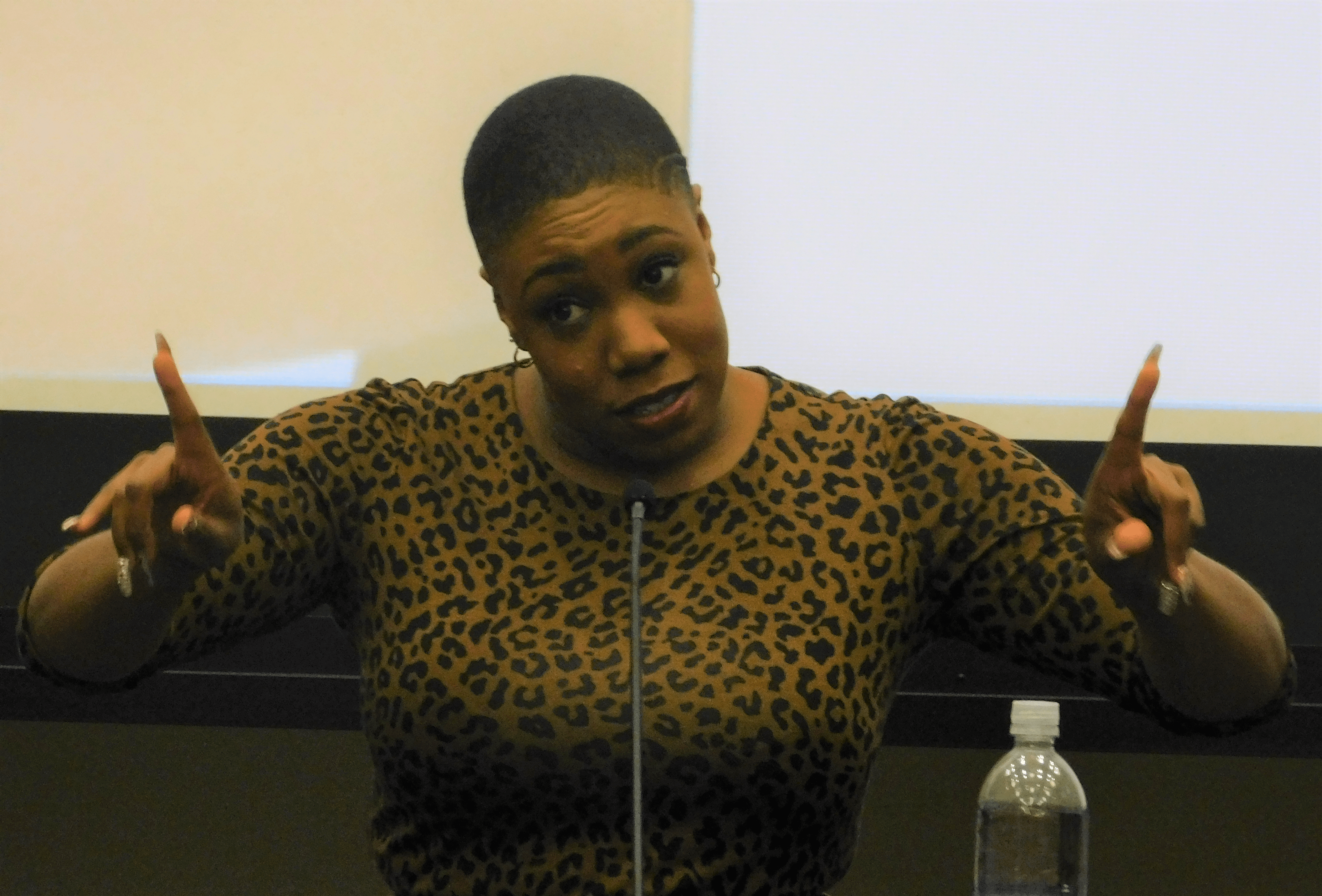

On Wednesday, March 20th, the Institute for Human Rights co-sponsored the UAB Lecture Series alongside Undergraduate Student Government, Graduate Student Government, Student Involvement & Leadership, and Leadership and Service Council to present political strategist and commentator Symone Sanders.

Sanders began by critiquing the cliché of how one would change the world if they had a magic wand. However, in this world, she insisted we’ll never have that opportunity because social change doesn’t operate through a blank slate. As a result, we must work with a system that doesn’t want to change which warrants radical revolutionary leadership in the spirit of community.

This evoked Sanders to propose her tenants for being a radical revolutionary:

- First, you must be willing to buck the status quo and take a risk.

- Second, you must be willing to feel uncomfortable and act.

- Third, you must be willing to stand in the gap for other people.

- Fourth, you must be willing to take on your adversaries as well as your allies.

- Finally, you must pick an issue and care about it.

Sanders admitted these tenants were inspired by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s commitment to social change by claiming that immediately after his assassination, many Americans blamed him for his own demise because they believed he was doing too much. In contrast, Dr. King’s current legacy of racial and economic justice is well-respected. Sanders insisted Dr. King was often very uncomfortable when addressing injustice across the country and implored the audience to be more like him when it comes to strategic community building, namely when it comes to intersectional and intergenerational coalitions. As for challenging your allies, Sanders admitted that she recently had to condemn the sexual assault allegations against her friend and Virginia Lt. Governor Justin Fairfax because truth is truth and much like Dr. King, “…silence is betrayal”. She claimed radical revolutionaries are vigilant about what’s happening to marginalized communities across the country and allow themselves to hope, dream, and have an outline for social change.

Amid political and social turmoil nationwide, Sanders’ lecture about becoming a radical revolutionary is timely as well as necessary. By modeling this approach from Dr. King’s legacy, Sanders has drafted a pragmatic, although challenging, formula that has and will continue to confront injustices that have outstayed their welcome in U.S. culture. Sanders largely addressed the challenges of race and sex-based discrimination, not only in the political area but in her personal life, who as a Black woman must constantly confront intersectioning prejudices that attempt, but fail, to undermine her Black womanhood.

Sanders said to the crowd, which was predominantly UAB students, there is no one more powerful in the world than young people in U.S. and that we must be willing to do things that have never been done before. This claim is particularly salient to a group of people that were likely ineligible to vote in the most recent U.S. presidential election. For this reason, these young, aspiring minds are capable of taking this narrative to their families, friends, classmates, and the voting polls which can embolden the revolutionary change our society needs and deserves.