Consider the time it takes to count to sixty. In those sixty seconds, twenty-four people have just been forcibly displaced from their homes due to conflict and persecution. What are their lives like? Take a moment to imagine what your life might be like as one of the roughly twenty-two million refugees in the world today. Crisis and conflict have created violent or otherwise unsafe conditions in your area of residency. Your home is no longer safe, so you are forced to venture into a strange hostile land with no resources, no safety net, and no choice in the matter. You and your family are victims of circumstance, and yet you experience an onslaught of hostility and discrimination. Your host country denies you of your basic human rights by denying adequate healthcare, reducing access to work, and refusing to let you worship or travel freely. All you want is to go home, but home may not even exist anymore.

Once you have pictured yourself as a refugee, enduring terrible circumstances for the well-being of yourself and your family, then imagine the additional barriers of being a refugee woman with a disability. These compounding factors make your life is then filled even more with fear and uncertainty. As a woman, you are already at a disadvantage; women globally face extraordinary obstacles to their success and wellbeing. You now face further discrimination in the workplace, in education, and in society because of your gender. Now add the complex challenges of being a person with a disability. You are now a member of “one of the most socially excluded groups in any displaced or conflict-affected community.” Your risk for being sexually assaulted or abused now increases substantially. If you have a physical disability, any specialized medical care or transportation is most likely out of the question. Families tend to hide and isolate their family members with disabilities, so you likely will never receive the resources you desperately need. You face insurmountable barriers born of circumstances out of your control: gender, ability, and displacement due to conflict. Though you have done nothing to deserve this fate, this is your reality – just as it is for roughly thirteen million displaced people with disabilities in the world today.

Refugees worldwide face institutional violence in their host countries through mass detention, illegal deportation, and police abuse. Nonviolent discrimination against refugees is just as impactful and much more insidious. There are countless barriers to refugee’s human rights such as the refusal of host countries to allow refugees to practice their religion freely, denial of identity documents that allow refugees to travel or return home, and psychologically damaging hateful rhetoric in many countries. Overcoming these barriers along with the ones that accompany disability and womanhood can seem an impossible task. This is what we call multiple discrimination, where your identity is marginalized on multiple levels. This combination creates a perfect storm that has resulted in the devastation for many women with disabilities. The compounding factors of womanhood and disability create a crisis for refugees who fall in these two categories.

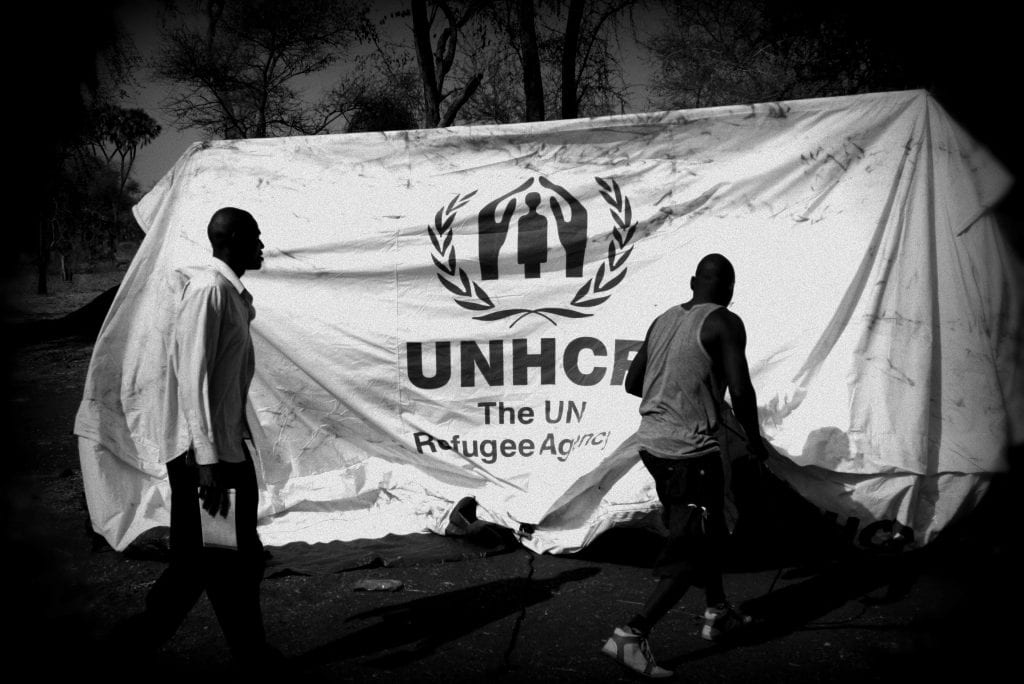

This issue raises questions — what is a refugee, and what does disability look like? The UNHCR defines a refugee as “any person forced to flee from their country by violence or persecution.” Similarly, an IDP (internally displaced person) has been forced to flee their home from violence or persecution, but never crosses into another country. Unlike refugees, international law does not protect IDPs though they suffer from many of the same issues as those with refugee status. The number of forcibly displaced people, which includes both IDPs and refugees, hit a staggering 65.3 million last year according to the UNHCR.

