While I do not soon foresee a diamond in my future, I have been able to witness the happiness a diamond ring brings to the lives of other people. A diamond ring represents love and commitment, and nothing can be purer than that. Imagine my surprise when I learned in my economics class that a significant number of diamonds, called blood or conflict diamonds, can be linked to horrific suffering and bloodshed. A good number of these conflict diamonds can be traced back to one company: De Beers.

De Beers diamond company was founded in the 1800s by Cecil Rhodes in South Africa. Before 2000, the goal of De Beers was to effectively and efficiently buy as much of the world’s supply of diamonds as possible so as to be able to determine the price and guarantee price stability. This tactic earned the company the nickname “the custodian” of the diamond industry. In 2000, De Beers controlled around 65 percent of all diamond production, while in 2001 De Beers marketed two-thirds of all the rough diamonds in the world and produced nearly half of the world’s supply of diamonds from their mine. The company employed strategic marketing tactics to maintain their power and growth worldwide, effectively influencing the perception of diamonds to what it is today. For example, the phrase, “A Diamond is Forever,” was coined in a De Beers ad campaign. De Beers influenced the choice of a diamond as the centerpiece for an engagement ring and even the price of the ring to be two months’ salary. The Washington Post described De Beers as “a global cartel controlling mining, distribution, and pricing.”

For a company that produces a product to signify love, such as an engagement ring, De Beers has left a significant amount of bloodshed and controversy in its wake. The company has been banned from operating or selling inside the United States borders since 1996 over a price-fixing case. In the 1990s, De Beers bought billions of dollars’ worth of diamonds from conflict ridden areas in Africa, which in turn provided the means for rebel groups to obtain weapons and supplies on the black market. In the mid to late 1900s, De Beers benefited from the South African apartheid because the system of black repression ensured cheap labor for the mines, protecting the company from being hurt by the diamond boycotts sweeping the world at that time. The company became scorned as more and more information regarding conflict diamonds and De Beers’ blatant disregard for the harm conflict diamonds can cause became public.

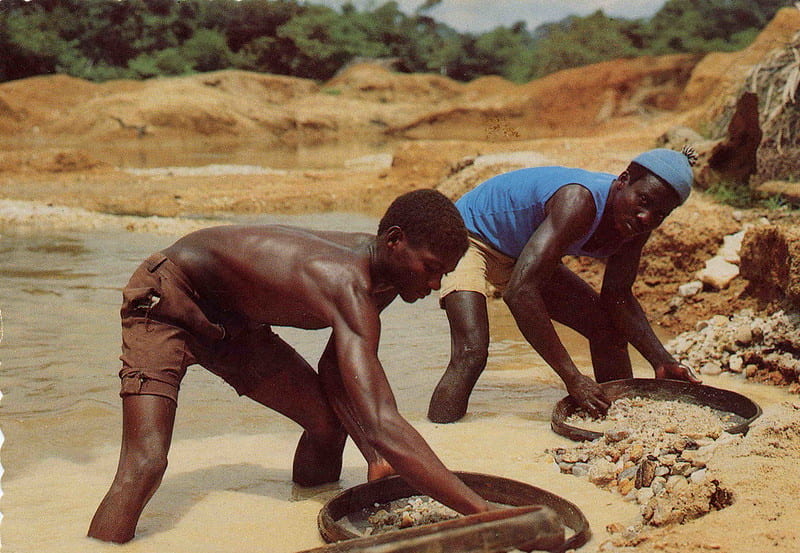

The definition of conflict diamonds, as written by the United Nations, is as follows: “diamonds that originate from areas controlled by forces or factions opposed to legitimate and internationally recognized governments, and are used to fund military action in opposition to those governments, or in contravention of the decisions of the Security Council.” Armed groups use the revenue from exploiting diamond mines and diamond workers to fund their personal agendas. Despite the diamond business being an $81.4 billion a year industry, the towns that house the diamond mines do not reflect the wealth that lies below. Many parents choose to send their children to work in the diamond mines in order to earn a meager salary, determined on a diamond-by-diamond basis, instead of sending the children to school. The difficulty that evolves from attempting to eliminate conflict diamonds is that the diamonds traded by rebel groups are physically indistinguishable from the diamonds traded by legitimate groups. Because of the long process a diamond goes through before it reaches the jeweler, it is very difficult to determine the original source of the diamond.

