One of the crowning achievements of the Civil Rights Movement was the passage of the Voting Rights Act. Signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1965, the Voting Rights Act deemed state and federal tactics designed to restrict African Americans from exercising their right to vote unconstitutional. This made voter suppression efforts such as poll taxes and literacy tests illegal and required states and jurisdictions with a history of voter suppression and discrimination to obtain pre-clearance from the federal government before implementing any changes to voting laws or election practices. In 2013, citizens of Shelby County, Alabama, sued Attorney General Eric Holder, citing that sections of the 1965 Voting Rights Act were no longer necessary because discrimination in voting was no longer a problem. In a 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs. This decision has the power to single-handedly unhinge the electoral process in America.

1965 Voting Rights Act

Prior to the passage of the Voting Rights Act, minority voters were victims of vicious voter suppression tactics, and many lost their lives in the pursuit of an elusive constitutional right. These tactics included unaffordable poll taxes, frivolous literacy tests and harassment. Poll taxes financially penalized non-voters for every year they went unregistered to vote since the 1890s, a time when people of African descent were not legally allowed to vote. Literacy tests were designed to deter minority voters, many of whom were illiterate due to oppression and lack of educational opportunities. Women such as Amelia Boyton Robinson and Annie Lee Cooper attempted to register multiple times in the City of Selma, Alabama. These women and others were met with hostile opposition and fierce resistance from the state. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 enforced the 15th amendment of the United States Constitution and prohibited discriminatory voting practices such as literacy tests. It also empowered the federal government to take an active role in the oversight of voter registration and electoral processes in states that have a documented history of voter suppression and intimidation. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 explicitly prohibited the states of Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Virginia from making changes to voting procedure without the approval of the federal government. Following the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, voter registration increased drastically amongst minorities throughout the United States, especially in the South.

Shelby County v. Holder

On June 25, 2013, the Supreme Court of the United States of America made a monumental decision that has and will continue to have residual effects on the electoral process moving forward. Shelby County v. Holder, 570 U.S 529 (2013)directly challenged the legality of Section 4 of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Section 4 implemented a coverage formula that determined which voting districts were required to receive governmental pre-clearance. Pre-clearance is a term used to describe the role of the federal government in the voting process. Jurisdictions that were required by the 1965 Voting Rights Act to receive pre-clearance from the federal government were restricted from making any changes to voting laws without the pre-approval of the federal government. Prior to the pre-clearance clause, states that have long histories of voter suppression were allowed to make legal changes to the voting process with no opposition. The Supreme Court ruled that segments of Section 4 of the Voting Rights Act were unconstitutional and should no longer be implemented. The court ruled the restrictions placed on particular states years prior are no longer relevant and are now in violation of the state’s constitutional right to regulate elections. Chief Justice John Roberts stated in the opinion of the court, “Our country has changed, and while any racial discrimination in voting is too much, Congress must ensure that the legislation it passes to remedy that problem speaks to current conditions.” The court had the opportunity to reinforce The Voting Rights Act and instead decided to relegate the responsibility of protecting voting rights to Congress. This ruling greatly weakened the Voting Rights Act as a whole. Now, states such as Alabama, Mississippi, and Georgia are free to make changes to voting laws that are not explicitly covered under other sections of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Shelby County, Alabama successfully argued that states with a blatant history of racism and oppression were no longer in need of governmental oversight because “that was a long time ago” and these discriminatory practices had been discontinued. Following the Shelby County v. Holder decision of 2013, the state of Alabama began regressing advancements made since the passage of the Voting Rights Act. Alabama passed a “voter ID law, closed polling places in predominately Black counties, and purged hundreds of thousands of people from voter rolls.”

The Future of Voting

The true ramifications of Shelby County v. Holder are yet to be seen, but there have been slight and monumental changes to the election process thus far. Alabama now requires a valid photo ID, polling stations are closing for no apparent reason, and voting lines are unusually long. Voting remains elusive for minorities, and the United States still does not have free and fair elections. For example, the most recent gubernatorial election in the state of Georgia displayed instances of blatant voter suppression. Brian Kemp was serving as the Secretary of State for the state of Georgia while he was actively campaigning against Stacey Abrams for Governor. Georgia’s 2018 gubernatorial election was riddled with complaints filed by voters that citied instances of voter suppression at and around the polls. The most prominent complaint was that in 2017 then Secretary of State Brian Kemp’s office removed 560,000 Georgia voters from the state voter registration logs. Many of the voters that were purged from Georgia’s registration logs in 2017 were not made aware of this until they attempted to vote in the 2018 gubernatorial election. Prior to the decision rendered in Shelby County v. Holder, Brian Kemp would have been required by law to obtain pre-clearance from the federal government before purging these voters from Georgia’s voter registration logs. Without the protections of the federal government, state governments are free to alter the voting process with no consciences. The 2017 voter purge in Georgia is one of the more well-known instances of state exploitation of the Shelby County v. Holder decision in the name of voter suppression.

