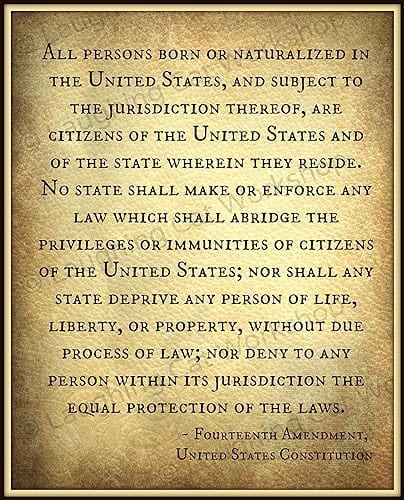

Between the Constitution of the World Health Organization, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, the human right to a high standard of physical and mental health has been determinedly codified in international law. Providing this is more difficult. According to the World Health Organization, mostly low and lower-middle income countries will experience a healthcare shortage of 11 million workers within five years, and an estimated 4.5 billion people already lacked access to affordable essential care in 2021. Evidently, the global healthcare system needs a lifeline; with staff shortages and unmet needs, this help cannot come soon enough. Despite my criticisms of Artificial Intelligence’s implementation in healthcare due to data failures and biases, there is real potential for Artificial Intelligence to make the human right to health more accessible, affordable, and efficient. From wearable devices to Telehealth to risk and data analysis, the implementation of AI within healthcare systems can help relieve medical professionals from menial tasks, provide better access to health services for the disadvantaged, and aid in the overall efficiency of often bottlenecked healthcare systems.

REMOTE SERVICES & WEARABLE PRODUCTS

The access to one’s human right to adequate healthcare can be largely determined by geolocation; rural populations suffer significantly worse health outcomes than their urban counterparts, largely due to isolation from hospitals and medical professionals. People living in rural areas may not have the time or financial means to access efficient, affordable health services. Artificial Intelligence can help address this disparity by powering remote services such as Telehealth, aiding individuals in contacting physicians, and even potentially generating diagnoses without patients’ having to sacrifice their time or resources to travel. The primary use of AI within Telehealth aims to alleviate scheduling problems by training algorithms to match patients with the proper providers and ensure the smoothness of scheduling and accessing virtual appointments. This could significantly reduce the delay in access to Telehealth services that rural patients can experience.

A man measures his heart rate on an Apple Watch

In addition, wearable products utilizing Artificial Intelligence have shown potential in monitoring chronic conditions, eliminating the need for frequent check-ups, and reducing the burden on healthcare providers. Using data collected by wearable devices, AI algorithms can potentially detect signs of health problems and alert those with chronic conditions if their vitals are amiss. Patients can also receive AI-generated reminders to take medications and health check-ins to ensure proper care on a day-to-day basis.

The use of remote Artificial Intelligence technology to provide healthcare services also has the potential to increase access to mental health resources, especially in rural areas, where psychological help may be expensive, far away, or overly stigmatized. AI-driven personal therapists show potential to improve access to mental health services that traditionally are difficult to schedule and afford. Artificial intelligence has been used to analyze sleep and activity data, assess the likelihood of mental illness, and provide services related to mindfulness, symptom management, mood regulation, and sleep aid.

ACCESSIBILITY

On top of increased accessibility for rural residents, various employments of Artificial Intelligence in healthcare have the potential to cater to the needs of those with cognitive or physical disabilities. Models can aid in simplifying text, generating text to speech audio, and providing visual aids to assist patients with disabilities as they receive care and monitor their conditions. The ability of Artificial Intelligence to streamline potentially incomprehensible healthcare interfaces and simplify information can also assist elderly patients in accessing health services. Older people can often be intimidated by the complexity of online healthcare’s technological hurdles, preventing them from effectively accessing their doctors, health records, or other important resources; Artificial Intelligence can be harnessed to adapt user personalization on websites and interfaces to best accommodate the problems an elderly or disabled person may experience trying to access online care.

