On January 21, 2017, over five million people marched–on all seven continents–in solidarity for women’s issues. In Washington D.C, one million marchers made their voices heard, nearly three times the size of the crowd at the inauguration, according to crowd scientists. The Birmingham, Alabama march numbered nearly five thousand, to the surprise of organizers who expected closer to several hundred. The official Women’s March website states the platform and approach is committed to equality, diversity, and inclusion. While initially, the Trump administration may have been the fuel for this rise, the movement presently signifies an international protest against the growing threat of a dishonest narrative about women’s rights and unjust treatment of them.

The sheer numbers of attendees at the march inspired and infused hope into the hearts of many deeply opposed to the injustices within the context of women’s rights. Critics of the march seem to misinterpret the intentions of marchers by claiming that the cause was American-centric, thus ignoring the subjugation of women globally. There is some validity to this, in that, the focus of many marchers remained centered in American political issues, and often excluded some key actors from the discussion like transgender people. However, many critics used these potentially valid grounds to deny the existence of oppression in America. Blogger Stephanie Dolce, after listing a series of wrongs against women in other countries, writes, “So when women get together in America and whine they don’t have equal rights and march in their clean clothes, after eating a hearty breakfast, it’s like a vacation away that they have paid for to get there.” This critical narrative reveals the false impression that many Americans have about women’s rights, the nature of protests, and the human right to participate in protest.

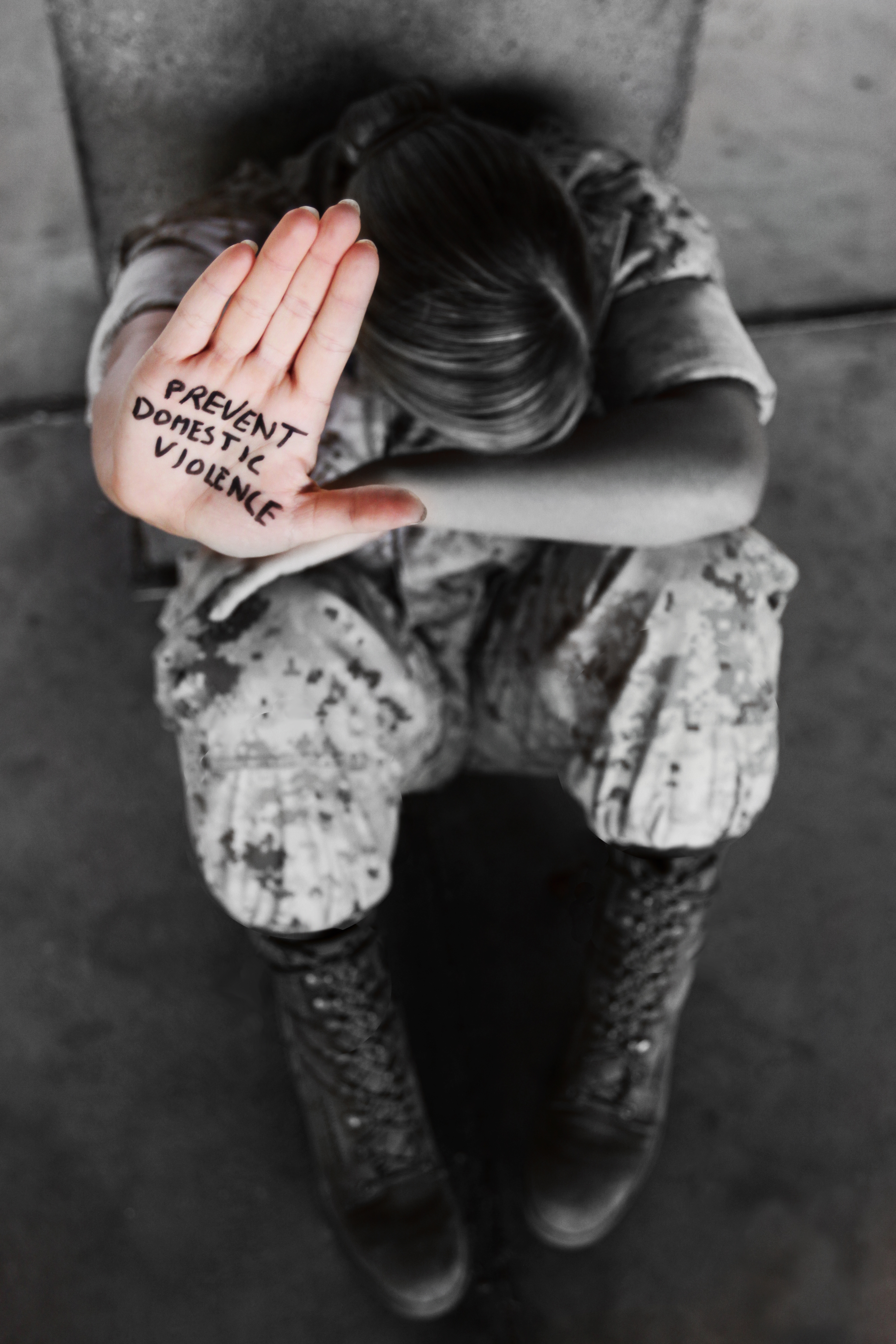

Dolce mentioned the issues of rape, limited education access, gender violence, and denial of bodily autonomy through legislation, infanticide, and female genital mutilation (FGM). She then suggests that American women do not experience these acts of violence and oppression. To believe that these issues are absent in America is to remain blinded by privilege. Dolce’s argument, supported and shared many times across social media, is rooted in privilege—a privilege that often undermines the nature of exploitation and oppression of another because distance rather than proximity and a lack of knowledge discredit the acknowledgement of an experience.

Marchers in cities around the world reflected the microcosm of the global civic society. It is highly unlikely that Dolce, who is vocally critical of the march, attended a protest based on her blog writing. Conversely, I have been an advocate for human rights for years and decided to experience the Birmingham march firsthand. I found myself deeply moved by the variety of issues and identities represented; therefore, I can bear witness to a crowd of people marching for a diverse set of causes, each inherently political but not as a political reaction. Protest signs held high regarding immigration, environmental issues, racism, disability rights, and more, dotted the landscape of Kelly Ingram Park. The diversity of the city was visible in the composition of marchers and their causes. The harsh, judgmental “anti-Trump” rhetoric is an insult to social justice, as this march and subsequent protests, are not about him or any one person.

The highly divisive stage in American politics provides a vehicle of change through shock and outrage; fortunately, the movement is not limited to the American arena. This activism is not a backlash to the election or simply a march about women’s issues. This is not, as some may see it, a petty protest against the shift in ideology represented in our new president. This is the beginning of a global movement to protect rights presently impacted by global structural violence targeted towards women specifically, and humanity generally.

The Women’s March website has listed steps to transform the vigorous energy seen on January 21 into a long-term international movement. Given the millions of marchers who came out, it is hard to imagine that the momentum and awareness for women’s rights will simply fade away. The evolution of the movement is already underway. They currently have two “global action steps” listed and a third still developing. First, communicate concerns for women’s rights by contacting representatives, using postcards or letters with a picture of the march. Second, organize local “next up huddles” which are intended to foster support and community. The goal is that each area brainstorm a “set of actions and strategies our group will pursue in the coming weeks and months”, mobilizing the community through grassroots activism and people power. The grassroots approach, fueled by people power, is essential because it empowers leadership and change from the bottom-up rather than top-down. People power initiates the quicker and more effective change across nations.

With an enormous base of supporters and power of grassroots change, it is clear that the spirit behind the Women’s March is thriving and quickly evolving into a transnational platform.