*Cover Image Photo credits to Sharon Drummond*

Reading has always been one of my passions. It’s a unique entryway to view the world through another person’s eyes. Scientific research has shown that the more someone reads, the more empathetic and understanding that person is. It is these skills and values that reside at the core of human rights. To recognize the inherent dignity of every person, we must first be able to critically reflect on our own lives, positions, and privileges and grasp that our realities are not everyone’s.

To bring about a more caring, empathetic world, we need to learn to look beyond ourselves. Below are some authors whose pioneering work does just that.

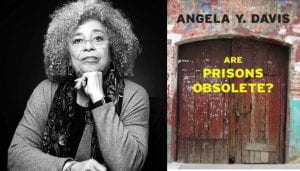

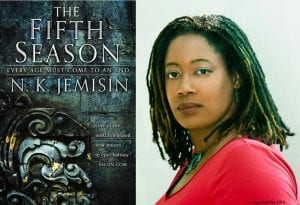

N.K. Jemisin

N.K. Jemisin is an author at the forefront of science fiction writing 一 in fact, she’s changing it at this moment.

Having been compared to greats in the genre like Arthur C. Clarke, Orson Scott Card, and Ursula K. Le Guin, Jemisin is one of the rare authors whose work has won not only the Hugo Science Fiction Writing Award but also the Nebula Award.

Only 25 books have won both the Hugo and Nebula awards, and Jemisin’s third novel in her Broken Earth trilogies is one.

Moreover, she is the first author in history to receive three consecutive Hugo Awards for every book within her critically acclaimed Broken Earth trilogy. The series is set in a broken world, literally, with a plot full of betrayals, murder, and a mother’s unbroken determination to save her daughter.

If you’re someone who loves science fiction, you need to read Jemisin’s works 一 one series in particular.

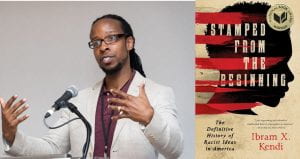

Ibram X. Kendi

Dr. Ibram X. Kendi is a name you should become familiar with if you’re interested in antiracist scholarship. As the author of 13 books for adults and children, he is one of the world’s leading historians and antiracist researchers.

Dr. Kendi is an Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities, teaching at prestigious institutions like Boston University and American University. He is also the Founding Director of the Boston University Center for Antiracist Research in the United States, while also being a contributor to The Atlantic and CBS News.

He authored the book Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America which won the National Book Award for Nonfiction, making him the youngest person in history to receive the award.

Alongside this book, he also published the internationally renowned How to Be an Antiracist. He has worked alongside other authors to make both critical works accessible to teenage and children audiences. As of 2021, he was awarded the MacArthur Fellowship, also known as the Genius Award.

Learn more about Dr. Kendi’s transformative research and start your own education into antiracism by checking out his site.

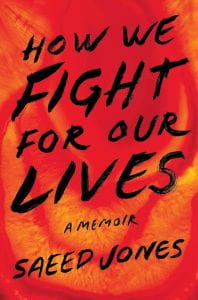

Saeed Jones

Saeed Jones is an award-winning poet and non-fiction writer. His poetry has won the 2015 PEN/Joyce Osterweil Award for Poetry and the 2015 Stonewall Book Award/Barbara Gittings Literature Award, as well as, a Lambda Literary Award.

His memoir, How We Fight for Our Lives, won the 2019 Kirkus Prize for Non-fiction. It is a poignant true story of Jones’ coming-of-age in a rural Texas community as a gay, black man.

Jones’s work is a sincere and heartbreaking presentation of the realities that Queer individuals reconcile with as they grow into their gender and sexual identities. Not to mention the added stigmas racial and ethnic minorities face.

If you’ve been wanting to break into the poetry scene or buff up on your memoir and/or Queer writing, you can find more of Saeed Jones’ work here.

Nicole Dennis-Benn

The work of Nicole Dennis-Benn has been compared to the pioneering and lyrical works of Toni Morrison. Her debut novel, Here Comes the Sun, was named the New York Time Book of the Year in 2016. Moreover, it earned the Lambda Literary Award for its portrayal Queer individuals.

Similarly, her second novel, Patsy, also received the Lambda Literary Award in 2020 and was a New York Times Editor’s Choice.

Nicole-Benn has taught at several writing programs at Princeton University, the University of Pennsylvania, NYU, and more. She is a recipient of the National Foundation for the Arts Grant and has published essays and shorter works in numerous esteemed publications 一 many of which have been nominated for or won awards as well.

She is the founder of the Stuyvesant Writing Workshop and currently lives in Brooklyn, NY with her two sons and wife.

Being born and raised in Kingston, Jamaica, her two novels are set in her home country. If you are someone looking to expand their reading beyond the borders of the U.S., check out the writings of Nicole Dennis-Ben.

Robert Jones, Jr.

Formerly known as “Son of Baldwin,” Jones’ debut novel, The Prophets, came into immediate acclaim. The novel focuses on the love story of two enslaved men during the 19th century and their struggle to retain this small facet of themselves as another enslaved man begins preaching to garner favor with their enslaver.

His work, while fiction, contains lines of text that read like poetry and demand to be reread over and over as one processes both the cruelty and beauty of his prose.

The novel won the 2022 Publishing Triangle Edmund White Award for Debut Fiction and was a finalist for the 2021 National Book Award for Fiction. The Prophets has been translated into at least 12 different languages.

Jones has published in the celebrated anthologies Four Hundred Souls and The 1619 Project. He is currently working on his next book.

