By Lexie Woolums

Sustainability means a lot of things to many different people, and I view that as a positive thing. One part of sustainability that is usually highlighted is the focus on environmental sustainability, given the real-time effects of climate change. Individuals apply this to their lives in many forms, such as my grandmother, who refuses to throw away food, or my supervisor, who walks to the office.

When talking about sustainability, people are quick to bring up things like recycling or electric vehicles (EVs). In essence, this is the low-hanging fruit (not necessarily in price, but they require the smallest amount of effort or change). These are the simple things that make wealthy people feel better about unhealthy consumption habits. This blog is not intended to point fingers. I want to highlight this black-and-white perspective of sustainability, which is misguided. Still, it remains a popular view in much of the Global North due to inadequate education or pure convenience.

In 2024, we would rather feel good about ourselves for putting plastic bottles in the recycling bin than examine why we are still using single-use plastic bottles. For some, these reasons are significant, as not everyone has access to clean and safe drinking water. For others, not so much. The ultimate truth is that it is more convenient to adapt sustainability into our current habits than to change our habits to be more sustainable. Essentially, this view is a type of “convenient sustainability”—or capitalistic sustainability— and is a bit of an oxymoron, considering that capitalism thrives on maximizing profits at the expense of any consideration of long-term social or environmental sustainability.

I am not here to encourage anyone to stop recycling and refuse to buy only gas automobiles but to challenge them to think about it in a less binary way. At a basic level, most of these choices are better for the environment than the alternatives. However, they do not get to the root of the problem, which, for this blog, is a society dominated by a reliance on automobiles rather than on diverse modes of transportation.

Beyond that, the narrative that buying something new will solve climate change is not only false but reinforces the narrative that innovation under capitalism can save us from the repercussions of climate change, which is the same mentality that has gotten us here.

To get to the root of this problem, we must look at different aspects of the life cycle of products to really get at what true sustainability is—not just environmental sustainability but social and economic sustainability, too. In this blog, I will use the case of car overreliance to illustrate true sustainability. Not only is it poor for the environment, but car overreliance also has human rights concerns due to its impacts on air pollution, communities of color, and the global supply chain.

I want to be clear that I do not think it is reasonable to expect us to eradicate the use of automobiles in this country, nor is it necessary. Cars are needed in many rural areas, and the United States is a large country. But in a culture that loves to flaunt the benefits of a free-market system and increasing consumer choice and freedom, why have we accepted that cars are the only option? This acceptance benefits the automobile industry and the fossil fuel industry, even for EVs.

The Rise of the Automobile

It may be difficult to imagine, but automobiles are a relatively new technology, and they are extremely inefficient. The average American automobile spends 95 percent of its life parked, which seems like a crazy statistic at first until you actually think about the amount of time you spend in your car each day.

For the purpose of this blog, I am specifically targeting EVs because they are too often touted as the solution to climate change, especially in the Global North. What I think is most important to note is that this perspective is a privileged one. There are numerous environmental issues that are directly caused by car overreliance, and EVs will not solve most of them.

Pollution, Human Health, and Small Business

The Pew Research Center reports that tires are responsible for 78 percent of microplastics in the ocean. Tires are composed of synthetic rubber that contains over 400 chemicals, including heavy metals such as lead, copper, and zinc—and many of them are carcinogenic. Additionally, the average car with four tires produces 1 trillion ultrafine particles for every kilometer driven (around 0.6 miles).

Automobiles spit out emissions at the street level, which contributes to climate change by releasing carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and hydrofluorocarbons by burning gas and diesel. There is also increasing awareness that automobile exhaust is a public health concern. One 2023 study linked breathing in traffic emissions to increased blood pressure of passengers. Other studies have connected air pollution from automobiles with increased rates of cardiovascular disease, asthma, lung cancer, and death. Additionally, a society focused on cars promotes a sedentary lifestyle, which puts people at risk for many of the same conditions caused by the air pollution from tailpipes.

Moreover, a world built around automobiles (and the rise of the suburb) also benefits large corporations and harms local businesses. Since smaller businesses generally operate in smaller (usually more urban) areas rather than in large commercial lots, car-centric design common throughout the suburbs makes it easier for consumers to purchase from large companies. Meanwhile, many small businesses rely on people walking/passing through, which car dependency negatively impacts.

Urban Sprawl

The rise of the automobile is connected with the rise of the suburbs and modern urban sprawl—think driving down Highway 280 in Birmingham at 5:30 PM on a Tuesday. The rise of the suburbs has increased the number of miles per trip and made it convenient to move far away from the cities. Massive amounts of land were developed, displacing wildlife and allowing the wealthy (and predominantly white) to move away from the cities. Studies have linked development with a decrease in biodiversity. While, arguably, this concerns urban and suburban areas, the suburbs take up significantly more space than urban areas (even though they contain far fewer people living in them).

It is a common misconception to think that a rural home with large, spacious fields is the most “environmentally friendly” way to live, with cities being the enemy of true sustainability, largely due to the historical implications of the Industrial Revolution on cities. While living in a rural area is not necessarily bad for the environment, cities are vastly more efficient from a space perspective, and much of that is because of the diversification of transportation (though this depends on the city).