The CRPD defines “persons with disabilities” as individuals who have “long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which, in interaction with various barriers, may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others.” A report on refugee camps in Kenya, Nepal, and Uganda by the Women’s Refugee Commission showed that over half of refugees with disabilities studied fell in the category of physical, visual, or mild mental impairment. Around 20% had hearing impairments, and about 17% had mild intellectual impairments. Women who identified as having a disability were most concerned with inadequate medical care, and secondly concerned with the lack of empowerment and inclusion. Interviewees relayed a lack of physical accessibility in refugee camps, and women from adolescent to senior reported high risks of sexual violence and abuse. This does not take into account the number of invisible disabilities (disabilities that are not obvious or apparent to others) or the number of persons who are isolated from the public by their families, as all the people interviewed self-identified as having a disability.

A 2008 report by the Women’s Refugee Commission found another disturbing trend: persons with disabilities are rarely counted in refugee registration or data collection, and thus never receive specialized resources to aid with disability management. Little attention and even fewer resources are allocated towards the unique concerns of women with disabilities. Bathing facilities, education centers, and distribution sites all commonly had accessibility issues, which makes practicing good personal hygiene, obtaining proper education, and accessing equal resources impossible. This is an obstacle for both men and women with disabilities, but lack of personal hygiene can be detrimental for those who menstruate. Reproductive health for women with disabilities is a major issue—there is a severe shortage of knowledge and inclusion for many refugee women with disabilities. Additionally, the lack of accessible hygiene facilities and lack of adequate healthcare in refugee camps directly violates the standard set by Article 28 of the CRPD that recognizes the “right of persons with disabilities to an adequate standard of living for themselves and their families,” as well as the right for equal healthcare opportunities outlined in Article 25.

Limited physical accessibility in camps results in many refugees with disabilities forced to stay in their homes. This isolation only increases the risk of sexual assault and abuse that is already prevalent in the disabled population, and creates a dangerous situation for women and girls with disabilities who are trapped in their homes and do not have the means to defend themselves or to report their attackers. This situation occurs because displaced people with disabilities are “less able to protect themselves from harm, more dependent on others for survival, less powerful, and less visible” (Women’s Refugee Commission). Further barriers block people with disabilities when attempting to report gender-based violence. Inadequate transportation, lack of accessible communication methods, and discrimination all contribute to the underreporting of gender-based violence against people with disabilities.

It is essential to improve the means of data collection so that people with disabilities are represented when resources are being allocated. This is a crucial step before accessibility in refugee camps can improve. Some attention has been paid to the topic and there is a general trend towards improving humanitarian aid for people with disabilities. The Women’s Refugee Commission is committed to increasing disability inclusion in aid efforts around the world, and publishes reports on their findings. Disability programs based on the topic of gender-based violence have been widely successful, and program participants have responded with overwhelming positivity. “Stories of Change” is one program by the WRC and the International Rescue Committee that shares the stories of women with disabilities and their caregivers. Sifa, a sixteen year old girl with physical disabilities in Kinama Camp, Burundi, shares her experience:

“Over the past year, I have most enjoyed going to awareness sessions. It is important to me that the community sees me as not just a girl without a leg, but as a person with rights and a future. I also really appreciate the materials from IRC, especially sanitary napkins and supplies, because often people forget that girls our age need them. With my new leg and my chance to have an education, I feel safer, smarter and less likely to be taken advantage of.”

Though promising, much work remains in the field of humanitarian aid for women with disabilities. While transparency and accessibility have improved, we should not become satisfied with any standard of living that is less than ideal. Women with disabilities have the right to the same freedoms as more privileged refugees, and refugees have the same rights as every human on Earth. Water, food, hygiene, shelter, freedom from violence, work– all of these items are absolutely and unequivocally vital as a human right as enshrined in the UNDHR. For too long we have settled for inadequacy for people with disabilities because society demonizes and rejects them as human beings. As we have raised the standard of human rights, we must continue to emphasize the most vulnerable people who suffer from compound discrimination. To champion the rights of women must include all women. This unequivocally includes the rights of displaced persons along with the rights of people with disabilities; gender directly impacts both one’s experience with ability and displacement. We can and must strive to do better in our fight for the rights of one of the most marginalized populations around the world.