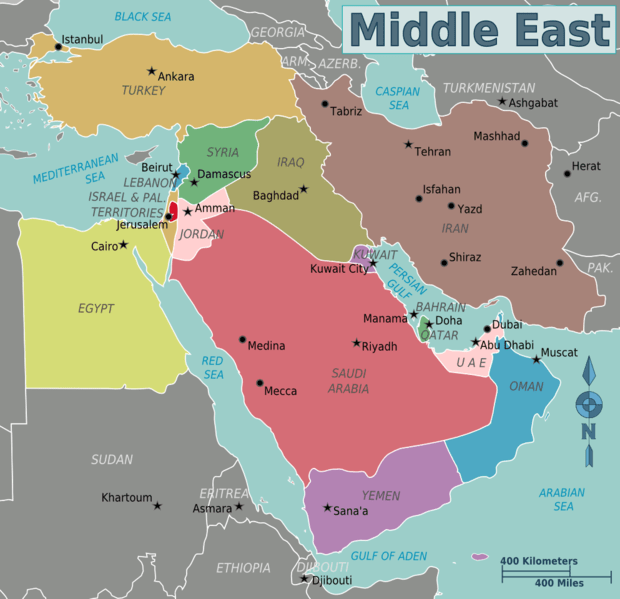

With the increase in world crises, others become forgotten. Seven years and the Yemen Crisis is still one of the worst humanitarian crises in the world. Unnoticed, unseen, and unheard, the cry for help from the suffering in Yemen has been largely forgotten. Yemen has always been the most vulnerable country in the Middle East, even prior to the 2015 Civil War. With the worst rates of malnutrition, more than half of the Yemeni population has been living in poverty with limited to no access to resources need to live. With such an important, detrimentally impactful crisis, why has there been silence surrounding solutions?

Why is there a Crisis?

The Yemen Crisis began with a civil war between the government forces and the Houthis, also known as Ansar Allah. In the past seven years, the residue of the civil war in Yemen continues to worsen tremendously. The conflict has been between the internationally recognized government, backed by the Saudi government, and the Houthi rebels backed by Iran. The war was caused by many factors. Given that Yemen was already one of the poorest Arab countries, any change would cause a political division. These factors include fuel price increasing, the Houthi rebels taking over and causing a military division, and the involvement of Saudi Arabia. Many countries have gotten involved – not to solve the crisis, but to pick the side supporting its agendas and send military equipment and personnel in support of these goals. This has left civilians in grave danger.

Conditions of the Crisis

The country’s humanitarian crisis is said to be among the worst in the world, due to widespread hunger, disease, and attacks on civilians. There have been around 6 million individuals displaced from their homes since the beginning of the catastrophe. There are 4.3 million civilians internally displaced. As of 2021, Yemen had one of the largest numbers of internally displaced people (IDP) in the world. Many IDPs have been living in a constant state of fear and suffering. Being in a state of exile, having insufficient environmental and living conditions, they have no access to the resources needed to survive day to day. In addition, food insecurity, lack of clean water, healthcare, and sanitation services have caused tremendous issues for countless of civilians still living in Yemen.

Women and Children

In the heart of the crisis, the most affected have been found to be women and children. With the state of the country, inflation, along with scarcity of economic opportunities, many families can no longer afford basic meals, leading to high cases of starvation. Further, many cases of gender-based violence, exploitation, and early marriage are on the rise. Malnutrition rates for women and children in Yemen are the highest in the world. About 1.3 million breastfeeding and pregnant mothers are in need of treatment for malnutrition. There have also been found problems with children being forced to fight in the war. In 2019, there were 1,940 children fighting as soldiers.

Mental Health

Mental health in Yemen has deteriorated over the causes and outcomes of the conflict. Individuals have dealt with losing family members and friends, their homes, suffering from displacement, violence due to war, food insecurity, unemployment, diseases, torture…the list can go on and on. With all these factors causing grief then leading to long term depression, individuals in Yemen are not able to seek the proper resources needed. There are about 30 million people living in Yemen in 2020 but only 59 psychiatrists. Meaning, for every half a million, there was only one psychiatrist. With the mental health stigmas already a huge concern in the Middle East, many individuals either do not know they need mental health services or are not allowed to seek them. For instance, women have to ask for permission from their families, particularly their husbands, in order to seek mental health services.

What is the World doing?

The United Nations (UN) has backed and presented peace negotiations, but it has only seen limited progression. The UN found that regional actors involved in the conflict have played a strong role in slowing down the peace process. Observers of the crisis see that the involvement of Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, have prolonged the war and worsened its conditions. The response of the world needs to strengthen when dealing with the Yemen crisis. As we have seen support from the world given to the Ukrainian crisis and the crisis in Afghanistan, as a whole, a change is possible. The most important thing we can do is talk about the crisis. This has gone unheard, but with a collective voice we can urge and find a solution.

What can you do?

The best thing you can do regarding the Yemen crisis is to educate yourself, engage in conversations, and make others aware of what is happening. Below are a list of books and sources to keep you updated in ways you can help.

The World Food Programmee has created a website with ways you can help

Books to Read:

2. Tribes and Politics in Yemen: A History of the Houthi Conflict – Marieke Brandt

3. A History of Modern Yemen – Paul Dresch

4. Yemen Divided: The Story of a Failed State in South Arabia – Noel Brehony