“Freedom, cut me loose! / Freedom! Freedom! Where are you? / ‘cause I need freedom too! / I break chains all by myself, / won’t let my freedom rot in hell.” – Beyoncé Knowles-Carter, Freedom

Protest is the struggle for recognition of an injustice (see Protests: Movements Towards Civil Rights). The right to rebel against injustice is ingrained within most of the legal frameworks that our society operates under. It is not only expected, but encouraged. The preamble to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) says, “…it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human rights should be protected by rule of law.” Put simply, the UDHR states it is essential to protest when human rights are being denied. Marches, rallies, and demonstrations are common forms of protest, but alternative protest methods can be just as effective as mass public action. One may not consider music, art, film, or science to be mediums for political dissent, but these methods are often surprisingly efficient, especially in the context of a tyrannical government.

Concept Art

Protesters often face government suppression and violence when they attempt to voice any opinions in opposition to the state. Examples throughout history have given us classic acts of protests such as Martin Luther King’s March on Washington and the Arab Spring uprising. However, more subtle acts of protest are necessary within repressive regimes that quickly and easily censor dissidents. Ai Weiwei, China’s most famous political dissident, voices his opinions in an unorthodox manner – art. He famously painted a Coca-Cola logo on a 2000-year-old Han Dynasty urn and later shattered another one in a photo series. The urns were valuable in themselves, being thousands of dollars apiece, but the value lay mostly in the cultural heritage of the objects – the Han dynasty represents the golden era of the Chinese history that many yearn to return to. In response to outrage over the broken urns, Ai says, “General Mao used to tell us that we can only build a new world if we destroy the old one.” We, as American citizens, are used to dramatic public acts of protest, and may find his method to be overly passive and without impact. However, Ai Weiwei has been targeted, beaten, and arrested multiple times in the name of “inciting subversion of state power” (Richburg).

Cultural context is key when understanding the most effective method and medium of protest. An American artist gave a more recent and flagrant example when the artist Christo abandoned a $15 million dollar effort to create an enormous public art display in Colorado. The project, titled Over the River, was an effort to “suspend 1,000 silvery fabric panels” over several miles of the Arkansas River. Over the River was to intrigue and generate dialogue about art; the project had jumped through hurdle after legal hurdle with environmentalist groups and was in its final stages of approval. Planned over a twenty-year period and personally funded by the artist, the effort ceased after the election because the work was set on government-owned land. Christo said, “I use my own money and my own work and my own plans because I like to be free. And here now, the federal government is our landlord. They own the land. I can’t do a project that benefits this landlord” (Capps).

Some of the most deeply moving work to dissent against oppression is done by low-income, underprivileged minority groups. Art is defined within a social context, which is why some forms of art have been glorified as ‘true art’ while others have been demoted. Classical art painted by wealthy artists like Michelangelo are worth millions of dollars and featured in prestigious galleries while art forms that have historically belonged to women like sewing, crafting, and embroidery are demeaned. Up until the Harlem Renaissance, the art world treated black art similarly. Romare Bearden once said, “A concrete example of the accepted attitude towards the Negro artist recently occurred in California where an exhibition coupled the work of Negro artists with that of the blind.” Though Bearden published this essay in 1934, the attitudes towards black art are still not up to par. Society tends to think that the art that makes it into MoMA or the Louvre is end-all-be-all of artistic culture, but work done by professionally trained artists is not any more relevant or significant than work by self-trained artists whose canvas is the streets – the only difference is notoriety. Young black street artists often cannot gain that notoriety because the legacy of oppression has pushed black populations into urban areas and deprived them of resources, rights, and economic mobility. Street art is one way groups choose to protest the political occurrences that have suppressed their ability to thrive.

