Content warning: this blog will include mentions of child abuse, child self-harm, child suicide, and child sexual abuse.

Psychiatric Residential Treatment Facilities (PRTFs) are in-patient institutions that provide inpatient psychiatric care to people under the age of 21. They are a common form of short-term psychiatric care for young people. Children do not choose to be committed to these facilities, and they do not want to be. Two children said they were being treated like animals. Many said, “I don’t feel safe.”

Physical Abuse

Children in PRTFs are extremely vulnerable due to both psychiatric issues and the nature of living in institutionalized care. Facilities are often understaffed, leading to minimal supervision and increased opportunities for abuse – by staff and other children.

Staff members at PRTFs have frequent opportunities to abuse their charges. A staff member at Cumberland Hospital in Virginia “poured scalding water on a non-verbal 16-year-old.” An 11-year-old boy from Arkansas was pushed down, had his hair pulled, and had a staff member place her foot in his back. A staff member at Devereaux Brandywine in Pennsylvania was found guilty of assault after she “punched and kicked a 14-year-old in the head, face, and body until the child was unconscious.” In December 2023, a staff member at a facility in Arkansas told a police officer, “I went in there, and I basically twisted his ear real hard in order to get him off the bed, which we’re not supposed to touch them.” A staffer at a facility in South Carolina “hit the child twice, including punching the child in the head.” At a Devereux facility in Viera, Florida, a staff member hit a boy on his neck, leaving marks. It is sad that state governments pay pay thousands of dollars daily for children to be abused by their caretakers.

Further, due to apathy and unawareness from staff, children are also able to abuse other children in PRTFs. At Riverside Hospital in Virginia, a child was “repeatedly stabbed by another child.” At North Star Behavioral Health in Alaska, after two children were accidentally placed in seclusion together, one child gave the other a bloody nose. At the same Alaska facility, a child was “punched, slapped in the eye, and kicked by other children.”

None of these instances of abuse were reported to the children’s guardians in a timely manner. Some parents were never notified.

Sexual Abuse

A caregiver at Lighthouse Care Center of Augusta, in Augusta, Georgia, was arrested and convicted of child molestation. An employee at a facility in Alabama was sentenced after sexually abusing a 13-year-old boy she should have been caring for. A man working at a facility in Chicago was charged with three counts after sexually assaulting minors in his care. A Utah man pled guilty to sexually abusing three male students at a residential school he worked at.

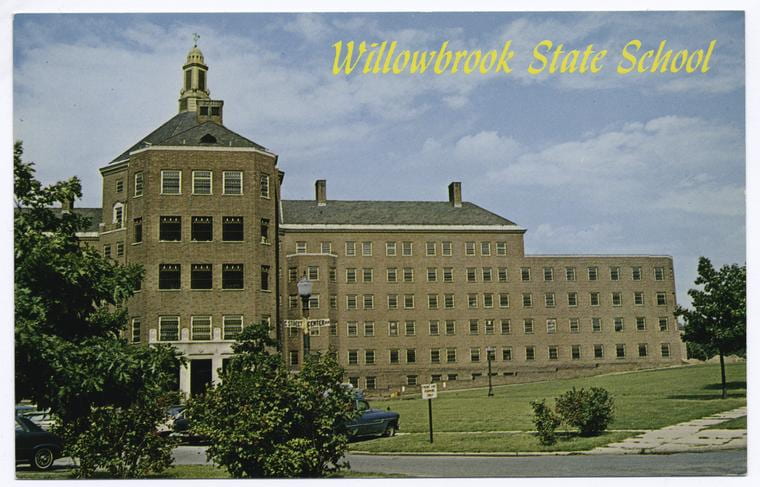

Staff members also allow sexual abuse to occur between children. At Devereux Brandywine in Pennsylvania, a 13-year-old boy asked not to be placed in a room with an older boy he was afraid of. They were placed as roommates, and “the older boy forced the younger child to perform oral sex on him on three successive nights in a walk-in closet.” This is one of many equally disturbing instances of staff enabling sexual abuse at facilities. One facility in New Mexico closed partially due to “the unchecked spread of HIV among patients” – something that brings to mind the hepatitis experiments of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s at Willowbrook State School, an infamous institution in New York.

Neglect and Unsafe Environments

Staff at PRTFs are often unable or unwilling to prevent children from harming themselves. Disability Rights Arkansas, the Protection & Advocacy Agency for Arkansas, reported that one girl “still had access to items to cut her arms. There were numerous new scars over her old scars.” The staff did not care. Another child at the same facility said that she had “used the second stall [with cracked and sharp shower tiles] to self-harm.” The staff did not care. If they had, the children in their care would be safe. A child at Palmetto Pines Behavioral Health in South Carolina “barricaded themselves inside of his suicide watch room…[and] used the plastics piece to cut his neck in an attempt to kill himself, but it was not sharp enough.” The staff did not care. A child at Provo Canyon School in Utah “caused personal injury during self-harm, with wounds that were one and two inches in length… through the fatty tissue.” At Oak Plains Academy in Tennessee, two 15-year-olds overdosed on Benadryl. The mother of one of them said, “I’ll never see her again; I just want justice for her; I just want her story told. And I want – I never want this to happen again to anyone.”

