Introduction

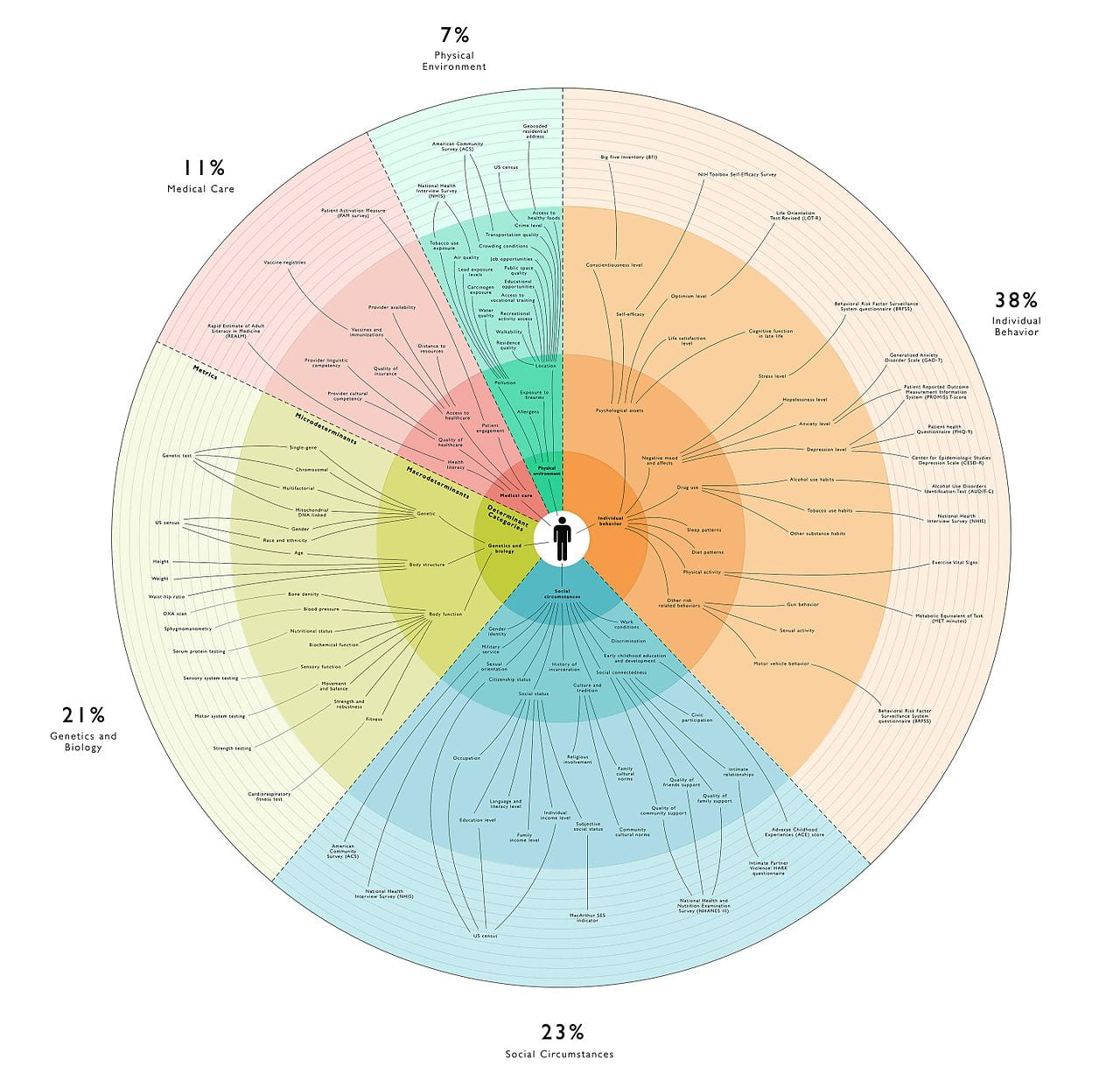

The field of medical anthropology is charged with exploring how cultures determine health outcomes and how health determines culture within a given population. Culture is here defined here as the continuous process by which humans create and communicate shared values, customs, and knowledge within a society; health is here defined as the state and process by which an individual promotes well-being and quality of life. Medical anthropology is especially interested in marginalized populations, exploring how these groups both suffer from health disparities and overcome these disparities through culturally-particular sources of resilience and strength. At the core of medical anthropology’s exploration is the concept of our three ‘bodies’: (1) our physical body, i.e. the body of lived experiences; (2) our social body, i.e. how culture symbolizes and represents our personhood; and finally (3) our body politic, i.e. how our bodies are regulated, surveilled, and controlled over our lifetime (Scheper-Hughes & Lock, 1987). Individuals suffering from any form of violence (direct, indirect, and / or structural) typically suffer worse health outcomes, unless other protective factors (e.g. resilience, medical intervention) can transform this violence.

