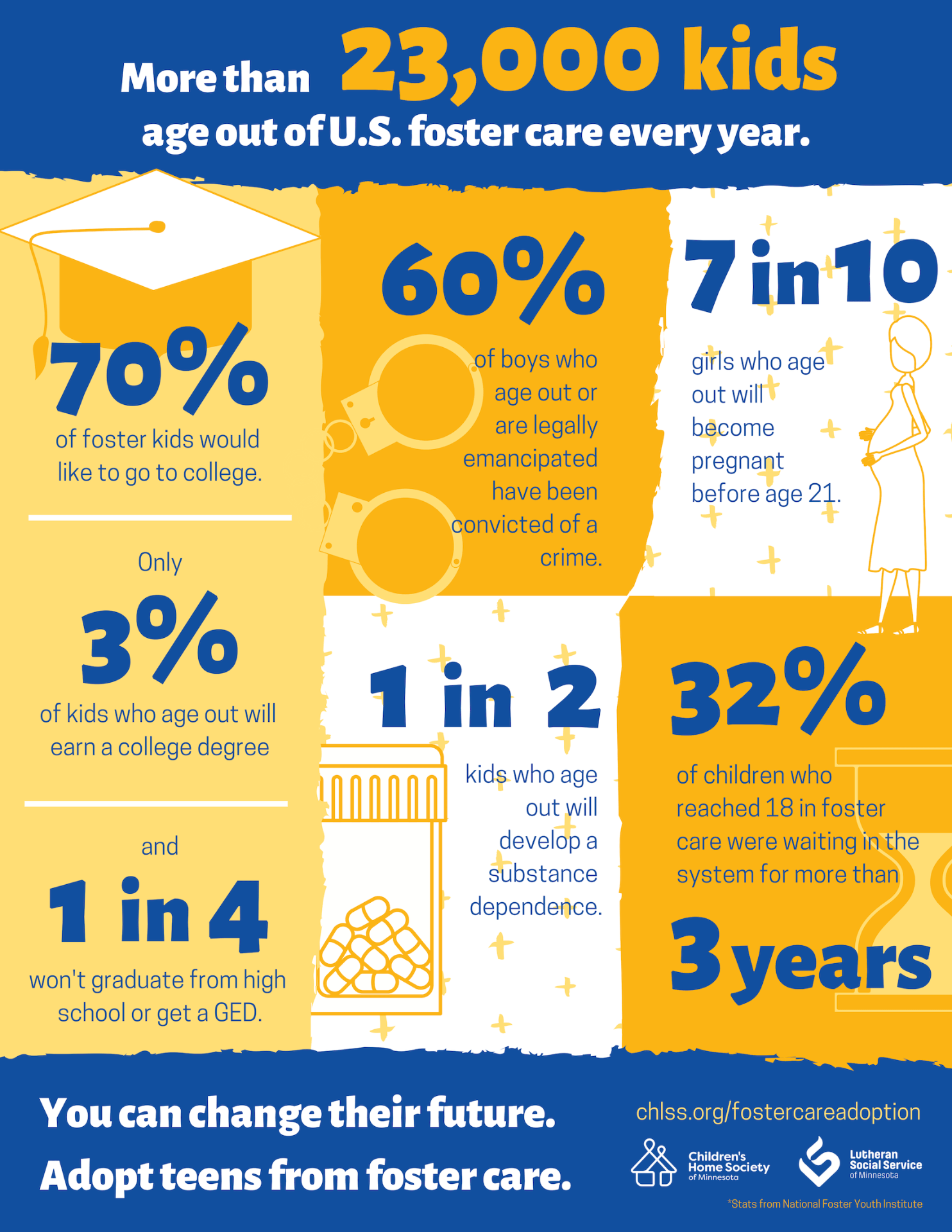

The United States has maintained both the highest incarceration rate of any country in the world and the highest prison population for several years. Two-thirds of inmates in American prisons are also workers in both private-sector and public-sector jobs. Alabama convicts on work-release programs are allegedly paid just over $2 per day.

Alabama did not stop using forced prison labor in 1928. A lawsuit was filed in December 2023 alleging gross mistreatment, violations of both the United States and Alabama Constitutions, and instances of retaliation against a convict on work-release due to reporting of sexual harassment. It alleges dangerous working conditions; in August, two convicts were killed while working as part of a road crew. It alleges the intentional violation of parole guidelines in order to continue the system of forced labor as it currently exists in prisons. It also repeats accusations of negligence in regard to healthcare. Antonio Arez Smith was released last year in “excruciating pain” due to untreated cancer. He died four days after his release. The Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC) stopped releasing inmate death statistics in October after years of increasing rates.

According to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), 64% of incarcerated people being forced to work felt unsafe while doing so, and 70% did not receive job training. None of what I have mentioned above is considered enough of a crime to warrant consequences.

Workers’ protections do not apply to incarcerated people, including minimum wage laws, unionization, and any assurance of workplace safety. None of this should be surprising knowing the text of the 13th Amendment; incarceration is explicitly listed as an exception to the abolishment of slavery, and slaves are not permitted rights.

This form of forced labor is ubiquitous. The lawsuit previously mentioned lists as defendants companies that have become household names: McDonald’s and the parent companies of Wendy’s, KFC, and Burger King. Elsewhere, well-known companies use prison labor as a cost-cutting measure: Amazon, AT&T, Home Depot, FedEx, Lockheed-Martin, and Coca-Cola, as well as thousands more nationwide.

