By Delisha Valacheril

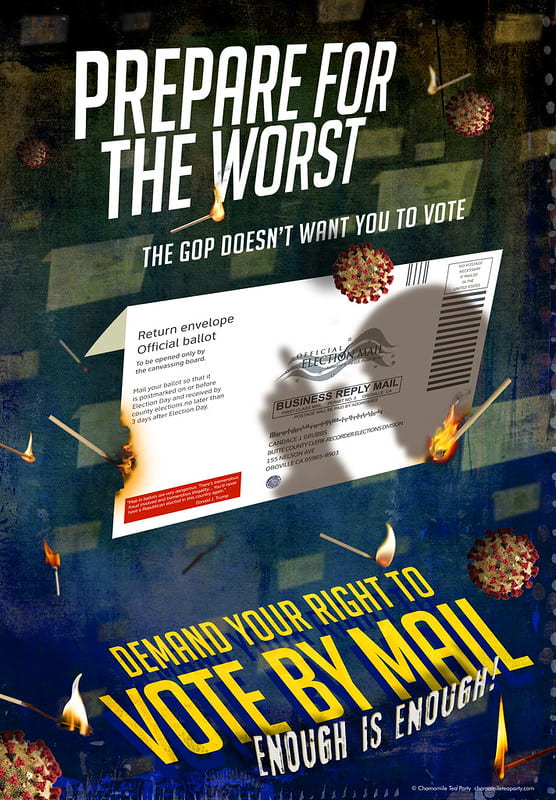

In the United States, the right to vote is heralded as a cornerstone of democracy, in which every citizen can access the ballot box. However, recent legislation in Alabama has cast a shadow over this fundamental right, prompting a fierce legal battle to uphold the principles of democracy and accessibility in the electoral process. Alabama Senate Bill SB1 imposes stringent restrictions on absentee ballot assistance. The new law imposes misdemeanor penalties for returning someone else’s ballot application or distributing an absentee ballot application containing a voter’s personal data, like their name. The payment of someone to distribute, order, collect, deliver, finish, or prefill another person’s absentee ballot application is a felony act that carries a maximum 20-year jail sentence. Aimed at combating “ballot harvesting,” a type of voter fraud that involves submitting completed ballots by third-party individuals rather than by voters themselves, the legislation criminalizes certain forms of aid provided to vulnerable voters, including the blind, disabled, and illiterate, who rely on assistance to exercise their constitutional right to vote. Extensive research, however, shows that voter impersonation is essentially nonexistent, fraud is extremely rare, and many purported cases of fraud are actually errors made by administrators or voters. The Brennan Center’s seminal report, The Truth About Voter Fraud, conclusively demonstrated that most allegations of fraud turn out to be baseless and that most of the few remaining allegations reveal irregularities and other forms of election misconduct.

Historical Context

The restrictions that accompany this new law not only infringe upon fundamental constitutional rights but also perpetuate a legacy of voter suppression that has long plagued Alabama’s electoral system. This has been rooted in the state’s constitution since 1901. When delegates gathered to rewrite the constitution, Chairman John Knox opened the proceedings, saying their goal was “to establish white supremacy in this state.” During Jim Crow segregation, Alabama implemented numerous laws and practices to disenfranchise Black voters. These discriminatory practices included poll taxes, literacy tests, and grandfather clauses, which limited Black people’s right to vote. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed as a result of the first failed march for voting rights from Selma to Montgomery, which was called “Bloody Sunday” and concluded with an attack on protesters. There have been several instances in Alabama’s history that contributed to systemic voter suppression.

Since then, there have been various forms of voter disenfranchisement in terms of redistricting, strict voter ID laws, and lack of accessibility for absentee voting. In Alabama, absentee voting is allowed only with a specific excuse. Voters must expect to be away from their county on Election Day, have a physical disability, or be scheduled to work a shift of 10 or more hours on Election Day to request an absentee ballot. This policy is completely unnecessary and imposes outdated, inconvenient restrictions on eligible voters. The challenges faced by low-income individuals, rural communities, Black Alabamans, the elderly, and those with disabilities have only worsened as a result of Alabama’s inability to enact these reforms. The lack of accessibility in Alabama’s election system was not intended with these marginalized populations in mind.

Implications

SB1 adds to these restrictions because now people who have a valid excuse, such as a disability, are penalized for using absentee ballots. One of the law’s key provisions prohibits individuals from assisting others with absentee ballots, criminalizing acts as benign as providing a stamp or sticker to a neighbor in need. Due to restricted transit alternatives or physical disabilities, voting is already difficult for many residents, such as homebound individuals, retirees, and the elderly. This is designed with a blatant disregard for vulnerable voting groups under the pretense of preventing voter fraud. Allowing this form of blanket prohibition not only undermines the spirit of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which sought to remove barriers to voting for marginalized communities, but also stifles the efforts of grassroots organizations striving to empower voters.

Alabama’s law creates new hurdles to voting, escalates already-existing inequities, and criminalizes assistance that helps marginalized voters participate in the political process. Enacted amidst heightened partisan tension due to the 2024 presidential election, the law has sparked widespread condemnation from civil rights organizations and voting advocacy groups. The Alabama State Conference of the NAACP, the League of Women Voters, Greater Birmingham Ministries, and Alabama Disabilities Advocacy Program are A few years ago, a similar case was presented to the US Supreme Court, Milligan v. Allen, in which a coalition of civil rights organizations sued against the state’s enacted congressional redistricting, stating it was racial gerrymandering, the map-drawing process was intentionally used to benefit a particular race. The Court upheld the district court’s decision and required Alabama to create a second majority Black congressional district in compliance with Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

Final Thoughts

This problem goes beyond party politics and touches on democracy. Regardless of circumstances, everyone deserves unrestricted access to the ballot box in a country built on equality and freedom. The court dispute is a harrowing reminder of the continuous fight to preserve voting rights and protect democratic principles for future generations as it plays out. SB1 perpetuates obstacles that Alabamians with disabilities, the elderly, and home-bound individuals encounter daily. These people oftentimes have to travel further, wait in longer lines, and jump through more bureaucratic hoops than other people. Absentee voting increases accessibility, allowing these voters’ voices to be heard. Restrictive legislation like this is designed to keep eligible voters out of the voting booth. Twenty-eight states already have no excuse for absentee voting in place for November. Criminalizing assistance that provides access to the voting process to others limits participation for Alabama’s most vulnerable citizens.

Voter fraud is wrong, but rather than enacting laws that will make it more difficult for millions of eligible Americans to exercise their right to vote, we should focus on finding answers to real issues. All Alabama citizens need to be able to vote in the November election, and they need to be able to trust the results. This can be achieved by countering the misinformation about mail-in/absentee voting. Instead of passing SB1, voters must appeal to Congress to supply the necessary funds to help states with less experience processing absentee ballots. Voter fraud is a serious issue; however, the right to vote is a Constitutional right enshrined in this country’s foundation. Before preventing any fraud, protecting all citizen’s right to vote should be paramount. Despite all the obstacles in this unprecedented moment, Americans will vote this year, possibly in record numbers. It’s not a matter of whether tens of millions will do so by mail but whether they will have their voices heard.