Much of what I am describing is the ideal end result of success through the American Dream. It focuses on economic prosperity and the goal of owning property and raising a family. It’s no secret that the idea of upward mobility being accessible to all is inaccurate. Aside from that, it can take time before we think about the cost of all of this.

Connection to Human Rights Domestically

Besides the consequences of that for human health we’ve already talked about, overreliance on automobiles exacerbates the already high inequity within the United States. The US Department of Transportation estimates that the construction of the interstate system displaced over 1 million people when it was built starting in the late 1950s. The system was built to connect the United States, and it did, but it connected some groups more than others and came at a high cost to others. The bulk of the interstate system cut through black and brown communities to cater to white commuters who worked in the city but lived in the suburbs. Not only has infrastructure historically cut through communities of color and impacted the once-flourishing social centers there, but by putting a highway there, it places those same groups of people underneath the emissions pipe of people who drive through there every day.

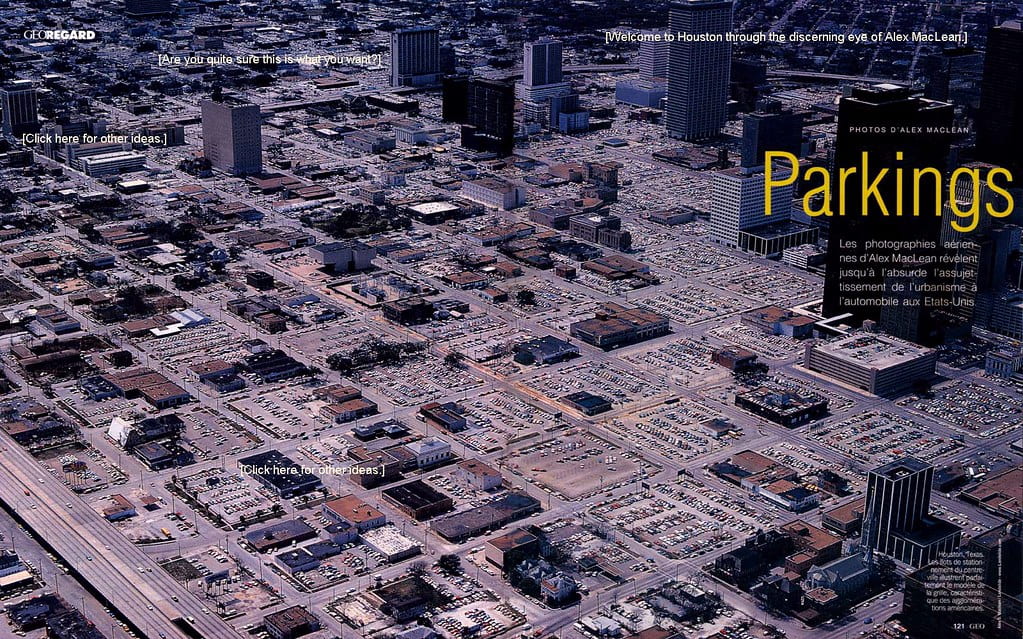

As for the consequences of this shift on cities? There are numerous. One of the main ones that comes to mind is the issue of parking. On UAB’s (University of Alabama at Birmingham) campus, nearly everyone is dissatisfied with the parking situation. This issue goes back to the inefficiency of the automobile. As mentioned earlier, on average, a car is parked for 95 percent of the time, taking up a square of concrete nine feet wide by 18 feet long. This is problematic for urban areas like Birmingham because the density of jobs and people is so high, yet the amount of space is quite tight. It does not take a civil engineer to recognize how inefficient this is in terms of land usage. This is also problematic when you consider that the majority of the time, all the parking lots are empty—yes, they really are empty most of the time.

In addition to their inefficiency, they impact different communities disproportionately. Parking lots are generally built in, near, or even over communities of color, further degrading property values (and can sometimes make those communities warmer due to the heat island effect). This is also concerning for public health because parks in nonwhite areas are generally about half the size of parks in majority-white areas.

When considering all of this, it is not difficult to see how car-centric infrastructure is a human rights issue in the US, often fueled by racist zoning laws and institutions that seek to capitalize on the manipulation of communities of color.

Similarly, the modern American driver is dissatisfied with the amount of traffic whenever “everyone else” is taking up all the room on the road. In the United States, there are large cities that are known to have this problem due to their almost complete reliance on automobiles. Houston and Atlanta are primary examples of this, where they have such high populations and poor public transportation to accommodate the large daily movement of people.

In Alabama and many other states, the solution is to add more lanes, which makes traffic worse due to a concept called induced demand. While it may seem that adding another lane would allow more space for people to drive and reduce traffic, adding another lane to an inefficient system makes the existing system more inefficient. Increasing roads by 10% will temporarily improve traffic, but over time, it will increase traffic by 10%, making the problem worse.

Human Rights Violations in Congo

EVs, as you may have realized, do not solve our parking or traffic problems. Beyond that, there are human rights concerns with the global supply chain that make EVs less ideal, too.