With a Heavy Heart

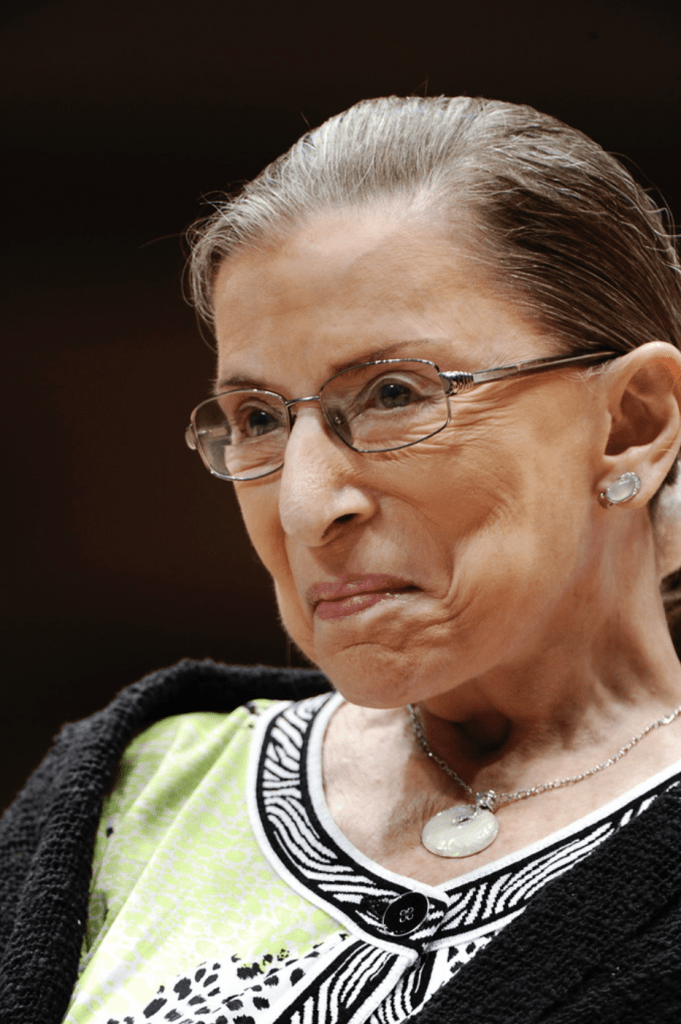

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg fought tirelessly for the protections of civil rights in America. A formidable champion of voting rights, she believed it is Court’s duty above all else to protect the right to vote and to protect the election process.Justice Ginsberg’s most notable dissent was in the Shelby County v. Holder decision. Justice Ginsberg’s stated in her dissent, “Throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.” Justice Ginsberg’s dissent in the Shelby County v. Holder decision can and will be citied in future legal documentation that directly challenges the decision rendered in Shelby County v. Holder. Ruth Bader Ginsberg’s dissent is indicative of the life that she lived. Justice Ginsberg was a champion of civil rights and she made a monumental impact.

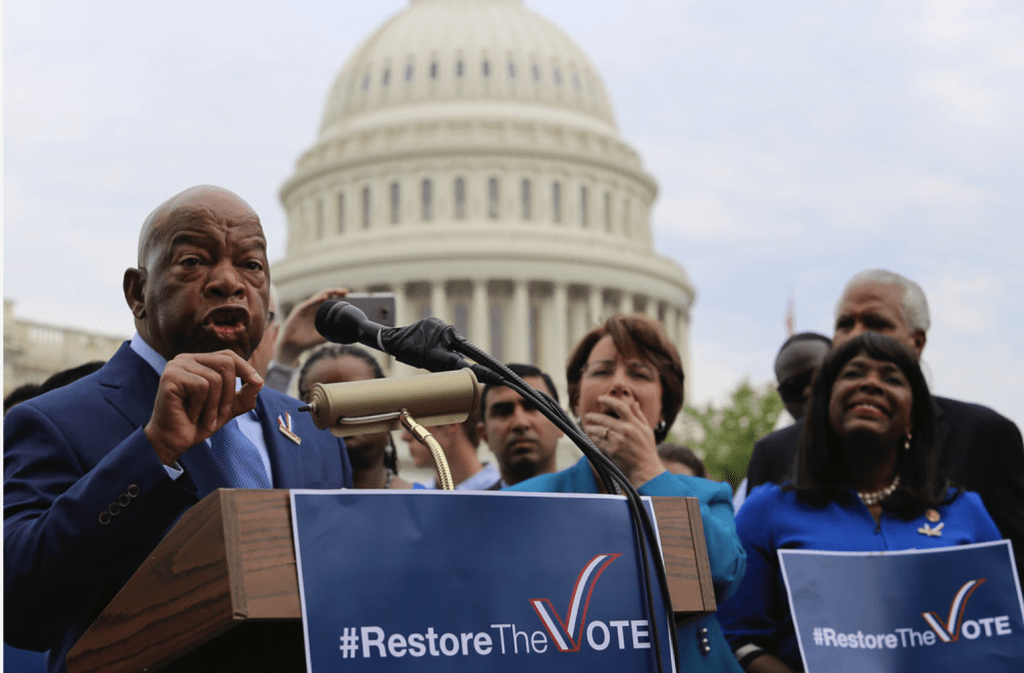

Call to Action

Voting is a fundamental right that should be guaranteed to all human beings of voting age. It is imperative that we understand the price of not voting and understand the importance of being politically aware and conscience of the decisions being made on our behalf without our knowledge. November 3, 2020 is quickly approaching and the need to vote is as important now as it has always been. The best way to amend the injustices made by the Supreme Court and elected officials is to elect individuals that will fight for justice and make voting easier for all citizens. The goal is to guarantee free and fair elections and to have an electoral system that prioritizes everyone equally and refuses to benefit from the marginalization of valuable perspectives and unique experiences.