The Alabama Department of Corrections reported generating over $48,000,000 in 2021, and received hundreds of millions of dollars more from other sources. Most of that was directly appropriated from the state, but it also included federal funding intended for COVID relief. The total sum diverted into the Department of Corrections was $400,000,000, or about one-fifth of the total relief funds. The Treasury Department describes the funds as “support[ing] families and businesses struggling with [the pandemic’s] public health and economic impacts.” Instead of spending it on struggling Alabamians and small Alabama businesses, the state spent its funds on building new prisons despite us already having one of the highest incarceration rates in the country.

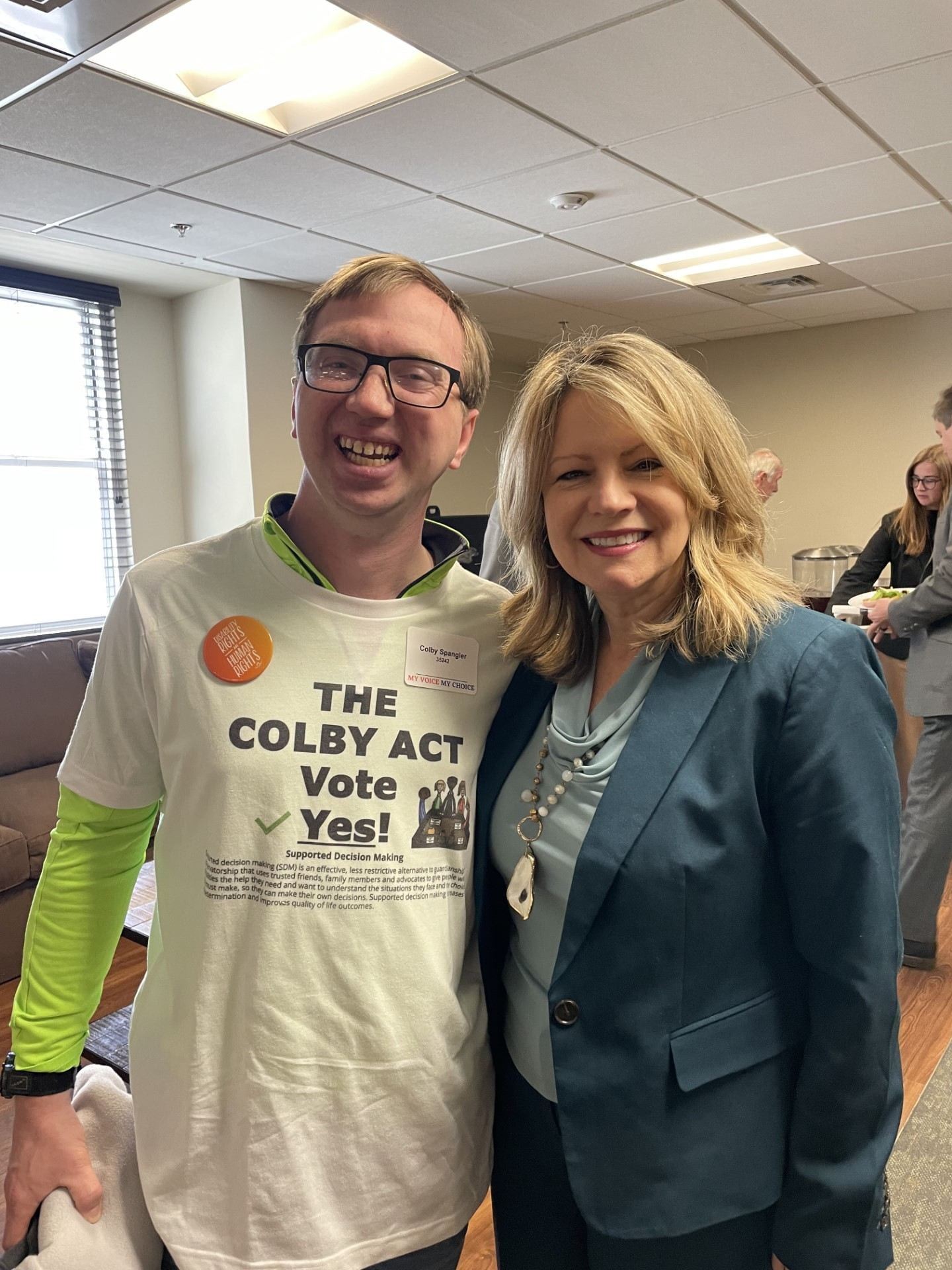

What is Being Done

The Alabama Department of Corrections is involved in several lawsuits related to alleged misconduct. The aforementioned lawsuit, Council v. Ivey, has a hearing scheduled for February 8th. ADOC is involved in several other lawsuits and has been for decades; Braggs v. Dunn was filed in late 2014 over neglect and remains unresolved, as does a Department of Justice lawsuit filed in late 2020 over critical understaffing. The new Alabama constitution, voted on in 2022, changed the text’s phrasing of its prohibition of slavery. Prior to that vote, it read, “no form of slavery shall exist in this State; and there shall not be any involuntary servitude, otherwise than for the punishment of crime, of which the party shall have been duly convicted.” The equivalent section now reads “That no form of slavery shall exist in this state; and there shall not be any involuntary servitude.” In addition, Congresswoman Nikema Williams and Senators Jeff Merkley and Cory Booker have proposed the federal “Abolition Amendment,” intended to close the prison labor loophole.

Nationally, prison reform is a coordinated movement. Numerous organizations focusing on prison reform generally also have efforts in place to reform or abolish forced prison labor. I have used sources from the Equal Justice Initiative and the American Civil Liberties Union in this piece. The lawsuits mentioned were filed by current and former Alabama inmates, the Southern Poverty Law Center and Alabama Disability Advocacy Program, and the U.S. Department of Justice. Of those, only Council v. Ivey directly addresses forced labor; the others work towards improving prison conditions more broadly but still contribute to the common goal of reforming prisons.