In early November 2018, the United Nations confronted China about the Chinese government’s human rights record since 2013, with UN Member States pointing specifically to China’s suppression of the Tibetan people and for the barbaric ‘re-education camps’ used to indoctrinate the Uyghur Muslims in the Xinjiang province. China flatly denied these allegations, contending they are politically motivated and violate Chinese national sovereignty. While the ongoing conflict regarding Tibet has been covered for decades (you can read an IHR post about it here), the plight of the Uyghur Muslims in China is arguably less familiar to laypersons with vested interests in human rights. This blog post explores the history of the conflict with the Uyghur, how the international community typically handles these kinds of human rights violations, and what everyday citizens can do to help the Uyghur. For another perspective on the plight of the Uyghur, read my colleague Dianna Bai’s post here.

History of the Conflict

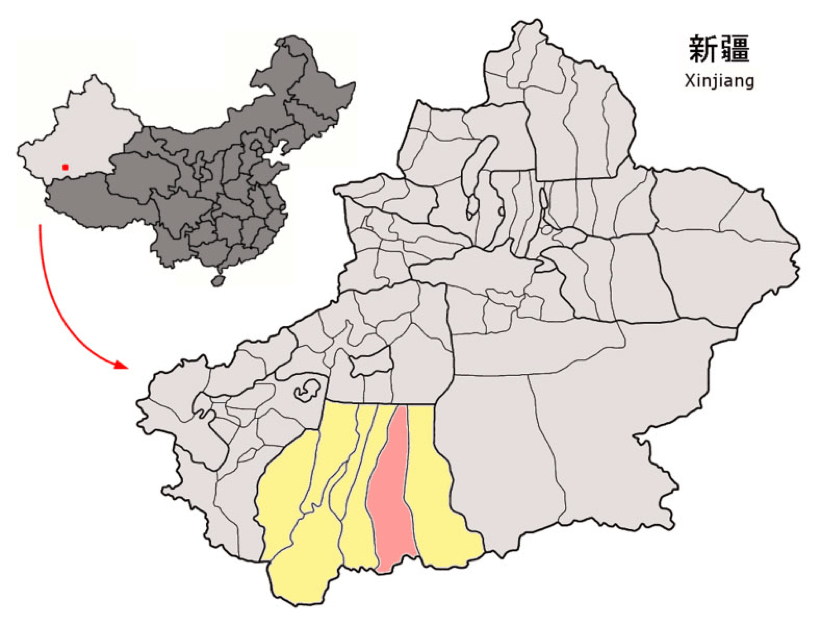

The Uyghur are an ethnically distinct group, hailing originally from the Altai Mountains in Central Asia, now spread through Central and East Asia (Roberts, 2009). Scholars frequently debate the heritage of the Uyghur; government-sanctioned Chinese historians claim the Uyghur are indigenous to the Tarim Basin (located within the Chinese Xinjiang province), while most historical accounts situate the Uyghur as descendants of peoples in modern-day Mongolia (Roberts, 2009). Until recently, many scholars believed that the Soviet Union groomed Uyghur nationalist sentiments during the Cold War, intending to use the fledgling Uyghur people as a colonized Soviet pseudo-nation to exert political and cultural influence in the East Asian theater (Roberts, 2009). This view has since been challenged, as Uyghur Muslims have long defined themselves an ethnically distinct group with the goal of creating their own nation on sovereign territory, intended to be called Uyghurstan (Roberts, 2009). Today, the Uyghur of China largely practice Sunni Islam, speak their own language (similar to Uzbek), and some Uyghur label the territory they inhabit “East Turkestan”, not the Xinjiang providence of China.

The Xinjiang providence, located on the fragments of the ancient Silk Road, is rich in resources and attracted the migration of many Han Chinese to the province (aided and abetted by the Chinese government). This migration brings us to the present day. Beginning in 2009, the Chinese government has cracked down on Uyghur dissidents and rioters expressing a frustrated desire for autonomous rule (some of these Uyghur were subsequently exiled to the United States). In 2016, the Chinese government amped up their approach to the Uyghur, attempting to squash Uyghur cultural practices to create a culturally homogenous Xinjiang province. The Chinese justified these practices by claiming their motivation was to reduce religious extremism in the Xinjiang region. Homogenization efforts included banning baby names (such as Medina, Jihad, and Muhammad) and restricting the length of beards; both aforementioned names and the tradition of long beards stem from the Uyghur’s Islamic faith. These tactics are part of the Chinese government’s “Strike Hard” campaign, designed to specifically monitor the Uyghur situation in Xinjiang. In addition to cultural destruction, the Chinese have recently implemented surveillance programs designed to monitor separatist movements, jihad-ism, or proto-nationalist sentiment. Surveillance programs largely take the shape of indoctrination (or ‘re-education’) camps.