In 2000, De Beers put out a statement guaranteeing that their diamonds did not originate from conflict zones in Africa and promised that their purchasing of diamonds did not fuel any conflicts in Angola and Congo. The statement was met with mixed reviews, some welcoming the initiative the company was taking, and some believing that De Beers would be unable to control the smuggling system that crisscrosses across the continent of Africa. Since the initial statement in 2000, De Beers’ statements have been very contradictory, stating at one point that it would be easy to find the origin of the diamonds and yet continually releasing statements saying that it is impossible to distinguish the origin of the diamonds that they buy. Since 2000, some independent diamond dealers have not only claimed to sell diamond bunches that they bought from rebel groups to De Beers, but also that De Beers was aware of the origin of the diamonds. Currently on their website, De Beers boasts that 100% of their diamonds are conflict free. However, the company only cites the Kimberley Process, a process they helped to create, in regards to this certification.

De Beers’ promises have rested on determining the origin of the diamonds. It has already been stated but is worth reiterating that determining the origin of diamonds has been much disputed as diamonds are handled in groups, making the process of discovering the origin of a diamond very difficult. In 2003, a process named the Kimberley Process was established by the main actors in the diamond industry, including De Beers. The Kimberley Process is so named for the town where De Beers diamond company was founded, highlighting the influence the company had in the establishment of the process. It is an international certification process with the goal of distinguishing conflict-free diamonds from those diamonds associated with a conflict. The Process was created from a meeting in 2000 in Kimberley, South Africa, where the biggest diamond producers and buyers in the world met to address the growing threat of a consumer boycott. Consumers were becoming more aware of the influence the sale of diamonds had in funding to civil wars in Angola and Sierra Leone and were threatening to forgo buying diamonds all together. In 2003, 52 governments and international advocacy groups ratified the Process, creating a system of certifications issued by the country of origin that must accompany any shipment of diamonds. If a country was unable to prove that their diamonds were separate from any conflict, said country could be cast out of the international diamond trade. The Process did marginally reduce the number of conflict diamonds in the market, but the process is ridden with loopholes. It is unable to stop the international sale of the majority of diamonds mined in conflict ridden zones and diamond mining even outside of a conflict zone is terrible work with many of the miners being school-aged minors.

Many argue that the Kimberley Process is not only laced with loopholes, but it also does not go far enough. For example, the Process does not disqualify diamonds mined in an area with human rights abuses. Also, the definition of conflict used in the creation of the Process is so narrow that it excludes many situations that would generally be considered a conflict. The definition used is, “gemstones sold to fund a rebel movement attempting to overthrow the state.” An instance where the definition stated in the Kimberley Process failed occurred in 2008. The army of the government of Zimbabwe seized a diamond mine within Zimbabwe’s borders and proceeded to kill and rape hundreds of miners. Because the army represented a legitimate government, this instance is not considered to be against the Kimberley Process. The Kimberley Process did implement a ban on the Central African Republic when it was discovered that the mining of diamonds helped to fund a genocide of thousands since 2013. However, the UN estimates that $24 million worth of diamonds have been smuggled out of the country since the ban.

While a true fair-trade system would ban diamonds mined in a conflict ridden area and allow consumers to purchase diamonds that could improve the life of artisan workers, ultimately there is no way of truly knowing whether the diamond you buy is in somehow linked to a conflict. The Human Rights Watch has come up with a list of strategies that may help diamond companies fulfill their obligation of “identifying, preventing, mitigating, and accounting for their own impact on human rights throughout their supply chain.” Such strategies include: 1. Establishing a policy regarding the supply chain that is included in the contracts with suppliers 2. Creating a ‘chain of custody’ by requiring documentation for each step along the supply chain 3. Assessing thoroughly and respond promptly to human rights risks at all stages of the supply chain 4. Employing independent, third-party examiners 5. Becoming public with the names of suppliers 6. Sourcing responsibly and being wary of large-scale mining operations. The diamond industry has a long way to go but with established organizations calling out companies like De Beers, loopholes in certification processes can be closed and ultimately conflict diamonds may be eliminated.