In a region that has so often felt the brunt of capitalist, industrial exploitation, it follows that there ought to be a response on the part of the workers to protect their rights. This has been the case in Appalachia since the industrialists first started setting up shop in the mines and hollers throughout the Appalachian Region. Of particular note are the Coal Wars, which took place in Appalachia from the late nineteenth century to the early twentieth century, from 1890-1921.

Preceding the Coal Wars, workers’ conditions were already very poor. Though the conditions heavily depended on the level of apathy the owners of the coal towns felt or did not feel for their workers (which was usually high), it was nearly universal that coal camps were remote, unhealthy, and unsafe, both due to frequent industrial accidents and poverty-driven crime. Companies often owned the homes of the workers, and eviction was a constant threat. Further, the usage of company stores, in which the only form of currency for the price-gouged goods was company scrip or coal scrip, forced the workers into a monopolistic, unbalanced form of trade where they were always at the mercy of their company. Companies often employed private detectives, public law enforcement, and strikebreakers who used violence, harassment, intimidation, and espionage to crack down on workers’ rights advocates’ activities (Athey).

There was also an ethnicity-based social hierarchy enforced by the companies. Despite all the workers being low-paid, blue collar workers, Welsh and English miners were considered to have the highest prestige and received the best jobs, followed by the Irish. More recent immigrants from Italy and Eastern Europe were treated the worst, with the poorest jobs. However, all groups recognized that it was them against the companies for which they worked. From the mid-nineteenth century forward, coal miners built a strong reputation for radical engagement with politically left ideologies and for militant unionization (Rowland).

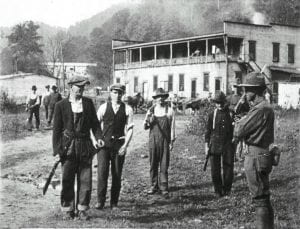

Battle of Blair Mountain, 1921

It was under these pretenses of repression and disregard for workers’ rights that the Coal Wars occurred. While entire books could be written about the Coal Wars, I am going to focus on the Battle of Blair Mountain, which was the largest labor uprising in the history of the United States, as well as the largest armed insurrection since the Civil War, and occurred from late August to early September of 1921. Since 1890, coal mines in Mingo County, West Virginia had hired only non-union workers and specifically denied their miners the right to unionize. When three-thousand miners unionized in spite of this, they were summarily fired. The Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency was brought in to effect the evictions of the miners’ families from the company town. Police Chief Sid Hatfield, along with a group of deputized miners, confronted them and a gunfight ensued, killing the mayor of Matewan and Albert and Lee Felts, among others. Later, Hatfield went to stand trial in McDowell County for an unrelated incident and was assassinated by Baldwin-Felts agents on the courthouse stairs. A friend of Hatfield’s, Ed Chambers, was also killed by a Baldwin-Felts detective who shot him execution-style after he was wounded in the melee. When word got back to the miners that Hatfield had been killed, they began to take up arms and organize, commandeering trains and moving to fortify areas surrounding Blair Mountain.

The Battle of Blair Mountain saw some forty-thousand combatants engage in armed conflict in Logan County, West Virginia. Ten-thousand striking coal miners led by Bill Blizzard faced off with Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency strike breakers, Logan County Sheriff’s deputies led by Don Chafin, West Virginia State Police, and the West Virginia Army National Guard. Approximately one million rounds of ammunition were fired and over one-hundred people were killed, with nearly a thousand miners arrested for murder, conspiracy to commit murder, and treason against the State of West Virginia (Savage).

Decline in Labor Union Membership

It is hard to believe that something like this occurred less than a hundred years ago in our country. Most people, I think, are unaware of the bloody history of labor rights in the United States. Further, it appears that anti-labor sentiment and large industries have prevailed in America. The Battle of Blair Mountain unfortunately led to a decline in membership for the United Mine Workers of America, even if it also led to a greater public knowledge about the conditions in which they worked. In spite of any greater awareness, unions have, since then, continued to hemorrhage members. In 2015, NPR reported that in 1965, almost a third of all workers in the US belonged to a union. By 2015, that number had shrunk to one in ten. Their research indicated that, even at the height of membership, the South/eastern United States saw drastically reduced numbers of union members compared to the Northeast, Midwest, and West. One contributing factor to this may be “right to work” laws, more common in the South, which are state laws that prohibit union security agreements between unions and employers. Right to work laws are misleading in that they are not general guarantees of employment, but are government bans on contractual agreements between employers and union employees requiring workers to join unions if they benefit from their protection.

As I discussed in my last post, unions have been shown to raise wages, reduce wage inequality, and protect rights for workers. Higher rates of union membership tends to indicate greater respect for human rights in industry.

So why are states limiting the function and growth of unions? It seems a shame to me that the interests of large corporations are being given priority to the interests of their workers. This is something we should all be concerned with because workers’ rights are human rights. Workers’ rights encompass things like freedom of association, the right to strike, the prohibition of forced or compulsory labor, and the right to fair working conditions. Because most of us spend most of our time working, this should matter to all of us. Unfortunately, only a few workers’ rights are specifically enumerated in international documents protecting civil and political rights, such as the right to form and join unions. Other rights are mentioned in treaties dealing with economic and social rights. Some good news on the front of labor rights is that, recently in Europe, workers’ rights advocates have been successful in taking cases to the European Court of Human Rights, which ruled that the right to strike is contained in freedom of association.

In my next blog post, I will write about the broader picture of socioeconomic inequity in Appalachia and the ways in which that disparity has led to human rights failures in the region.

Other References:

- Athey, L. (1990). “The Company Store in Coal Town Culture,” Labor’s Heritage Vol. 2 #1 pp 6-23.

- Savage, L. (1990). Thunder in the Mountains: The West Virginia Mine War, 1920–21. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 978-0-8229-3634-3.

- Podobnik, B. (2008). Global Energy Shifts: Fostering Sustainability in a Turbulent Age. Temple University Press. pp. 40–41. ISBN 9781592138043..

- Rowland, B. (1965) “The Social Order of the Anthracite Region, 1825-1902,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History & Biography Vol. 89 #3 pp. 261-291.