WBHM, the publicly sponsored NPR affiliate located in Birmingham, Alabama, published a podcast this year, focusing on the atrocious realities of prisons in Alabama. Titled, “Deliberate Indifference,” the host, Mary Scott Hodgin, takes the listeners through an in-depth journey of the correctional facilities in Alabama, trying to better understand the root causes of the realities the people behind bars face on a daily basis. A health and science writer for the WBHM since 2018, Mary Scott Hodgin has been researching this crisis that Alabama prisons have been facing since 2019. The resulting masterpiece is her podcast, “Deliberate Indifference.”

This blog will highlight some of the themes the limited series focused on, and because this topic is very nuanced, I would not be able to do justice to this discussion in one blog. Hence, this will be a two-part series, where the first part focuses on the background of the prison system as a whole, and the historical context of Alabama’s prison system. The second part will focus on the human rights violations happening in Alabama’s prisons today, including the human rights violations existing in Alabama’s prisons today and the past, and how one can ensure that prisoners are treated with dignity and respect.

I strongly recommend that you please check out the podcast if you have not already because there are many details that I may not be able to get to in this blog or the next one that is worth knowing about. After all, this story is one close to home, and the first step towards finding a solution is having knowledge of the problem at hand. With that being said, let us dive in.

The Origins of the Prison Systems in the Southern States of America

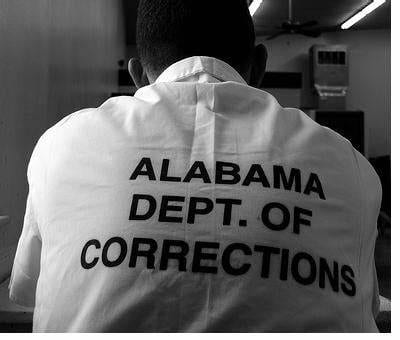

Alabama prisons are recently under federal investigation for the increased violence and sexual assaults that have been rampant for years. This is not the first time the state’s penal system has been under investigation by the federal government. In 2017, Alabama prisons were under federal investigation for the inadequate mental health care offered to the inmates. Before focusing on the details of the prison system, some background information is necessary to fully comprehend how the system got to the place they are in right now. In the podcast, after interviewing various experts on the subject, Hodgin speaks at length about the history of prisons in Alabama. In the 1970s, following a class action lawsuit on the conditions of the prisons in Alabama, Frank Johnson, a federal judge ruled a federal takeover of the Alabama prison system until conditions improved.

As reported in “Deliberate Indifference”, Wayne Flint, a retired Auburn history professor insists that the history of Alabama’s prison system goes further back, starting with the Antebellum era. Flint observes that there were two cultures during that era in the South–a frontier culture and a plantation culture. The frontier culture was only available for people considered “white,” and settlements were disputed with violence. The plantation culture, which was mostly meant for African Americans (who were set free after centuries of slavery following the Union’s victory in the Civil War), focused on the question, “How do you control freedmen?” This was made possible by the loophole included in the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, which outlawed slavery with the exception of imprisoned populations. This meant that new laws …

New laws were created, targeting African Americans, making it possible to arrest and imprison them. These new laws, known as the Black Codes, were obnoxious, to put it kindly, and very racially inspired. The Black Codes included broad vagrancy laws, meaning that any person caught unemployed, begging, or unhoused (to name a few) would be put into prison.

Of course, though there were many white people dealing with poverty at the time, the only ones imprisoned for this were African Americans. Additionally, during the Reconstruction Era, following the defeat of the Confederacy, the Southern states were struggling to rebuild their society and economy. They required cheap labor, and people willing to work long, grueling hours. All this was true at a time when Southerners were not ready to integrate with the then newly freed African Americans and did not want them to have any political power to fight the oppressive conditions they dealt with. Before the Civil War, Flint points out that the majority of people imprisoned, (99%), were White; after the war, Alabama’s prison population was made up mostly of African Americans, (90%).