Generative language models, a particular type of Artificial Intelligence that uses training data to generate content based on pattern recognition, has also been employed to overcome language barriers within medical education. The ability of Artificial Intelligence models to effectively translate educational curriculum has contributed to the standardization of medical practices and standards across countries. The digitalization of this process also makes medical educational material more accessible to those without direct access to a wealth of resources, furthering the World Health Organization’s Digital Health Guidelines, which aims to encourage “digitally enabled healthcare education.” The use of AI as a translation tool within healthcare also shows broader potential to be utilized for patient care, eliminating the need for costly translators and ensuring that non-native speakers fully comprehend their diagnoses and treatments. One example of this is the American company “No Barrier AI”, which employs an AI-driven interpreter to provide immediate, accurate, and cost-effective translation for those with little proficiency in English seeking healthcare.

Elderly man accesses health portal from his laptop

PATIENT AND DATA ANALYSIS

A whole other blog post could be dedicated entirely to the use of Artificial Intelligence in hospitals and as an aid to medical professionals. Broadly, the integration of Artificial Intelligence into clerical and administrative tasks, health data analysis, and care recommendations has reduced the time and money spent on the slow, bureaucratic processes that weigh down medical professionals. Nearly 25% of healthcare spending in the United States is devoted to administrative tasks, but according to a McKinsey & Company study, the adoption of AI and machine learning could save the American healthcare industry $360 billion, mostly by assisting with clerical and administrative tasks. For instance, AI systems have proved effective in boosting appointment scheduling efficiency, speeding up an infamously difficult process. Because of its ability to detect, analyze, and predict patterns, Artificial Intelligence has also been utilized to track inventory and increase supply chain efficiency, ensuring proper amounts of essential medical supplies and medicines are in stock when they are most needed.

Beyond managerial and administrative duties, Artificial Intelligence has also been integrated into clinical decision-making, data and visual analysis, risk evaluation, and even the development of medicines. Trained models have proven capable of analyzing data from brain scans, X-rays, other tests, and patient records to detect and predict health problems; this ability to detect patterns and predict outcomes has also enabled early detection of diseases and conditions such as sepsis and heart failure. Medical professionals can take the model’s analysis into account while also considering treatment suggestions from Artificial Intelligence as they proceed with patient care. This can reduce the likelihood of clinical mistakes as doctors can compare their findings with those of the AI model. Artificial Intelligence has also been used in telesurgical techniques to improve accuracy and supervise surgeons as they operate. The integration of Artificial Intelligence has also advanced vaccine development, as it aids in identifying antigen targets, helps predict a particular patient’s immune response to specific vaccinations, creates vaccines tailored to an individual’s genetic makeup and medical needs, and increases the efficiency of vaccine storage and distribution.

These are only a few examples of the potential usefulness of Artificial Intelligence within healthcare settings. The examples are countless and increasing every day, and, as I believe, the potential for further advancement is immeasurable.

Two doctors analyze a brain scan with suggestions from AI tech

WHAT WE MUST KEEP IN MIND

While these advancements in the accessibility, affordability, and efficiency of healthcare systems show undeniable promise in accessing the human right to health, the development and integration of these Artificial Intelligence technologies must be undertaken with equality at the center of all efforts. As I highlighted in my last post, it is imperative that underlying societal biases be accounted for and curbed within these models to prevent inaccurate results and further harm to individuals from marginalized groups. A survey at the University of Minnesota found that only 44% of hospitals in the United States conducted evaluations on system bias in the Artificial Intelligence models they employed. It is essential to pursue efforts to ensure that Artificial Intelligence promotes not only the human right to health, but also the human right to freedom from discrimination within healthcare practices, especially those aided by systems potentially riddled with bias based on age, race, ethnicity, nationality, and gender.

These technologies are as practical as they are exciting. Still, as the healthcare industry moves forward, Artificial Intelligence developers and healthcare providers alike must maintain the core ideals of the Human Rights framework– equality, freedom, and justice.