BY: Alesa R. Liles, PhD, MSW

Autonomy within our lives is often something many take for granted. We can make choices for ourselves whether it is a need or want or even a subconscious choice we don’t even think about. This right to choose is a fundamental aspect of humanity.

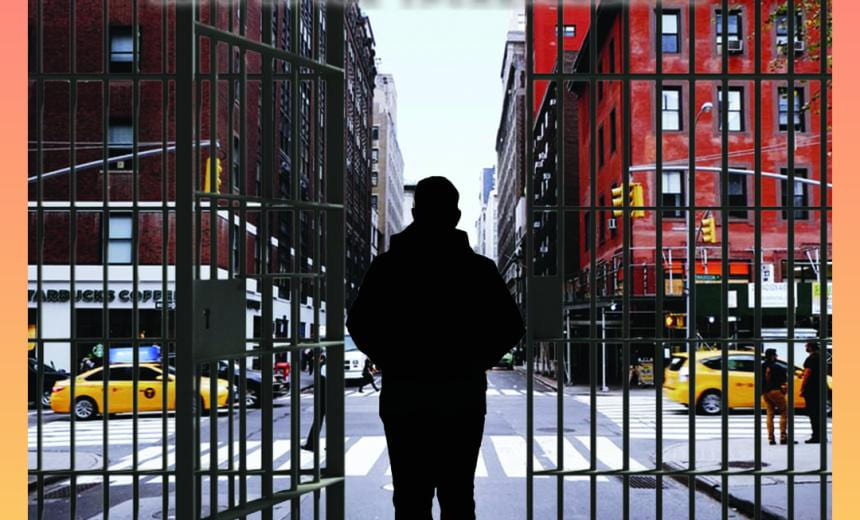

For almost 2 million people incarcerated in the United States, the ability to even make the simplest choices, like when to eat, to shower, to sleep, etc. are extremely limited. Given the penological goals of incarceration, some restriction of freedom is assumed. However, the system of mass incarceration in the United States, not only dictates a person’s everyday life, it systematically dehumanizes and deprives individuals of their inherent dignity. The primary way it does so is through the degradation of one’s identity and human rights. Individuals with little sense of self and little power, who are in the midst of experiencing the trauma of prison life, are easier to control.

As a result of mass incarceration beginning in the 1980s, prisons in the United States have become over-crowded, less safe, poorly managed, and provide few programming opportunities. With the lack of meaningful activities and limited connections to the outside world, individuals are returned to society, inevitably, carrying the trauma of prison home. There are few resources available, such as counselors or therapists, to meet the specific needs of this population in the free-world as well. Because the need for healing remains, the power of storytelling is invaluable in regaining personal dignity and autonomy. The act of storytelling provides an individual an outlet to express their experiences in a safe environment. The individual has autonomy over their personal narrative, ultimately allowing for understanding and healing. Research supports storytelling as one of the most powerful ways for trauma recovery.

To assist citizens returning home from incarceration, creating a platform to tell their story is one way that allows them to regain the dignity and autonomy that was taken. So, in the spring of 2022, my students and I set out to address this issue. We focused on developing a podcast for returning citizens to tell their stories. We wanted to speak with justice impacted individuals about their experiences, particularly their experiences returning to society after significant periods of incarceration. Through the creation of the podcast, we hoped our guests would be empowered to disclose their challenges and successes, and even significant traumas.

As we started the process, we gathered a large amount of research materials to learn more about what incarcerated and formerly incarcerated individuals endure. The statistics were grave. According to a study by the Urban Institute, returning citizens have difficulty finding stable employment, obtaining food, maintaining sobriety, and are often returned to the same neighborhoods with significant socioeconomic disadvantage. Poverty has been identified as the strongest predictor of recidivism. These are the things the data told us, but context is lost in the numbers. People are lost in the numbers.

Identified by a six-digit number for more than 40 years of his life, the first person we spoke to was incarcerated at the age of 18 and released at the age of 62. Charlie spoke about his experiences in prison over 4 decades, what it was like to have children and to lose family while incarcerated, and then being released into a completely different world that have moved on without him. After speaking with us, he stated “prison is a terrible experience that robs a person of self-respect, dignity, and any ray of hope. [This] helped me feel society would accept me.” In providing a platform to speak about their experiences and to tell their stories, returning citizens can reclaim their fundamental rights to dignity and autonomy. By the end of spring, we were able to produce 5 episodes featuring 4 justice impacted individuals.

To the common person, this may sound insignificant, but to individuals who have been stripped of everything down to their name, having an opportunity regain their voice and to see others will listen, is a step forward in the healing process. As stated by Craig Haney with the Urban Institute, “At the very least, prison is painful, and incarcerated persons often suffer long-term consequences from having been subjected to pain, deprivation, and extremely atypical patterns and norms of living and interacting with others.” With more than 95% of incarcerated individuals eventually facing release, healing is surely needed.

Alesa R. Liles is an Associated Professor of Criminal Justice at Georgia College and the Managing Editor of Undergraduate Research. Email: alesa.liles@gcsu.edu