Minority Children

Children who are also members of minoritized groups, especially children of color and LGBTQIA+ children, have even greater difficulties in PRTFs.

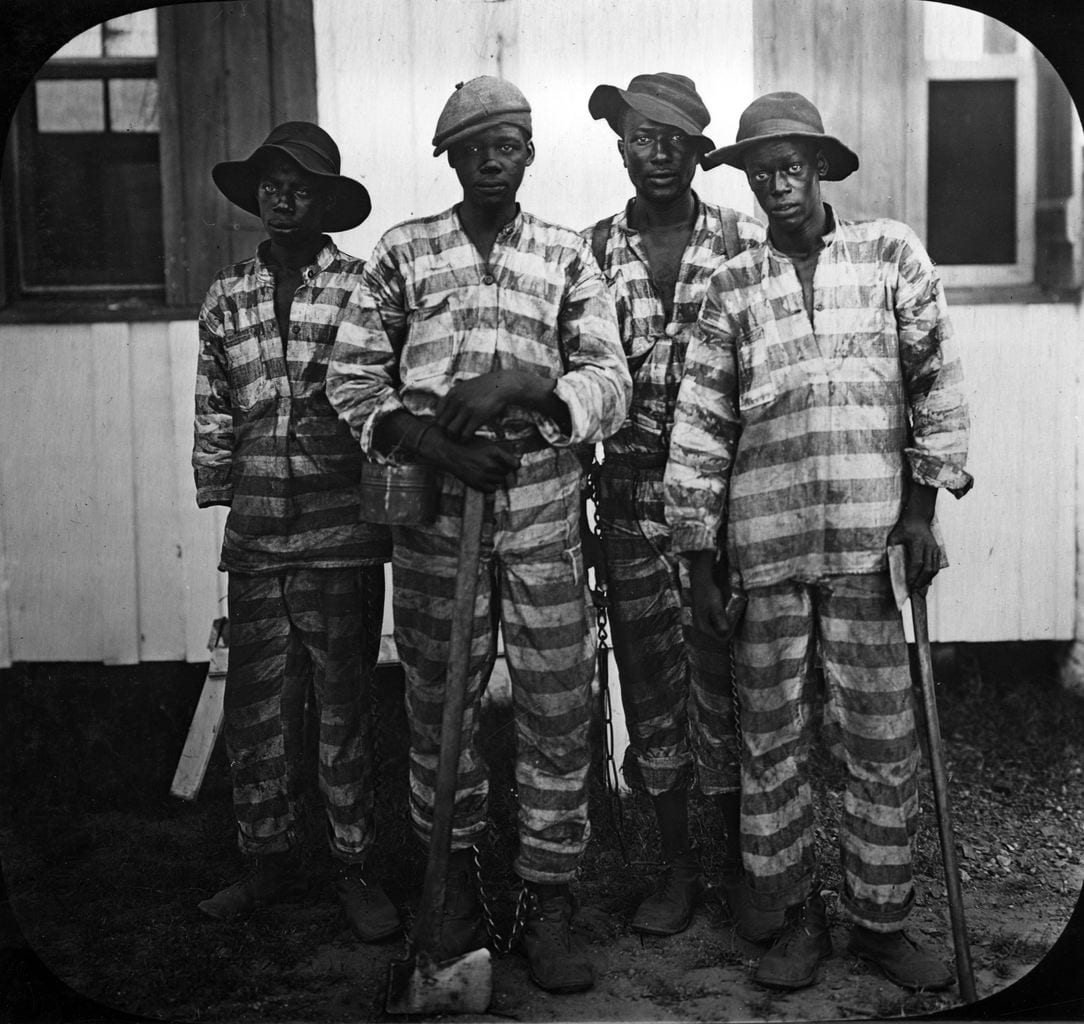

According to a Senate report, “[T]he longer an RTF stay, the longer a child is at risk of exposure to harms, including the use of restraints and seclusion, physical and sexual abuse, insufficient education, and substandard living conditions. This risk is heightened for children of color, LGBTQIA+ youth, and children with I/DD (intellectual/developmental disabilities) who are most likely to live in these settings.” Black children are 35% more likely than white children to be placed in institutionalized care facilities.

Cornelius Frederick, a 16-year-old Black boy from Michigan, was killed at a facility in Kalamazoo, Michigan, in April 2020. Seven male staff members restrained Frederick for 12 minutes. The medical examiner ruled his death a homicide – asphyxiation.

In 2018, a gay 16-year-old was attacked while residing at St. John’s Academy, a Sequel facility in Florida. His attacker told him that he “didn’t want a fa***t in the pod.” Disability Rights Washington reported that two “crisis plans” for children residing at PRTFs used incorrect gendered pronouns when referring to the child. In 2020, two transgender girls resided at Sequel Courtland in Courtland, Alabama – a boys’ facility. One girl was being stalked by other residents. She did not feel safe.

Further Information

For further reading about the kinds of abuses that go on in these facilities, consider reading a blog I wrote in April about group homes. You can also reach out to local representatives about ending or reducing out-of-state institutionalizations, which are harder to investigate than in-state institutions.