More than a year ago, in 2024, a student-lead protest turned violent, after armed forces began attacking. Recently, the former Prime Minister of Bangladesh, Sheikh Hasina, and her Minister of Home Affairs, Asadduzzaman Khan Kamal, were accused of crimes against humanity. Both were found guilty of these crimes on November 17, 2025 by the International Crime Tribunal of Bangladesh. Those in attendance cheered as the verdict was announced; many had been personally affect by the violent attacks on the protest, either by injury or having lost a loved one. The seats meant for Hasina and Kamal remained empty throughout the entirety of the trial. This did little to stifle the pure excitement that filled the walls, inside and outside, as the words death penalty fell from Justice Md Golam Mortuza Mozumder’s lips. For their crimes against humanity, both of the accused are condemned to the ultimate punishment: death.

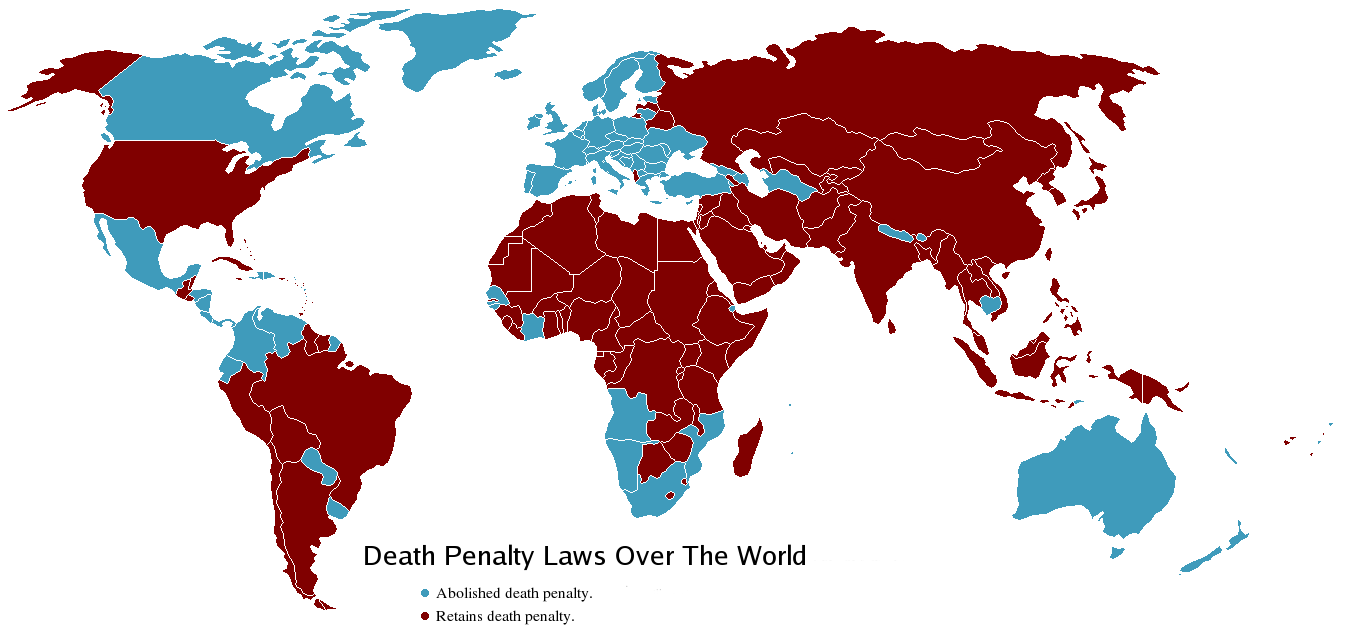

It is worth noting that the death penalty directly undermines the right to life and the right to not experience inhumane punishment. These rights are outlined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). The first, right to life, is discussed in Article 3 of the UDHR and the second, no inhumane punishment, is talked about in Article 5 of the UDHR.

The three week student-led protests in 2024 ended in violence and the death of hundreds of students. The protests were against the reinstatement of a 30% quota that reserved government positions for family members of veterans from Bangladesh’s independence war. In a blog post titled The Awaiting Arrest Warrant of Bangladesh, Tamanna Patel offered an in-depth evaluation of the protests, the escalation of violence, and Hasina’s resignation of power. Building on this, this blog will briefly discuss the events that occurred during the protest, the aftermath of the protest, and Hasina and Kamal’s trial, verdict, and sentencing.