The United Nations has received verifiable reports that up to one million Uyghur (approximately 10-11% of the adult Muslim population in the region) are currently held against their will in these re-education camps. The Chinese government, however, claims these are vocational centres, designed to empower the ethnic Uyghur to learn the Chinese language, Chinese law and ideology, and gain workplace skills. Dilxat Raxit, spokesman for the World Uyghur Congress (more on the WUC later), has publicly decried the camps, as they incessantly monitor Uyghur prisoners through sophisticated facial recognition software, designed with the intention to predict individual or communal acts of protest through the analysis of the prisoners’ micro-expressions (and no, the current year is not 1984). The prisoners in these camps are expected to ‘secularize’ and ‘modernize’; the Chinese government conditions the entrapped Uyghur Muslims by forcing the prisoners to wish Chinese President Xi Jinping ‘good health’ before the prisoners are given food, thank the Chinese government and Communist Party, and renounce devotion to the Islamic faith. Furthermore, Uyghur Muslims have been forced to eat pork and drink alcohol during their imprisonment which, for many devout Muslims, is forbidden by the Islamic faith. One escapee who found asylum in Kazakhstan testified that she “worked at a prison in the mountains” in Xinjiang and was forced to teach Chinese history during her imprisonment.

The Chinese government has not limited its repression to these detention centers. Beginning in 2016, Uyghur Muslim communities in the Xinjiang province have been subjected to China’s “Becoming Family” initiative (also directed by the government’s “Strike Hard” campaign). The Chinese government mandates ‘home stays’ (lasting between five days and up to two months) within these communities, dispatching over one million cadres to closely monitor the private homesteads of the Uyghur communities. These cadres monitor ‘problematic behavior’ such as suspected alcoholism, no alcohol consumption whatsoever (a sign the family is devout Muslim), uncleanliness, and other signs that the Uyghur are becoming ‘too Muslim’ for the secular Chinese government. Finally, these cadres are tasked to promote ‘ethnic unity’ in the region, spouting the dangers of Islamism, pan-Turkism, and so on. These spies of the state document every move of the Uyghur communities, reporting intelligence back to the Chinese government, who then specifically targets individuals and families suspected of dissident behavior. It is impossible to track how many ‘dissidents’ (whether in their home communities or in the Uyghur detention centers) have been murdered by the Chinese government. A prominent Uyghur human rights activist recently lamented,

This begs the question: how do human rights organizations (from the United Nations to the Institute for Human Rights) classify this level of social, cultural, and civil repression? And furthermore, how can human rights organizations utilize this classification to mobilize aid for the Uyghur Muslims?

Addressing Crimes Against Humanity

The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, Article 7, broadly characterizes Crimes Against Humanity (CAH) as:

any of the following acts when committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population, with knowledge of the attack:

- Murder;

- Extermination;

- Enslavement;

- Deportation or forcible transfer of population;

- Imprisonment or other sever deprivation of physical liberty in violation of fundamental rules of international law;

- Torture;

- Rape, sexual slavery, enforced prostitution, forced pregnancy, enforced sterilization, or any other form of sexual violence of comparable gravity;

- Persecution against any identifiable group or collectivity on political, racial, national, ethnic, cultural, religious, gender as defined in paragraph 3, or other grounds that are universally recognized as impermissible under international law, in connection with any act referred to in this paragraph or any crime within the jurisdiction of the Court;

- Enforced disappearance of persons;

- The crime of apartheid;

- Other inhumane acts of a similar character intentionally causing great suffering, or serious injury to body or to mental or physical health.

In theory, the plight of the Uyghur Muslims certainly falls within this definition, as the Chinese government is violating parameters 1, 3, 5, 6, 8, 9, and 11 of the Rome Statute. Again, in theory, this means the international community has an obligation to both classify this as a CAH and prosecute both the Chinese government as a whole and individual officials directly responsible for the repression of Uyghur Muslims. In practice, however, formally prosecuting CAH are tricky.

To prosecute CAH, a step towards retributive justice, one of two forms of jurisdiction must apply: the state must either (a) be a member to the Rome Statute / International Criminal Court (ICC); or (b) the case is referred to the ICC Prosecutor by the United Nations Security Council (UNSC). In this case, China is not a State Party to the Rome Statute, so requirement (a) is out. Regarding requirement (b), the UNSC can indeed refer this to the ICC Prosecutor. However, since China is a permanent member of the UNSC with full veto power, it seems extremely unlikely the Chinese government would permit a prosecution against its own state. So what options are left for the international community to protect the Uyghur Muslims and hold their repressors to justice for this ‘unofficial’ Crime Against Humanity?