The Private Sector Benefits from the Prison System

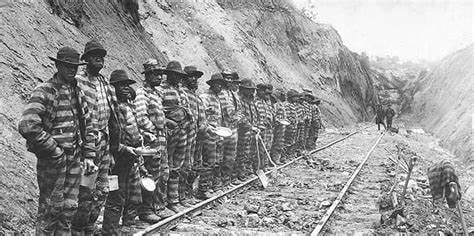

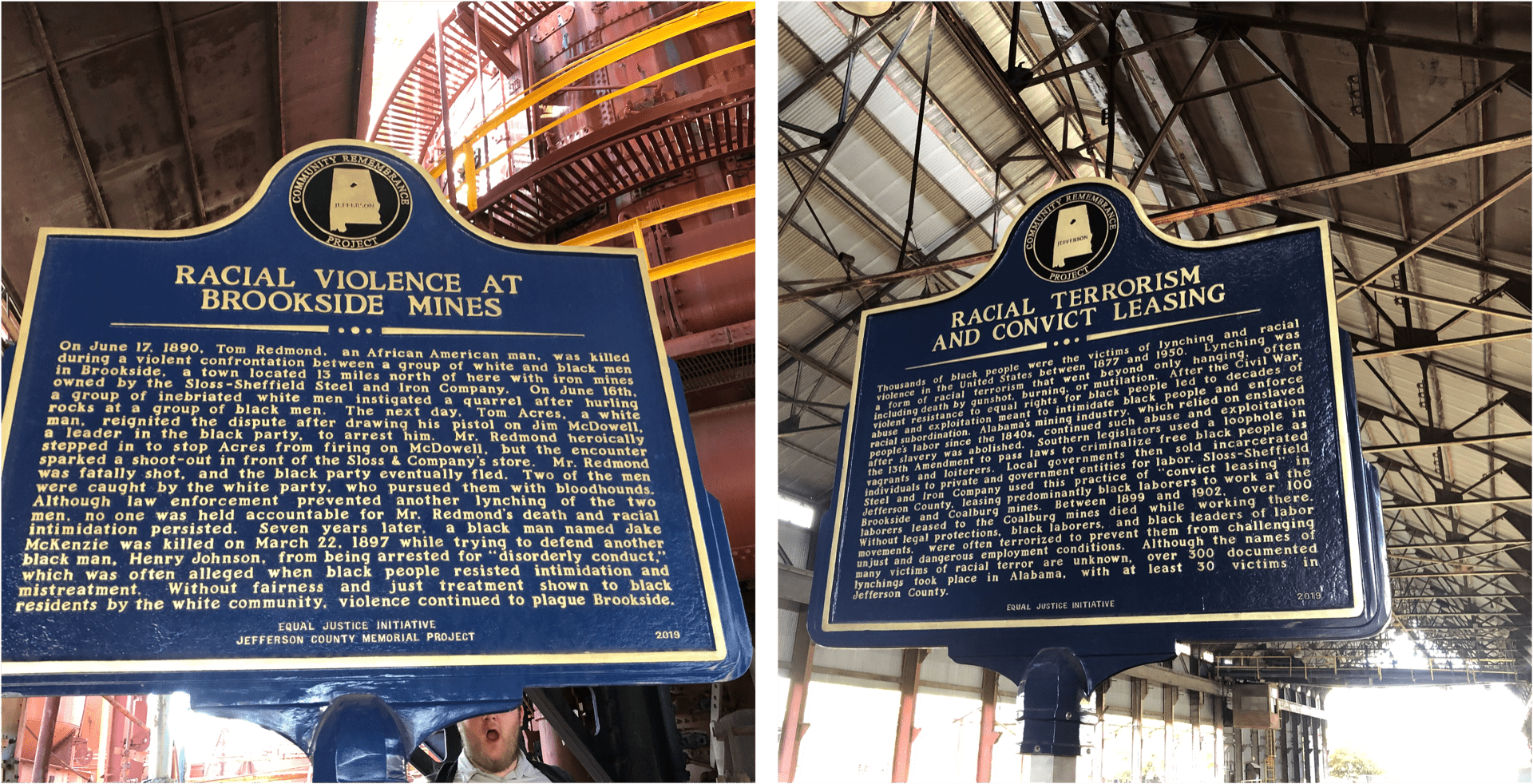

One proposed “solution” to this supposed issue was the convict leasing system. African Americans were arrested for petty crimes, placed in prison, and forced to work with little to no compensation. Due to their incarceration, the inmates’ official records denied them the right to vote. This meant that not only did these states plunge the freed people back into a form of slavery, but they also managed to take away their political power, even after they had served time. Alabama was a state that indulged in this practice. The state did not want to raise taxes, but housing incarcerated people cost the state money. Their solution was to lend prisoners to private companies which paid the state to use the prisoners’ labor; the companies did not pay the prisoners, though, in any form of compensation.

This system became extremely profitable, especially during the Industrial Revolution, which required physical labor. This is how the mining town of Brookside, Alabama grew, and this is the system employed at the famous steel company, Sloss Furnaces in Birmingham. The conditions in which they worked were atrocious during the day, and prisoners were chained to the beds they slept in at night. This system required them to work many days underground with no protection and very little sustenance. Although there were both Black and White prisoners leased under this system, the Black prisoners were treated far worse than their White counterparts. Both Black and White prisoners, if they refused to work, would be beaten, abused, refused access to basic needs, and even could be denied parole. Prisoners were violently abused for any wrongdoings and because much of the public had no knowledge of these activities, the prisoners became an invisible population and were forgotten about.

That was until 1924 when a white prisoner by the name of James Knox was murdered by being dropped into a vat of boiling water for working too slowly. This incident took place in Birmingham, Alabama. Initially, it was reported that Knox’s death was a suicide or an accident. An investigation later revealed not only was James Knox’s death a deliberate act of punishment but also that, following his death, Knox was injected with poison to artificially indicate a suicidal or accidental death.