With EVs specifically, the lithium batteries require a significant amount of cobalt. The largest reserves of cobalt in the world come from mines in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Copper is also needed for different types of batteries, including cell phone batteries, and it is frequently mined in Congo as well. Unfortunately, families in Congo have been forcibly evicted due to the opening of new cobalt mines. Amnesty International, a global human rights NGO, has accused large companies who are opening these mines of forced evictions, threats, intimidation, and deception of the people who live there.

It is crucial to mention that ethical considerations like this have long been used by the fossil fuel industry to discredit and slow down the movement toward clean energy. It is imperative for the US to curb emissions and shift towards renewable forms of energy. Additionally, automobiles are a significant component of that, making up the largest category at about 29 percent of GHG emissions in the US. Still, it is critical that we do not continue to uphold unjust forms of labor and oppression. It is precisely these systems that have placed the United States as an economic powerhouse through the exploitation of people from other countries, damaging their health and environmental quality for our benefit.

Moving Forward

From an emissions perspective, EVs are a step in the right direction, but they do not begin to touch most of the other issues discussed in this blog, including environmental racism and public health concerns from an automobile-centered society.

EVs won’t solve the parking problem, the traffic problem, the microplastic problem, or the human rights issues associated with the global suppliers that are notoriously secretive about their practices. While they may decrease direct pollution that is linked with all the health conditions I mentioned earlier, they do not erase the damage to the people and countries that are supplying materials for their construction.

What will start to get at the problem is diversifying transportation. While automobiles are needed in many cases, it is extremely exclusive and inefficient to make them the only option, especially in our mid-size and large cities. In some countries, tax dollars fund all transportation infrastructure rather than almost solely funding infrastructure for cars and requiring bike infrastructure to be paid for by private individuals. In the US, most states spent an average of $1.50 to $3 per capita on bike infrastructure.

Improving public transportation in urban areas and between cities, such as through intercity trains, would benefit public health and the environment. It could also be a small start of changing centuries worth of racism and inequity by decreasing pollution and making it so that the people producing the most pollution cannot drive 40 miles outside the city to get away from it.

Investing in public transportation would also improve the lives of people who cannot drive or do not want to. In a car-dominated society, many disabled people and elderly people are forced to rely on others to take them places or pay for expensive Ubers. Giving them the option to travel without the assistance of others, just like everyone who drives themselves to work, is important to preserve their autonomy so they can maintain control over their own life without relying on others.

Car-centric design favors the wealthy and forces the rest of the population to keep up with car payments and insurance, which are quite expensive for the everyday family. According to the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy, the average American family’s second highest expenditure (behind housing) is transportation, with 93 percent used for car payments and maintenance. It also favors the automobile companies, which is the biggest reason we do not have diversified transportation (like nearly every other developed country).

The simple truth is that the United States economy benefits from the sale of cars, and changing how we view this is difficult. Changing the infrastructure (and, in some ways, creating it) would not be easy, but it would create a more inclusive world. To change this, we must make the best decisions and push for improved public transportation, especially in urban areas like Birmingham.

What can we do?

Realistically, no person can change this system individually, and I think that is a large reason why people love talking about EVs and other ways we can individually make an impact.

Overall, wanting to make a difference is a good thing. It is important to pay attention to the companies you purchase from and ensure they are upholding high ethical and sourcing standards. I have mentioned this in previous blog posts, but the best thing to do is to refrain from purchasing unless you truly need it—and even then, try to buy secondhand.

If you do not need a new phone or laptop, do not buy a new one every year. Remember that companies, including the fossil fuel industry, benefit from the mentality that we should all have the newest thing. This is not good for your wallet, and it is especially harmful for the planet and the humans who collect the resources used in things we take for granted every day.

Another thing to consider is reducing your reliance on batteries. I am not saying to throw out all the batteries you may have at home, but to think of it from a purchasing perspective. It is becoming increasingly common for basic household appliances to be battery-powered because they are convenient. For some people, having multiple battery-powered flashlights for camping is a crucial safety measure, but if you need a new appliance for use in your home, be realistic. Batteries are convenient, but do you really need a battery-powered vacuum cleaner or handheld mixer that could be plugged into the electricity grid for use in a home? Given the questionable industries involved in battery production (and their environmental damage when they are not properly disposed of), eliminating the use of battery-powered objects in cases when they are not necessary is a great start.

A Final Note

I cannot finish this blog without mentioning that Birmingham does have a bus system, but it is mostly designed for people who do not have cars. It is designed as a last resort rather than a first choice, which means that users are often viewed negatively for not having a “better” option.

Arguments against diversifying transportation usually include comments that walking or biking is not accessible because things are so far away.

If that is what comes to mind, I’d like you to consider that most major and even mid-size cities (Birmingham included) had expansive public transportation until private car ownership increased from the 1920s to the 1950s. I cannot include them here, but you can find maps of Birmingham’s old streetcar system online.

Many of the tracks are still here, and we drive over them every day without even realizing it.