by Pam Zuber

Menstruation and birth control.

Discussing these topics sometimes makes people uncomfortable. Why? Society sometimes says that we’re not supposed to talk about what happens down there, that they’re just not proper topics for everyday conversation. Could this discomfort be due to the fact that men have often traditionally served as political leaders, media gatekeepers, and educational instructors? Women’s power, voices, and advancement opportunities have been limited. So have their concerns, even if they’re everyday issues that women have faced since the dawn of time.

Such concerns are extremely important to the survival of our species. Menstruation and birth control are crucial parts of life. Without menstruation and everything that accompanies it, we wouldn’t be here. Depending if people have access to it, birth control is also a factor that can greatly improve or hinder a woman’s quality of life. But, these topics are often taboo. People don’t want to talk about them. People often can’t talk about them or do anything about them. Or, if people talk or act on these topics, they may face stigmas and punishments. Living normally during menstruation and controlling one’s reproductive destiny should be vital human rights everywhere. They’re often not, which has created inconveniences, obstacles, and even tragedy. Luckily, individuals and groups are shedding light on menstruation and birth control and how they impact women and the greater culture.

Menstruation discrimination

Although banned by law, menstruation huts are still a reality in some rural areas of Nepal. They’re part of traditions stating that menstruating women or women who have just given birth are impure or the bearers of bad luck. These beliefs have led people to banish menstruating women to live in huts or cattle sheds, prevent them from touching farm animals, and forbid them from eating certain foods.

Known as chhaupadi, this practice of separating women from the general population puts women at risk. Many of the huts lack heat or bathroom facilities or are far removed from the rest of society. In 2019, a woman and her two children died after they inhaled smoke from a fire inside of this type of hut. A teenager died in 2017 from a snakebite she received while staying in a hut. People who live in such huts may have to travel miles to use toilets, wash, and gather supplies. They cannot attend school and their employment opportunities may be limited.

Under chhaupadi, disadvantaged women face even more obstacles that prevent them from overcoming their disadvantages and improving their lives. They do not have the full measure of human rights that males enjoy, simply because they are menstruating. Similar fears about female impurity have long banned women of menstruating age from the Hindu Sabarimala temple complex in India. As part of a number of protests, two women defied this ban and entered the temple in 2019. Their actions sparked further protests for and against women’s rights in the region and ignited international debate.

Positive period news

In a positive period-related development, access to feminine hygiene products is increasing for many. The states of Illinois, California, and New York provide free sanitary products for their public school students. Educational institutions such as the University of Washington also offer such products and other schools are considering it. These efforts are global. The government of Scotland provides free sanitary products to students who attend schools, colleges, and universities as well as to people who visit leisure centers and libraries. Several states in the United States have also removed the sales tax for such products (the tampon tax) or are considering doing so.

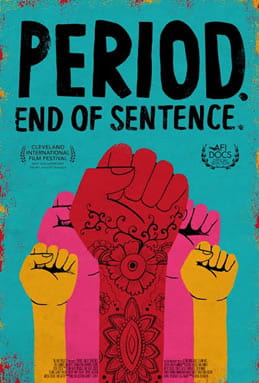

Period. End of Sentence is an Academy Award-winning short documentary that also testifies to the power of proper period care. Directed by Rayka Zehtabchi and produced by Melissa Berton, the film depicts efforts in India to provide sanitary products, end stigma about menstruation, and improve the lives of women and girls. “I can’t believe a film about menstruation just won an Oscar!” said Zehtabchi. The filmmakers acknowledged that Indian initiatives can help girls pursue schooling. “A period should end a sentence, not a girl’s education,” said Berton. Girls in India missed school 20 percent of the time because of menstruation, according to a report by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Females who lack sanitary products might use hay, old fabric, rags, or other products during menstruation, which can lead to unsanitary conditions and infections. It could make menstruation more visible and thus subject to scrutiny and stigma, eroding girls’ self-esteem and confidence in their abilities.

Others question whether menstruation really causes girls to leave school but acknowledge that taboos surrounding menstruation do indeed exist. Supporting girls and women is vital. “Providing girls with a product can only get you so far if you don’t have the enabling environment in the school, supportive teachers, and information about what’s happening to your body,” said Columbia University professor Marni Sommer on a National Public Radio interview. Proper period care “is a human right,” noted Sommer. “We shouldn’t have to justify that girls are deserving of an environment where they can just meet their basic bodily needs.”

Destigmatizing menstruation and providing access to menstruation products may create more equality. If women and girls face discrimination and lack essential hygiene products, they may stay home from work, school, civic engagements, and social events. They cannot fully participate in their lives and the lives of others. People who lack sanitary products live lives similar to women who live under the practice of chhaupadi. Just because they menstruate, women and girls affected by both cannot fully engage with the outside world. People are working to highlight and change this.

The cost of unintended pregnancies

Access to birth control is also an important driver of human rights. Like sanitary products, effective and accessible birth control products provide physical and mental health benefits. Both can be valuable tools for improving and sustaining human rights. Physically, birth control helps women prevent pregnancies. This sounds obvious, but it means so much. Pregnancy and labor take tremendous physical tolls on women. Even after childbirth, breastfeeding mothers’ bodies are not entirely their own, and mothers face the physical and mental strain of raising children and running households.

Mental strain can be considerable for mothers. They are charged with taking care of themselves and their children and completing other tasks, such as working various jobs, helping their families, and fulfilling other responsibilities, not to mention trying to find time to pursue various interests. It can be difficult enough to do those things when they’re deliberate choices when women plan the size of their families. Not having access to birth control makes this precarious juggling act even more difficult. Becoming pregnant unintentionally may impact women’s health since they’re gaining weight, dealing with hormone fluctuations, and experiencing other intense physical changes related to pregnancy. Mentally, they may be facing the stress, anxiety, and depression of unwanted pregnancies and the profound life changes they may create.

Unintentional pregnancies can also burden women and their families financially. Women may take unpaid maternity leaves, turn down promotions or specific positions, or quit their jobs to raise children. They may have to allocate a considerable part of their incomes to pay for childcare. Mothers who re-enter the workplace may not earn the same incomes, have access to the same opportunities, or achieve the same advancements as colleagues who never left the paid workforce. Health and financial issues, unintended pregnancies, and other types of stress can strain women’s relationships with their partners. It could cause women to feel unfulfilled with their lives and feel that they’re not doing all that they want to do because they must fulfill the various responsibilities in their lives.

The worth of birth control

Birth control may shift this balance, helping women do what they want to do instead of what they feel they must do. Access to birth control gives women agency. There are mixed messages about this agency. Just as some higher education institutions are providing sanitary products, some are providing birth control access to their students. Arguably, they’re not providing full access. For example, institutions such as the University of Oregon operate health centers that employ pharmacists who prescribe birth control pills and other forms of contraception. They do so without appointments and charge $15.00 per visit. Not requiring appointments may make it easier for students to visit in spite of busy schedules. Charging $15.00 might make it easier for students for affording such visits. On the other hand, the university isn’t paying for birth control itself. Students must use health insurance or pay out-of-pocket to cover the costs of birth control. This means that people may go without much-needed birth control because they can’t afford it. They may not be able to pay for the $15.00 pharmacist visitation fee or other costs as well.

Sanitary napkins, tampons, birth control pills, and other forms of contraception often aren’t expensive, but the lack of them are. Women who don’t have them may face much more expensive financial, emotional, and physical costs in the future. Providing assistance and access to such items can change an individual woman’s life and transform society as a whole.

About the author: Pamela Zuber is a writer and editor who has written about human rights, health and wellness, business, and gender.