While this incident is certainly not the only incident that has ever occurred, nor is it the most heinous, this incident, along with other similar incidents where the victim was white, brought attention to the issue of prisoner abuse, and helped put an end to much of the convict leasing, at least leasing to private companies. Unfortunately, the use of convict leasing continued to take place in Alabama and other places even after this case was ruled, but inmates were to be used only for government projects like working on highways and working on farms and cattle ranches. One piece of good news is that in 2022, Alabama voters, along with four other states, voted to close the loophole in the 13th amendment, calling for the state to stop forcing prisoners to work for free. Many other states have shown interest in following this momentum.

The First Time Alabama’s Prisons Experienced a Federal Takeover

In the 1970s, lawsuits were filed against the state of Alabama, the State Department of Corrections, and the governor at the time, George Wallace. Upon further examination of the prisons’ conditions in Alabama, the courts ruled that Alabama prisons were functioning under inhumane conditions and authorized the federal government to step in to address the issues they found in the prisons. There was extreme violence and human rights abuses, and Judge Johnson declared that if Alabama prisons did not comply with his rulings, he would have several of the prisons closed.

Judge Johnson argued that “A state is not at liberty to afford its citizens only those constitutional rights which fit comfortably within its budget.” Judge Johnson provided details on what was expected to change, including improvements in educational opportunities, employment opportunities (with pay), better medical care, sufficient meals, and more space for each imprisoned individual. Governor Wallace, however, denied that there was any problem with Alabama’s prison systems, argued that the involvement of the federal government was an overreach that jeopardized states’ rights, and insisted that this approach by the federal government was disrespectful to the victims of crimes. Unfortunately, Judge Johnson did not see the case to the end; he accepted a higher position, passing on his work to his successor, and in 1988, the federal government ended its oversight of the Alabama prisons.

An unsettling reality becomes clear when comparing the most recent findings and the findings outlined by Judge Johnson – both reports are unnervingly similar, meaning that not much has changed since then. In fact, the issues outlined by Judge Johnson in the 1970s have only exacerbated as the prison population continues to grow, both in Alabama and in America as a whole.

The Racialized Prison System and Its Impacts

The main issue that Hodgin consistently points out in reference to Alabama’s prisons is the overcrowding of prisoners. This issue leads to an entire range of other issues within the prison system, which will be discussed at length in the next blog. For now, the focus is primarily on how this overcrowding issue emerged in the first place.