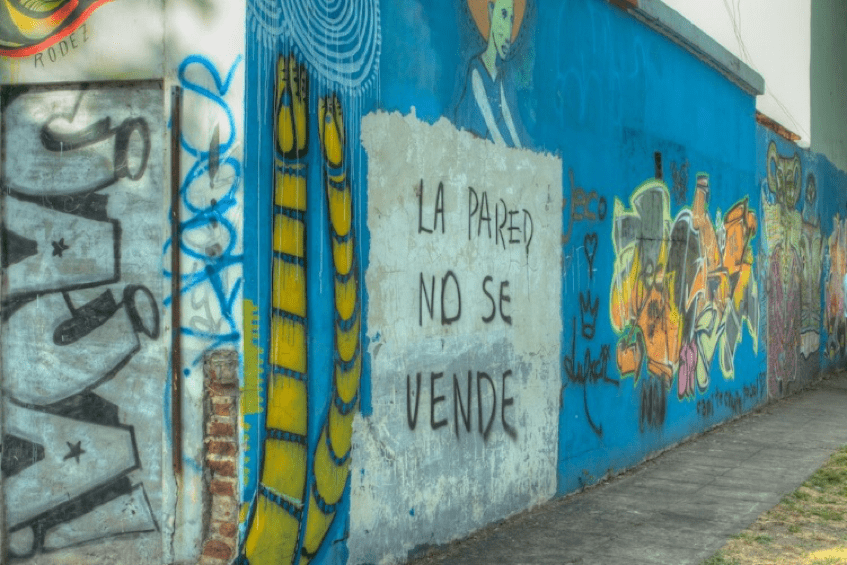

Graffiti as an artistic medium provides young urban dwellers the means to protest their situation through action against the state. One may ask, is graffiti art or vandalism? The short answer is yes. It is art; it is vandalism. Art is relative. The end goal of most art is to evoke a sentiment that influences others emotionally or philosophically. If we look at it this way, graffiti is a more powerful artistic statement than traditional artworks such as Monet’s Water Lilies. The perpetuation of vandalism occurs when artists view their world as divided into cheap real estate for gentrification. Other forces such as war, offensive political rhetoric, and police violence increase the drive to create graffiti. Graffiti artists express their cultural frustration in ways that their peers deem appropriate; often, young black men are denied the ability to express their sadness and fear without being subject to disdain (Aubrey). In a chaotic world often terrorized by police brutality, lack of economic or social mobility, and systematic discrimination, graffiti offers a creative outlet for frustration and allows artists with limited resources to make their voices heard.

Poetry and Music

Poetry and spoken word have also become powerful tools used by many communities with shared cultural trauma. Black women, often dehumanized, commodified and oversexualized by society, have found a powerful outlet in poetry. Poetry gives a path for different communities to express their anger and have it heard in a significant and impactful way. Artistic traditions of expressing hope, fear, and protest are deeply rooted in oppressed communities. This most notably has occurred within the black community, where poetry, song and dance have been tools of cultural unity and generate hope against oppression.

Modern music has adapted to the climate of political tension and has slowly begun incorporating anthems of justice and power. Rap and hip-hop have been particularly strong conductors of this trend. “Rap has developed as a form of resistance to the subjugation of working-class African-Americans in urban centers… rap has the powerful potential to address social, economic, and political issues and act as a unifying voice for its audience” (Blanchard). Beyoncé’s Lemonade centered on themes of justice for the black community after deaths from police brutality. The visuals accompanying Freedom, a track from Lemonade, show the mothers of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and Eric Garner holding photos of their late sons. Hip-hop as a genre has long been a medium for shared feeling within the black community, but artists of all genres have recently been taking stronger and more public stances on political matters.

Celebrities have even taken part in public protests such as when Madonna opened for the Women’s March on Washington in the beginning of the year. Lady Gaga protested after the election by standing outside Trump Tower with “love trumps hate” signs. Green Day protested at the 2016 American Music awards by prefacing their performance with a chant of, “No Trump! No KKK! No fascist USA!” Public figures have adapted to the divisive nature of the times with the incorporation of political statements in their work.

Science

The scientific world may seem limited to hard data, crunching numbers and running tests, but the recent change in administration has caused a shift in how scientists relate to politics. A man who who once called global warming a hoax perpetrated by the Chinese presently leads the United States. Enraged by the blatant dismissal of the scientific consensus that the world is in fact warming, many employees of scientific government agencies have resigned or otherwise protested. The emergence of social media accounts for “rogue” national departments has been a startling revelation. There are currently over a dozen rogue accounts, including @RogueNASA, @AltNatParkSer, and @ActualEPAFacts. These accounts run by actual employees of these agencies who feel that their ability to report accurate information has been censored – a violation of their human rights. Outrage over Trump’s statements on science has even led to a new world record by Autonomous Space Agency Network who achieved the first protest in space in April. They launched a weather balloon with a message attached: a tweet that reads, “Look at that, you son of a *****.” The tweet references a quote by former astronaut Edgar Mitchell, who once said, “You want to grab a politician by the scruff of the neck and drag him a quarter of a million miles out [to space] and say, ‘Look at that, you son of a *****.”

From this, it is easy to see how protest has evolved into a multilateral effort spanning across different segments of society. Music, art and science have all become fertile grounds for innovations in protest. Protest is not always an organized public action. It is often a cultural compilation of attitudes and actions that has formed in rebellion to a societal injustice. Protesting is not always loud, dramatic or direct; cultural and legal differences make some forms of dissent far too dangerous to commit under certain regimes. We cannot always judge others based on their perceived inaction in the face of injustice – protest is a unified effort, executed in a variety of forms, including methods less obvious than others.

Extending or removing support from artists who create political content can be an effective an act of protest for or against their stance. Engaging in scientific debate and spreading awareness of censored issues can effect meaningful change. Taking a moment to admire the work of a graffiti artist can be an act of rebellion. If protests were limited to marching down the street holding picket signs, the world would be at an impasse for change. We must take pride in the forms of protest that are most accessible and most meaningful for us to rebel against injustice and create a better world.