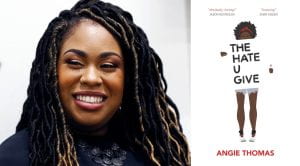

Angie Thomas

For those who are fans of young adult literature, Angie Thomas has become an established name in the genre. Her work has hit the big screen, and though The Hate U Give does not explicitly mention organizations like Black Lives Matter, due to the timing of the movie’s release, it does feature BLM-esque organizations. It is important though that this work not be conflated with the actual people of BLM.

Thomas was born and raised in Jacksonville, Mississippi, and attended Belhaven University where she received her BFA in creative writing. In fact, her New York Times bestselling novel, The Hate U Give, began as her senior project in college.

She has since published five works with two being made into major motion films. If you enjoy young adult literature, check out some of Angie Thomas’ works here.

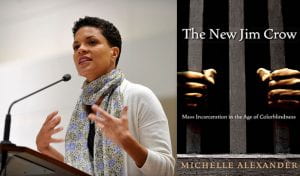

Michelle Alexander

Michelle Alexander is more than just a renowned author, she is also a civil rights lawyer, advocate, and legal scholar.

Her book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, helped transform the national dialogue surrounding the imprisonment of Black Americans. It was published in 2010 and has spent over 250 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list.

Her haunting and true words from her book pierced through veils of dismissal on the ever-worsening problem of racial policing in the United States:

“We have not ended racial caste in America; we have merely redesigned it.”

She has worked both in academia and the public and private sectors, engaging in civil rights litigation and even serving as the Director for the Racial Justice Project in Northern California.

Her work and her writing have had profound impacts on our legal systems and continue to urge for reform. Check out her work alongside that of Isabel Wilkerson to learn about racial caste systems in the United States.

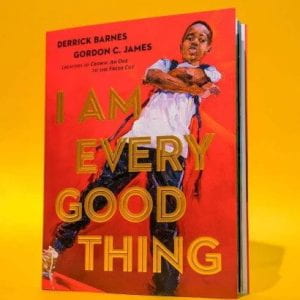

Derrick Barnes

Derrick Barnes is an award-winning children and young adult author. Several of his books have become critically acclaimed.

His book Stand!-Raising My Fist For Justice won the 2023 YALSA Excellence in Young Adult Nonfiction Award and a Coretta Scott King Award Author Honor. His other work, Crown: An Ode to the Fresh Cut, received a Newbery Honor, a Coretta Scott King Author Honor, the Ezra Jack Keats New Writer Award, and the Kirkus Prize for Young Readers. In 2022, he became a National Book Award finalist for his graphic novel Victory.

After he published I Am Every Good Thing, he was nominated once again for a Kirkus Review, making him the first author to ever win the prize for his 12th release.

Before becoming a successful author, Barnes was the first Black creative copywriter hired by the greeting cards giant, Hallmark.

If you’re looking for more novels to diversify your library or classroom, check out Derrick Barnes’ work here.

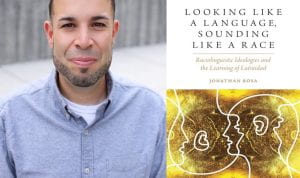

Jonathan Rosa

I want to mention Jonathan Rosa’s work, Looking like a Language, Sounding like a Race: Raciolinguistic Ideologies and the Learning of Latinidad, because of its profound impact on our understanding of how language influences our perception of other racial groups.

Dr. Rosa is a Professor of Anthropology and Linguistics at Standford University whose work focuses on how colonial structures have influenced the construction of racial minorities, resulting not only in institutional inequities but also in linguistic stigmatization.

It is an undeniable fact that we judge a person’s intellect and ability on their written and spoken skills. However, this is never an accurate portrayal of a person’s capability. Jonathan Rosa thoroughly researches this by conducting over 24 months of ethnographic work in a highly segregated Chicago high school. Dr. Rosa unveils how the experiences of young Latinxes are inextricably complicated by racial identity and an imposed view of “proper” speech.

If you are someone who is interested in languages and how we come to understand the world and people through our abilities of speech, you should read this work and challenge ingrained assumptions of racialized speech you may not have even realized you had.

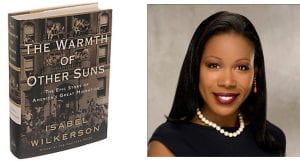

Isabel Wilkerson

Isabel Wilkerson is an acclaimed author of non-fiction that weds poetic narrative with the harsh realities of marginalized communities. Her first work, The Warmth of Other Suns, focuses on the real stories of three people during the Great Migration.

In order to complete her investigative work, she interviewed over 1,200 people and dedicated 15 years to detail the journey of the 6 million people who emigrated from the Jim Crow-oppressed South.

She is the first African American woman to win a Pulitzer Prize in Journalism for her piece on a fourth-grader from Chicago’s southside and two stories reporting on floods in 1993.

She continues to work in journalism for the New York Times and has taught at several prestigious institutions. Her most recent work, Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents, once more displays her incredible talent for incisive research and profound scrutiny of the systems of oppression that plague the United States, Nazi Germany, India, and many more societies.

If you are someone who enjoys historical narratives, Wilkerson’s works are masterful pieces of extensive research alongside bittersweet anecdotes of people living through systemic discrimination.

Conclusion

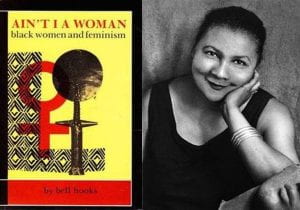

If you liked this book list, check out this list of foundational Black authors here.

To learn more about book bans and their threat to human rights, read the article by Nikhita Mudium: “Book Bans in the United States: History Says it All.”