My first English professor here at UAB centered our composition class entirely around Artificial Intelligence. He provided our groups with articles highlighting the technology’s potential capabilities and limitations, and then he prompted us to discuss how our society should make use of AI as it expands. Though we tended to be hesitant toward AI integration in the arts and service industries, there was a sense of hope and optimism when we discussed its use in healthcare. It makes sense that these students, most of whom were studying to become healthcare professionals or researchers, would look favorably on the idea of AI relieving providers from menial, tedious tasks.

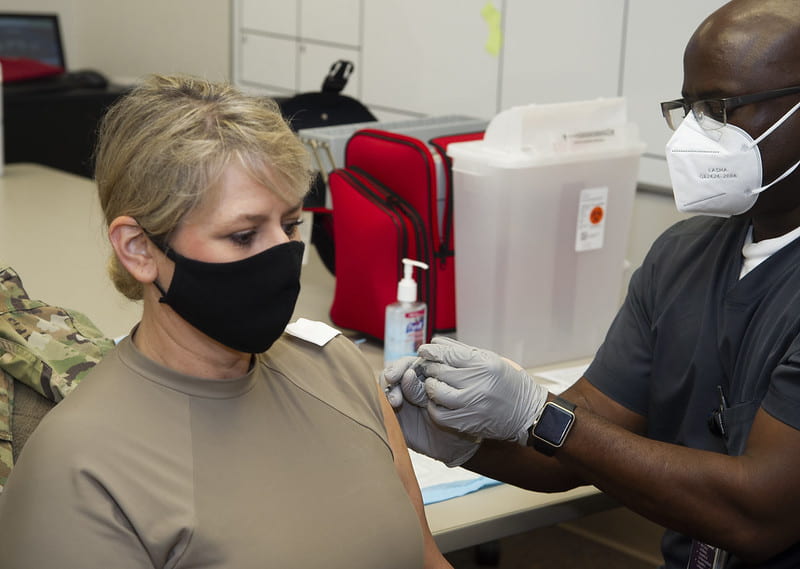

AI’s integration in healthcare does have serious potential to improve services; for example, it’s shown promise in examining stroke patients’ scans, analyzing bone fractures, and detecting diseases early. These successes don’t come without drawbacks, however. As we continue to learn more about the implications of AI use in healthcare, we must take into account potential threats to human rights, including the rights to health and non-discrimination. By addressing the human rights risks of AI integration in healthcare, algorithmic developers and healthcare providers alike can implement changes and create a more rights-oriented system.

THE INCLUSION OF INEQUALITIES

Artificial Intelligence cannot operate without data; it bases its behaviors and outcomes on the data it is trained on. In healthcare, Artificial Intelligence models rely on input from health data that ranges from images of melanoma to indicators of cardiovascular risk. The AI model uses this data to recognize patterns and make predictions, but these predictions are only as accurate as the data they’re based on. Bias in AI systems can often stem from “flawed data sampling,” which is when sample sizes of certain demographics are overrepresented while those of others, usually marginalized groups, are left out. For example, people of low economic status often don’t participate in clinical trials or data collection, leaving an entire demographic underrepresented in the algorithm. The lack of representation in training data also generally applies for women and non-white patients. When training datasets are imbalanced, AI models may fail to accurately analyze test results or evaluate risks. This has been the case for melanoma diagnoses in Black individuals and cardiovascular risk evaluations in women, where the former model was trained largely on images of white people and the latter on the data of men. Similarly, text-to-speech AI systems can omit voice characteristics of certain races, nationalities, or genders from training data, resulting in inaccurate transcriptions.

The exclusion of certain groups from training data points us to the fact that AI models often reflect and reproduce already existing human biases and inequalities. Because medical data reflects currently existing healthcare disparities, AI models train themselves in ways that internalize these societal inequalities, resulting in inaccurate risk evaluations, especially for Black, Hispanic, or poor patients. These misdiagnoses and inaccurate evaluations create a feedback loop where an algorithm trained on poor data creates poor healthcare outcomes for marginalized groups, further contributing to healthcare disparities.