Of particular importance within the American ‘health culture’ is that of black bodies – how Americans of African descent suffer from higher rates of diseases, illnesses, and sicknesses than their counterparts from European descent. This health-based intersection of nationality, ethnicity, and violence is not only a concern of medical anthropologists – many other academic disciplines are working hard to predict, control, and prevent health disparities within Americans of African descent. For example, I currently manage a health and clinical psychology laboratory at UAB under the direction of UAB Psychology professor Dr. Bulent Turan. Our lab explores the biopsychosocial burden of stigma on health outcomes in African American populations. The question of how culture enacts stress, trauma, and negative health outcomes in minority populations, and how to prevent this from happening in the future, is a huge task – first undertaken by medical anthropology, now including diverse fields such as health psychology, public health, neuroscience, peace and conflict studies, and medical sociology. In honor of Black History Month, this blog post explores how cultural prejudice and hate quietly kills Americans of African descent.

Allostasis and Structural Violence

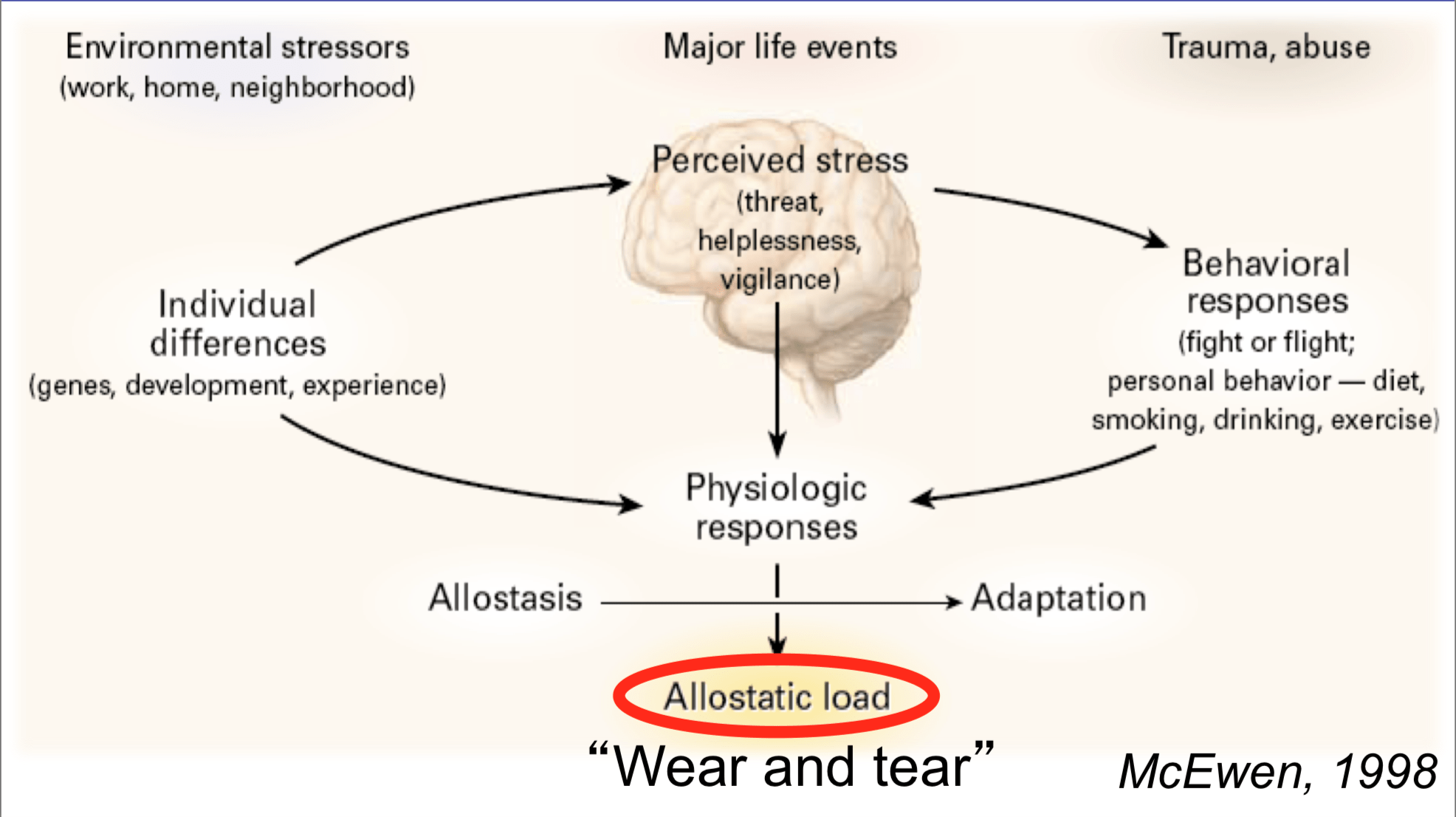

One of the most prominent and empirically-validated theories to explore the relation between culture and health is that of allostasis, first proposed by Drs. Peter Sterling (a neuro-biologist) and Joseph Eyer (an epidemiologist) in 1988. These scientists and their research team sought to explain how stressful life events impact an individual’s health, first drawing on Walter B. Cannon’s famous dictum of homeostasis– the idea that our bodies attempt to ‘correct’ itself in response a changing environment. Homeostasis explains why, when you step outside on a cold day, that your body begins to sweat to cool you down. However, Sterling and Eyer ran into an obstacle with homeostasis. Individuals react widely differently to physiological stress, and Cannon was unable to explain why this might be the case. Sterling and Eyer proposed that stress over the lifetime creates ‘wear and tear’ within our bodies – higher amounts of stress (for example, chronic stress resulting from racial discrimination) create a higher allostatic load(AL). High allostatic load, according to Sterling and Eyer’s research, results in symptoms including:

- High blood pressure / hypertension

- High levels of fatty deposits in our blood stream

- Blood clotting

- Atherosclerosis (hardening and narrowing of arteries)

- Suppression of our immune response system

- High demands of oxygen by our heart

- Having a stroke

- Congestive heart failure / heart attack

Allostatic theory (and subsequent empirical support) is quick to add that not all stress is damaging to an individual – eustressoccurs when challenging life events actually make us stronger (for example, the stress your body endures during a challenging workout at the gym). However, chronic and unpredictable stressors are embodied and produce the aforementioned health concerns (this kind of stress is called distress). Therefore, it may be assumed that individuals at a high risk of distress over the lifetime are placed at high risk for negative health outcomes, ranging from momentary physiological arousal to premature death.