If the international community suspects a state conducts COH, accusatory states may take indirect action to punish the offender state. Here’s one example of such indirect action: US Senators Rubio (R-FL) and Menendez (D-NJ) and US House Representatives Smith (R-NJ) and Suozzi (D-NY) are set to introduce legislation to US Congress proposing (a) the creation of a State Department role to monitor the persecution of Uyghur Muslims; and (b) the Secretary of Commerce enact sanctions to state agents in the Xinjiang province. Indirect action, whether government-led sanctions or non-governmental tactics (e.g. ‘naming and shaming’), aims to overcome the absence of international legal precedent in circumstances such as these (Franklin, 2015). The endgame of indirect action in circumstances such as these is to either offer an incentive for states to cease CAH or increasingly layer punishments (whether economic or otherwise) to render the CAH more trouble than it’s worth. In this case, the ideal outcome for US Congress members is that the threat of economic sanctions would punish the Chinese, forcing the state to choose economic growth as a higher-ranking priority than repressing the Uyghur.

A final alternative to addressing CAH is that of truth and reconciliation commissions (TRC; Landsman, 1997). TRC’s are structured around the idea of restorative justice, meaning that in the wake of CAH, damaged communities themselves work with the international community to: (a) collect ‘facts-on-the-ground’ about ongoing repression, (b) negotiate with the repressing state to end the CAH, and (c) devise solutions to repair the trauma caused by the CAH (Longmont Community Justice Partnership, 2017). This is a human-driven approach, placing the victims themselves at the center of the process to document, cease, and heal from CAH. In the this case, this would mean international NGO’s would connect with local Uyghur Muslims in the Xinjiang Province; document the short-, intermediate-, and long-term needs of the afflicted communities; and allow this joint collaboration to drive local and international efforts attempting to bring the CAH to a close.

Justice(s) for the Uyghur

Resolving the plight of the Uyghur is a highly complex issue. Formal legal mechanisms, such as referring this case to the International Criminal Court, are constrained by the structure of international governing bodies. Indirect action, such economic sanctions proposed by members within the US Congress, have historically had a low success rate (~34% rate of success) to compel policy change (Pape, 1997). Finally, truth and reconciliation commissions have been criticized for their toothlessness regarding holding human rights violators responsible for their crimes (Van Zyl, 1999). What, then, can we do?

The World Uyghur Congress (WUC), whose president Dolkun Isa is an exiled Uyghur Muslim, is taking a hybrid approach to seeking justice for the Uyghur. The WUC’s platform combines the three previously discussed approaches (retributive justice, economic sanctions, and restorative justice), channeling their efforts into international governance, state-level policy and advocacy, and community-driven capacity building. The WUC, steered by survivors of the conflict themselves, aims to achieve justice(s) for the Uyghur people, through a multi-lateral and multi-level approach. While many of their efforts are aimed at high-level government officials and advocacy networks, the WUC additionally aims to engage, educate, and empower ordinary citizens (like you, the reader) to make meaningful contributions towards ending the repression of the Uyghur, ranging from advocacy training to planning peaceful protests. The WUC (and other innovative NGOs addressing other global human rights violations) understands that it is not only the United Nations and its member states that can end human rights violations. Ordinary citizens themselves must take up the mantle of protecting human rights when the hands of the international community are tied. Creating justice for crimes against humanity is the responsibility of all global citizens – and here’s what you can do to help.

References

Franklin, J. C. (2015). “Human rights naming and shaming: International and domestic processes” in H. R. Friman (Ed.) The Politics of Leverage in International Relations. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Landsman, S. (1997). Alternative responses to serious human rights abuses: Of prosecution and truth commissions. Law and Contemporary Problems, 59(4), 81-92.

Longmont Community Justice Partnership (2017). Restorative Conversations and Agreement: Structured Conversations for Resolving One-on-One Conflict. https://boulderhousingcoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Restorative-Conversations-and-Agreement-Meetings-for-BHC-Manual.pdf

Pape, R. A. (1997). Why economic sanctions do not work. International Security, 22(2), 90-136.

Roberts, S. R. (2009). Imagining Uyghurstan: Re-evaluating the birth of the modern Uyghur nation. Central Asian Survey, 28(4), 361-381.

Van Zyl, P. (1999). Dilemmas of transitional justice: The case of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Journal of International Affairs, 53(2), 647-667.