Societal destabilization is a normal part of any dystopian novel. The government cannot come to a consensus, politicians treat countries as puppets, and somehow, an awkward yet powerful adolescent is thrust into the spotlight to save the world. It is slowly dawning on the world that this outlandish twist of fate is now a reality.

In January 2022, Karnataka, a state on India’s southwestern coastal border, banned hijabs in educational institutions. The epicenter of this issue is at the Government Pre-College University for Girls in the Udipi district of Karnataka, where Muslim students say that when they returned to school this past September, they were threatened to either remove the hijab or be marked absent. The girls were not allowed to attend classes or write their exams in their hijabs. This situation is not only a paramount issue and manifestation of India’s growing nationalist agenda, but also signals a threat to a fundamental right guaranteed in the Indian Constitution: religious freedom.

Politics

The Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP), the ruling political party of India, is infamous for its right-wing actions against minorities. The pride of the party, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, is a devout Hindu and believes that a superior India will only be restored to glory by becoming homogenous, a passion increasingly echoed across India. In recent years, minority alienation in terms of religion, caste, and gender has accelerated. Hindu activist groups in Karnataka believe the hijab ban is essential for social equality and for providing an unbiased classroom for every student to learn. Hindu student activists view the hijab as a symbol of the oppression of Muslim girls and wish to remove them for the sake of religious equality in education. They also compare the hijab to a saffron shawl Hindus often wear in religious ceremonies. It was implied that if hijabs are allowed, then every Hindu should be allowed to wear the saffron shawl to class as well.

History

Despite the social equity of this ban, the defense of upholding it is rather weak. This ban forces Muslim girls to choose between their religion, their bodily autonomy, or their education. Who can learn properly when they don’t feel comfortable in their own body? When the hijab is a part of your identity, not wearing it can be a source of ceaseless discomfort and alienation from your body and your perception of yourself.

17-year-old Aliya Assadi, a karate champion in the city of Udupi, summarized the necessity of the hijab in one statement. Much like other Muslim girls, Assadi derives confidence and is assured by wearing her hijab. Removing it is not an option for her because it is a lifestyle that she pays her respects to. Assadi does not feel oppressed in her hijab but being forced to remove it is embarrassing and humiliating.

The National Congress Party, BJP’s competition, vehemently opposes the hijab ban and stated that it is a violation of religious freedom. The BJP’s response asserted that the hijab is not an essential manifestation or practice of Islam, and therefore, the ban is not a violation of the Constitution. The Quran, the primary religious text in Islam, states that “It is not that if the practice of wearing hijab is not adhered to, those not wearing hijab become the sinners, Islam loses its glory, and it ceases to be a religion.” Based on this one quote, the Karnataka High Court deemed the hijab not essential for religious practice, ruled that the ban was constitutional, and dismissed all petitions made by Muslim girls barred from attending class. However, the hijab has more meaning than a literal interpretation of the Koran. Each of the groups that practice Islam in India and across the world have different cultural values and exhibits diversity in their traditions. Similarly, the hijab has underlying traditional value for each person or group, and in some parts of the world, the hijab is a symbol of resistance.

Religious freedom, however, is just the tip of the iceberg. Banning hijabs imposes on equal access to education and women’s rights because, without comfort and peace of mind in oneself, students cannot learn to their optimal ability. Yet, this problem does not extend to male students. This is the reason for their apparent alienation from the education system, which should be teaching them how to be successful and advocate for their beliefs. The right to education without discrimination on religion or gender is a universal human right—a human right that is being violated.

Future Implications

As religious divides deepen between Muslims and Hindus in India, human rights defenders worry that other states will consider enacting a similar ban on hijabs now that the precedent has been set. This is a potential slippery slope that may alienate the Muslim population with additional restrictions and obligations narrowing their sense of self. Already, far-right Hindu groups have claimed that Gujarat, Prime Minister Modi’s home state, is in the process of creating a hijab ban and Uttar Pradesh is next. The majority of both states’ politicians identify as members of the BJP, as well.

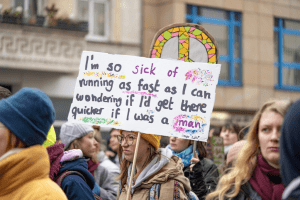

The Muslim girls, however, are not close to surrendering in this fight. They plan to appeal to India’s Supreme Court for a final, unbiased verdict on the case. The young people of India, now the majority age group in the country, are attempting to take India’s future into their own hands. The ramifications of this case, if the Supreme Court were to hear it, will be momentous.

For years, a Hindu nationalist agenda has decreased the rights and autonomy of minorities of all classes. Often, these moves were underhanded and created through loopholes or loose interpretations of the law—just as the hijab ban was. Once the ban’s constitutionality reaches the Supreme Court, the whole country, including the federal administration, will be put on trial for their actions in the past and the future by India’s minority and majority populations.

International Consequences

Unfortunately, islamophobia and minority discrimination are ideologies that have centuries of history behind them, and it will be challenging to fight this growing movement. When we think of history makers and game changers, it is often about one person with enough strength and bravery to face the world. However, lasting progress is sustained by consistent change and accountability. Anyone can fight and advocate against Islamophobia, and, eventually, a little effort from millions can be amassed into a movement capable of changing society from within.

Countless organizations, lawyers, and legislators are facing the brunt of standing their ground against harsher political movements, but the public perspective must change first. In India, is important to communicate the despicable nature of Islamophobia online. Residents can report to the police commissioner or the District Magistrate in-person, or they can tag national authorities on social media such as the Ministry of Home, international human rights groups, and UN agencies. Openly support your neighbors or community members and help them file FIRs against Islamophobia acts and follow directives from local anti-Islamophobic organizations. In America at least, people can support anti-Islamophobic legislation and communicate with their government representatives about their discontent and rage over the treatment of their Muslim counterparts. People can also support American Indivisible and Shoulder to Shoulder, organizations that work to dismantle structural islamophobia. Regardless of your location, demonstrating solidarity and opening honest conversations is an imperative initial step to combating Islamophobia.