A primary driver of chronic, unpredictable distress is structural violence, defined by Galtung (1969) as cultural inequalities (especially lack of access to power) preventing individuals from reaching their full potential. Structural violence is often difficult to pinpoint because there is no one culprit – no one person is responsible for unequal access to healthcare for Americans of African descent; our social system itself is configured to place minorities at a greater risk for distress and lower health outcomes. Farmer (2004) correctly locates several insidious causes for structural violence across cultures, citing historical factors, political forces, latent racism and other forms of unconscious bias, and economic orders as a few examples.

To summarize, here are the takeaways of the complex relation between allostatic theory and structural violence:

- Vulnerable populations have unequal access to power within a society.

- These populations experience distress due to this unequal access.

- Chronic distress manifests in the physical bodies of these populations, leading to high allostatic load.

- High allostatic load results in health disparities.

- These health disparities go unaddressed due to unequal access.

While indeed tautological, this feedback loop illuminates the vicious cycle many Americans of African descent embody – bodies unjustly assailed and structures unfairly positioned.

Black Bodies & Intervention

As previously mentioned, many medical anthropologists conceive of three ‘bodies’ of health: physical, social, and political. The relative health of these bodies acts on one another; it is therefore paramount to address health promotion in a holistic fashion – not only ‘curing the disease’ but also disarming cultural forces that predisposed disease in the first place. Below, I organize threats to and interventions for health in Americans of African descent, according to their physical, social, and political bodies.

Physical

Physical bodies are the stuff of muscles, of skin, of blood. For Americans of African descent, population-level physical health and wellbeing is simply incomparable to Americans of European descent in major ways, including: higher rates of diabetes; of hypertension; of coronary heart disease; of cardiovascular disease; of prostate, lung, and breast cancer; and of asthma-related death. Furthermore, American adolescents of African descent suffer disproportionally from sexually transmitted infections. The infant mortality rate of these Americans is approximately three times higher than infants born to American mothers of European descent. Geronimus, Hicken, Keene, and Bound (2006) demonstrated Americans of African descent experience higher allostatic load than other Americans, controlling for demographic variables, such as education and poverty levels.