FRAGMENTATION AND HALLUCINATION

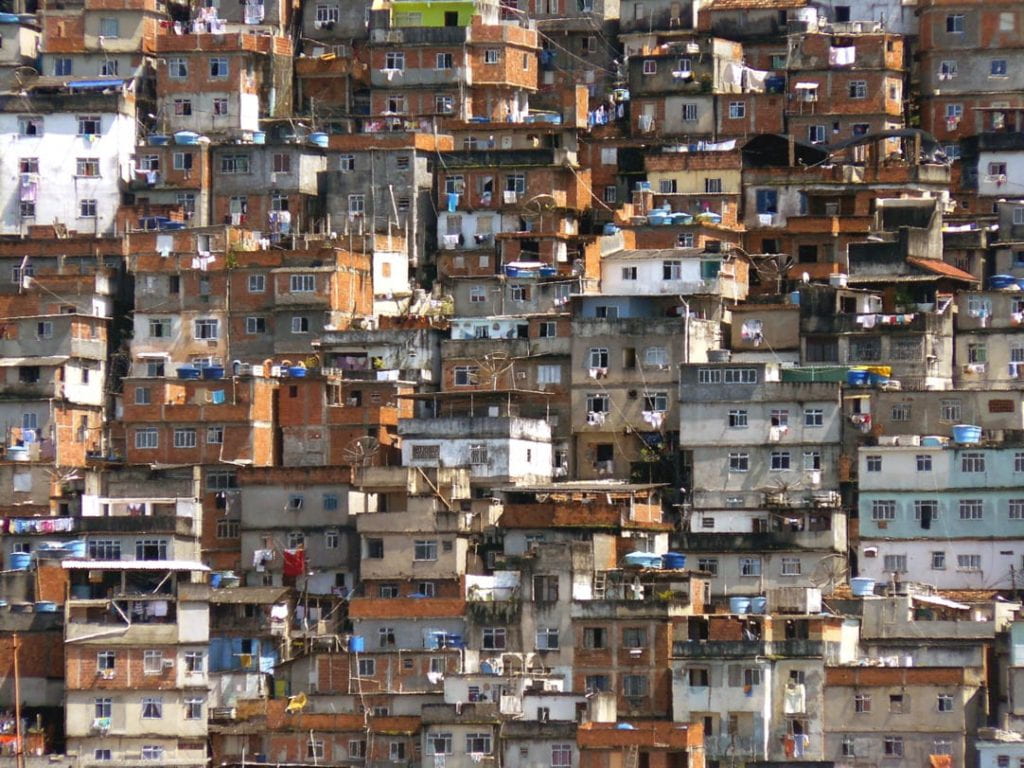

Another limitation of the data healthcare AI models are trained on is their fragmented sourcing. Training data is often collected across different sources and systems, ranging from pharmacies to insurance companies to hospitals to fitness tracker records. The lack of consistent, holistic data compromises the accuracy of a model’s predictions and the efficiency of patient diagnosis and treatment. Other research highlights that the majority of patient data used to train algorithms in America comes from only three states, limiting its consideration of geo-locational factors on patient health. Important determinants of health, such as access to nutritious food and transportation, work conditions, and environmental factors, are therefore excluded from how the model diagnoses or evaluates a patient.

When there are gaps in an AI system’s data pool, most generative AI models will fabricate data to fill these gaps, even if this model-created data is not true or accurate. This phenomenon is called “hallucination,” and it poses a serious threat to the accuracy of AI’s patient assessments. Models may generate irrelevant correlations or fabricate data as they attempt to predict patterns and outcomes, resulting in overfitting. Overfitting occurs when models learn too much on the training data alone, putting weight on outliers and meaningless variations in data. This makes models’ analyses inaccurate, as they fail to truly understand patient data and instead manipulate outcomes to match the patterns they were trained on. AI models will easily fabricate patient data to create the outcomes that make the most sense to their algorithms, jeopardizing accurate diagnoses and assessments. Even more concerning, most AI systems fail to provide transparent lines of reasoning for how they came to their conclusions, eliminating the possibility for doctors, nurses, and other professionals to double-check the models’ outputs.

HUMAN RIGHTS EFFECTS

All of this is to say that real patients are complex, and the data that AI is trained on may not accurately represent the full picture of a person’s health. This results in tangible effects on patient care. An AI’s misstep in its analysis of a patient’s health data can result in prescribing the wrong drugs, prioritizing the wrong patients, and even missing anomalies in scans or x-rays. Importantly, since AI bias tends to target already marginalized groups such as Black Americans, poor people, and women, unchecked inaccuracies in AI use within healthcare can pose a human rights violation to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) provisions of health in Article 25 and non-discriminatory entitlement to rights as laid out in Article 2. As stated by the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, human rights principles must be incorporated to every stage of AI development and implementation. This includes maintaining the right to adequate standard of living and medical care, as highlighted in Article 25, while attempting to address the discrimination that occurs within healthcare. As the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights states, “non-discrimination and equality are fundamental human rights principles,” and they are specifically highlighted in Article 2 of the UDHR. These values must remain at the forefront of AI’s expansion into healthcare, ensuring that current human rights violations are not magnified by a lack of careful regulation.

WHAT CAN BE DONE?

To effectively and justly apply Artificial Intelligence to healthcare, human intervention must ensure that fairness and accuracy remain at the center of these models and their applications. First, the developers of these algorithms must ensure that the data used for training is drawn from a diverse pool of individuals, including women, Black people, and other underrepresented groups. Additionally, these models should be developed with fairness in mind and should work to mitigate biases. Transparency should be built into models, allowing providers to trace the thought processes used to create conclusions on diagnoses or treatment choices. These goals can be supported by advocating for AI development teams and healthcare provider clinics that include members of marginalized groups. The inclusion of diverse life experiences, perspectives, and identities can remedy biases both in the algorithms themselves and the medical research and data they are trained on. We must also ensure that healthcare providers are properly educated about how these models operate and how to interpret their outputs. If developers and medical professionals do address these challenges, then Artificial Intelligence technology has immense potential to improve diagnostic accuracy, increase efficiency in analyzing scans and tests, and alleviate healthcare providers of time-consuming, menial tasks. With a dedication to accuracy and human rights, perhaps the integration of Artificial Intelligence into healthcare will meet my English classmates’ optimistic standards and aid them in their future jobs.