The History and Allegations

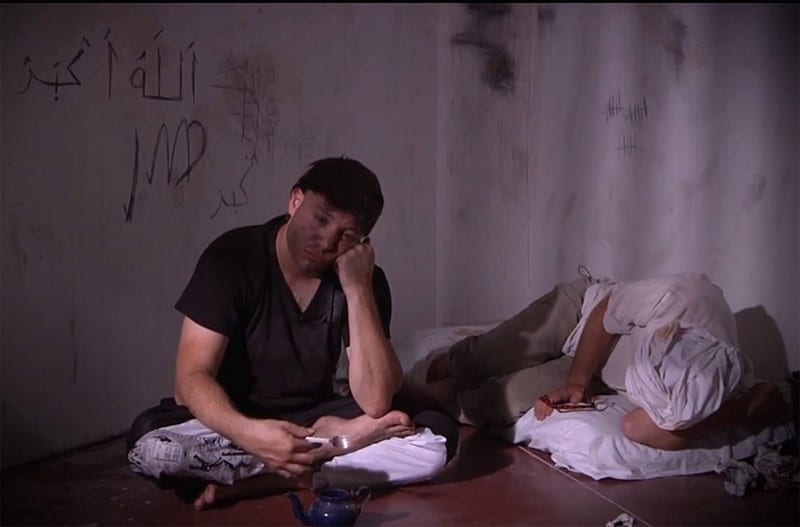

What started as a peaceful protest on July 15th, 2024 by Dhaka University students quickly turned deadly when armed forces began attacking protesters. Batons were swung, guns raised, and tear gas fired into the crowds by members of the Bangladesh Chatra League (BCL) and later by the police. The steadily increasing death toll fueled the discontent amongst protesters. After the country went offline for five days, the death toll rose to 200 and the arrested to a minimum of 2,500.

According to Article 41 of the United Nation (UN) Charter, the Security Council has the right to conduct international tribunals and put those who are accused of heinous crimes, such as crimes against humanity, on trial. In the aftermath of the protests, the International Crimes Tribunal of Bangladesh was tasked with bringing a case forward against Hasina, Kamal, and the former police chief Chowdhury Abdullah Al-Mamun, all of whom played a hand in ordering Bangladesh’s armed forces to use lethal weapon against students during the protests. The attacks on protesters with lethal weapons are considered crimes against humanity. Because of their involvement, all three of the accused were tried for the crime of purposely targeting civilians.

The Trial, Verdict, and Sentencing

The following elements must be met for a crime to be considered a “crime against humanity.” The first is that “the perpetrator killed one or more persons.” In the case of Hasina, Kamal, and Al-Mamun, their orders to use lethal weapons on protesters, which resulted in mass casualties, fulfills the requirement for the first element. The second is that the crimes were “committed as part of a systematic or widespread attack directed against a civilian population.” The student protesters would be the civilian population, and the multiple attacks at various protests across the country within a short time period could be seen as systematic or widespread attacks. The final element is that “conduct was part of or intended … to be part of a widespread or systematic attack against a civilian population.“ For this tribunal, it was essential that the intent behind the attacks on the protesters be proven to be systematic or widespread.

The prosecution’s closing statements on October 16th, 2025 reiterated the severity of the crimes against humanity that Hasina and Kamal committed and called for both to receive the death penalty. The prosecution stated that due to orders by Hasina and Kamal, widespread, systematic attacks were carried out. One of the main arguments supporting this assertion was that members of the Awami League —supporters of Hasina– joined the police in violently attacking student protesters.

The defense, on the other hand, stated that the violence was not widespread, arguing that if it had been, it would have occurred throughout the entirety of Bangladesh. The defense attorney stated that there were not enough witnesses to the violence across the country and that it is possible that some of the videos of violence could be AI. The prosecution team had 54 witnesses and the defense had none. In addition, the defense attorney brought into question the validity of the former chief of police, Chowdhury Abdullah Al-Mamun’s, testimony, as he could just be throwing the blame onto the other two accused.

Experts at the Atlantic Council, a think tank, note that this sentencing might further increase division within Bangladesh. With elections quickly approaching, the former ruling party, Awami League, has essentially been banned from running. Because of this, the possibility of further violence is a valid concern. For some, the death penalty is critical for holding the government accountable. Others believe the sentencing is not justice and will only work to further polarize the people of Bangladesh.

Undoubtedly, this verdict and sentencing have offered the families and friends of those killed in the protest some form of comfort. For many closely affected by the aftermath of the 2024 protests, this is justice. For others, the speed of the trial, absence of the defendants, and the banning of the Awami League from national elections make the tribunals seem politically motivated. While Hasina and Kamal received the death penalty, the former chief of police received only five years in prison. Although he did testify against the two leaders, there is a significant gap in the severity of the punishments. With Hasina and Kamal remaining in India, it is not yet clear whether they will be extradited by the Indian government. Dhaka (where the government of Bangladesh is located) has implemented an extradition treaty, but New Delhi responded that they will do what benefits the people of Bangladesh the most.

Conclusion

Although the fairness of the trial has been brought into question, the consequences of the armed forces attacking student protestors remains. It is evident the people of Bangladesh desire governmental change and accountability for its past actions. Using lethal weapons on civilians is a crime against humanity. For now, Hasina and Kamal have not been extradited, and it is uncertain whether or not their punishment will occur. Indeed, the punishment in itself can be viewed as a human rights violation. While their crimes undoubtedly undermined human life, so too does their sentencing undermine their right to life. It is a vicious cycle of violence that occurs when the death penalty is used. Regardless of their punishment, there is little that can be said to justify such a use of force. Only time will tell whether or not those responsible for such crimes will be punished.