According to a systematic review by Crook et al. (2009), there are a few promising avenues for intervention to address physical health in Americans of African descent. These include placing health centers within communities of marginalized populations, using trained volunteer community health workers, and hiring nurses from within the communities of these populations. Additionally, ‘traditional’ healthcare settings (i.e. hospitals) are not necessary to delivery physical health interventions; these interventions can be administered in community centers. Of critical importance here is self-representation – members of marginalized communities empathize with and deliver quality care to members of other marginalized communities.

Social

Our social bodies are reflective of cultural norms, symbols, and values. This body may be conceived of as psychosocial experiences. Our social body is maintained by the attitudes other people have about us. In the case of Americans from African descent, bias, prejudice, and discrimination oftentimes characterize their social body. Clinical-community psychologist Dr. Lyubansky of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, is quick to assert that this phenomena looks like “racism not always by racists”. In line with allostatic theory, chronic and unpredictable experiences with bias and discrimination induces stress; which, again, causes stress and disease.

Dr. Janice Gassam, applied organizational psychologist, draws on scientific and popular literature relating to social stigma and discrimination and recently published a short guide to disarming unconscious bias. First, we must be aware of our biases; one way to do this is by taking Harvard’s Implicit Association Test. Next, members of majority or privileged populations must make a long-term commitment to reducing bias; this phenomenon will not happen overnight. Next, specific behaviors related to bias must be neutralized; this includes unfair hiring practices and medical maltreatment. Finally, Dr. Gassam asserts that teamwork with members of minority populations can fundamentally disarm cultural bias – evidenced by Edward B. Tichener’s and others’ research on the Mere Exposure Effect.

Political

Finally, the body politic refers to the relation of an individual and her or his political milieu, specifically how the human body is a political tool. The relation is bidirectional as it relates to health and medicine: bodies are both governed by political decisions while also exerting power over the political process. Some bodies (and their corresponding health or otherwise) are prioritized within a political system; other bodies are ignored or violated. A striking example of the violation of political bodies in American culture is voter suppression; we may look to the recent Georgia gubernatorial election and the myriad audacious tactics to keep Americans of African descent out of the voting booth. If individuals cannot vote for policies that may benefit their physical and social health, these individuals do not have political health.

Within the context of the United States of America, voting behavior is the primary way disenfranchised individuals exert political control; it is therefore paramount to empower minority voters so these individuals may elect leaders dedicated to championing causes related to health promotion within marginalized communities. The think-tank Center for American Progress offers five ways to protect the votes of Americans of African descent: (1) eliminate strict voter ID laws; (2) prevent unnecessary poll closures; (3) prohibit harmful voter purges; (4) prioritize African American voters in political outreach; and especially (5) recruit African American candidates for political office. Marginalized Americans must be able to vote for policies and representatives that can break the health disparity cycle.

Conclusion

Observing, predicting, preventing, and controlling health disparities within marginalized populations is an immensely complex issue. As stated in the beginning of this post, medical anthropologists take a cultural standpoint to examine these issues; one prominent theory in this discipline is the systematic examination of ‘bodies’ – how these bodies are affected by health and disease alike. Other fields, such as health psychology, take a more empirical approach – locating specific points of intervention within an individual’s biopsychosocial health processes. This post combines these approaches, explaining how health deficits arise within the communities of Americans of African descent, utilizing allostatic theory and structural violence. To reduce these health disparities, chronic stressors and structural barriers plaguing these communities must be transformed. This transformation begins by accepting a simple fact about black health: the stress from hate can kill you.

References

Crook, E. D., Bryan, N. B., Hanks, R., Slagle, M. L., Morris, C. G., Ross, M. C., Torres, H. M., Williams, R. C., Voelkel, C., Walker, S. & Arrieta, M. I. (2009). A review of interventions to reduce disparities in cardiovascular disease in African Americans. Ethnicity & Disease, 19(2), 204-208.

Farmer, P. (2004). An anthropology of structural violence. Current Anthropology, 45(3), 305-325.

Galtung, H. (1969). Violence, peace, and peace research. Journal of Peace Research, 6(3), 167-191.

Geronimus, A. T., Hicken, M., Keene, D. & Bound, J. (2006). “Weathering” and age patterns of allostatic load scores among black and whites in the United States.American Journal of Public Health, 96(5), 826-833.

Scheper-Hughes, N. & Lock, M. M. (1987). The mindful body: A prolegomenon to future work in medical anthropology. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 1(1), 6-41.

Sterling, P. & Eyer, J. (1988). “Allostasis: A new paradigm to explain arousal pathology” in S. Fisher and J. Reason (Eds.) Handbook of Life Stress, Cognition and Health. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.