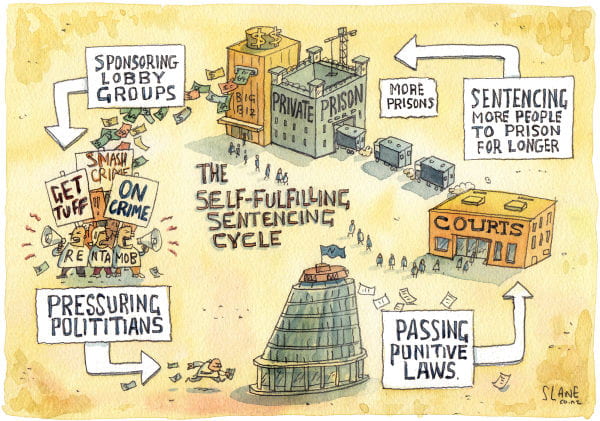

Richard Nixon introduced his idea to wage a “War on Drugs” during the 1970s, with the intention of imprisonment for addicts rather than medical attention and/or treatment. His war had intended targets from the beginning. In an interview conducted years later, Nixon’s own aide stated that their real targets were the leftists who were against the Vietnam War and African Americans in general, but blatantly targeting them would have been constitutionally impossible. Therefore, the War on Drugs was a way for Nixon’s administration to associate marijuana with the leftist “hippies” and heroine with African Americans to disrupt their communities and arrest their leaders. Even though both the white population and black and brown populations used similar amounts of drugs, black and brown communities were disproportionately targeted and imprisoned. Hence, the unequal War on Drugs was implemented, driving up the number of people incarcerated for nonviolent crimes like possessing marijuana and heroin. This contributed massively to the increase in prison populations nationwide, including in Alabama, and this practice has continued to exist to this day, over fifty years since its implementation.

Additionally, while waging his War on Drugs, Nixon also insisted that we must be “Tough on Crimes” in order to justify his war. This approach called for longer sentencing, (even for nonviolent crimes), harsher punishments, mandatory minimums set for certain crimes, and three-strikes rules, all in an attempt to lower crime rates in the nation. The mandatory minimums set mandatory sentencing years for certain crimes, such as drug possession, giving the judges less flexibility to sentence on a case-by-case basis. The three-strikes law, or the habitual felony offender act, (the one in Alabama was passed in 1977 but other states have similar laws in place), sentenced a person to life in prison without parole after their third offense, whether their offenses are violent or nonviolent. The War on Drugs, the tough-on-crime initiative, and the various sentencing laws that followed this era exacerbated the overcrowding of prison populations, including in Alabama.

Nixon’s successor, Ronald Reagan continued Nixon’s War on Drugs, and his wife, Nancy Reagan, started the DARE campaign to teach students across the nation to “Say No to Drugs.” In an attempt to fearmonger the public to support the war on drugs and the tougher sentencing laws, the media played a big role in framing the issue of crime to be a result of increased drug use, a misleading fact that has yet to be proven. In fact, many studies today show that wherever there are high levels of poverty, there will also be an increase in crime rates.

With all this being said, there has been a growing movement in Alabama from both the Republicans and Democrats, to repeal the Habitual Felony Offender Act, citing the overcrowding issues and sentencing that doesn’t fit the crime. The House Judiciary Committee of Alabama approved this repeal in 2021, and the legislation was set to be voted on by the full House. After much research and various combinations of google searches, I found out that the repeal was halted on April 7th of 2022, labeled “dead/failed/vetoed” on the bill tracker website. While this is not the best news, by spreading more awareness of the impact this single piece of legislation has had on many lives in the state, there is hope that with increased support, it may pass in the future. However, this alone will not be enough to address the issues facing Alabama prisons.

In the upcoming blog, we will focus on the prison conditions, details of the 2017 reports and 2020 reports, how the pandemic has exacerbated these issues, and some ways to move forward. In the meantime, listen to “Deliberate Indifference” by Mary Scott Hodgin, and stay tuned for the next part of this series.

Published by