On Thursday, October 18th, an event titled How Germany Has Come to Terms With Its Past was held at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute. The evening began with a lecture by former German diplomat Stefan Schlüeter who discussed how Germany has addressed its notorious role in World War II. Following, Schlüeter participated in a panel discussion with Laura Anderson (Alabama Humanities Foundation), Kiara Boone (Equal Justice Initiative) and Gregory Wilson (History Instructor at Lawson State Community College), putting this topic in the context of United States history.

Stefan opened by claiming there was silence in Germany after World War II, likely due to embarrassment and shame of the Nazi regime. Nevertheless, Schlüeter insisted we must keep the memory alive and never forget the millions who lost their lives during the Holocaust. Although there is an obvious presence of the country’s past, since the 1960s, German students have learned about the Third Reich in which he explained the teaching style and age of the student can mold how one processes this information; therefore, it is pivotal how one is taught. Such attempts to highlight and critique bigotry are a work in progress as we’ve clearly witnessed a resurgence of populism throughout Europe and North America.

The subsequent panel discussion centered on three main questions: How do we talk about the past? Who owns the past? How do we come to terms with the past? As a result of Birmingham’s legacy in the Civil Rights Movement, the discussion largely addressed the history of slavery and Jim Crow laws in the United States.

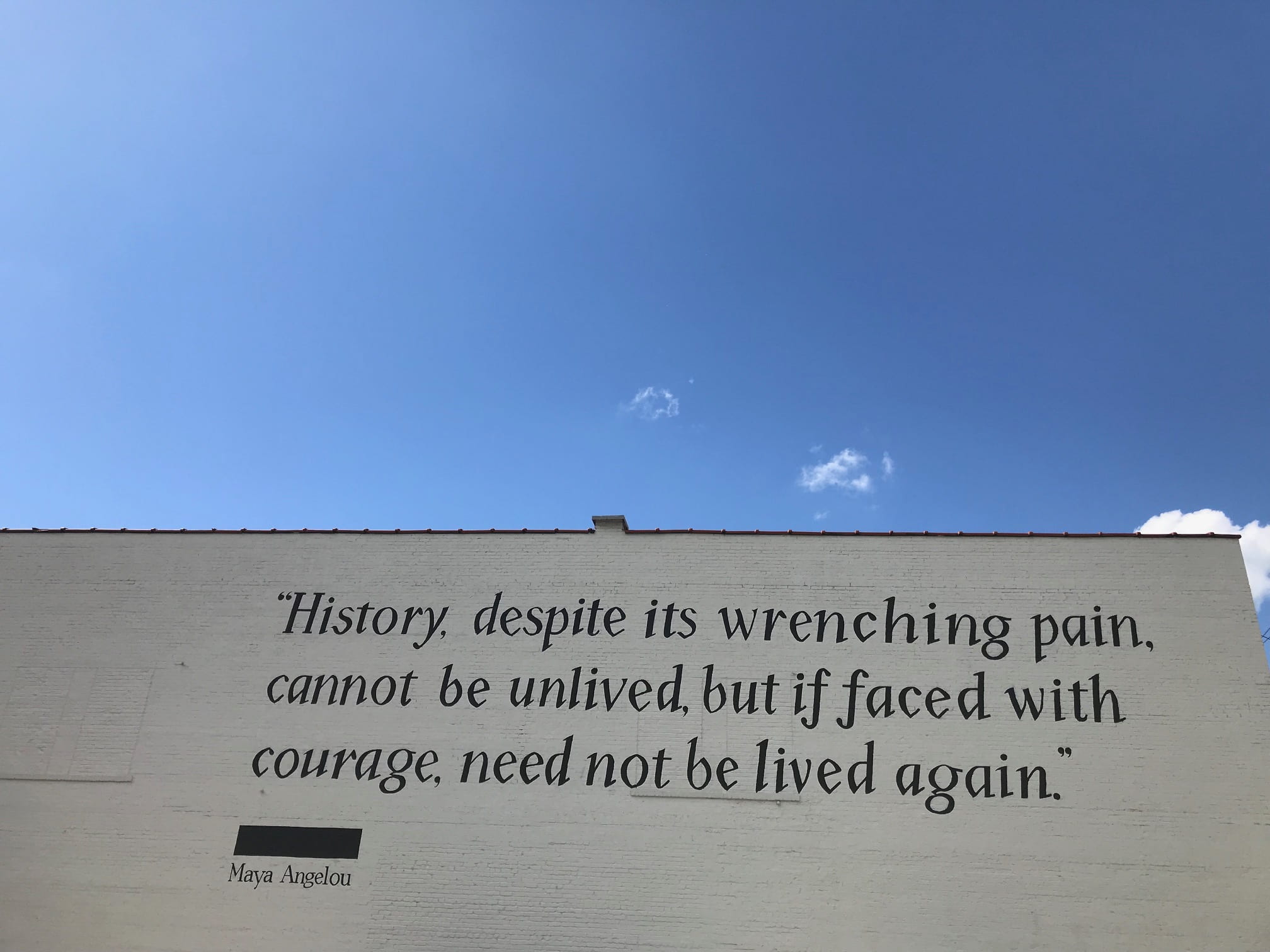

The discussion began by addressing how Americans are forgetting about controversial moments in history such as the Holocaust and Civil Rights Movement. This generated discussion about the possibility of mandating education of these histories, to ensure such events are never forgotten or to occur again. Wilson explained how he takes his students to museums, so they can view archives and artifact preservation behind the scenes, giving history a tangible presence. The panel then suggested there are holes in history and how bridging them with more information can cultivate nuanced discussion.

As for memorials, such as The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, it was suggested they be accompanied by information about the events as well as add individual narratives to the numbers of those who experienced oppression. The use of storytelling puts a face to a story, such as Harriet Tubman, and is better suited to resonate with audiences. Although, we can’t just change laws that mandate education, we need to change heart and minds of those who might carry attitudes that reflect the past.

When discussion centered on who owns the past, the panel demonstrated mixed feelings. It was argued that because we are all linked to history, we all own it. However, it was also demonstrated how depictions of history are predicated on power, leading to critiques of about Civil Rights education such as the lack of teaching around activist tactics and methods of the opposition. Such critiques beg us to further investigate these events and amplify the voices of people missing from these histories.

Following the panel discussion, audience members contributed to the discussion with their own questions such as: To what extent should Civil Rights education be focused on shock value? How do we integrate the legacy of colonialism into these teachings? What does it mean to be a good ally? Ultimately, dignifying these questions not only give us a more informed, honest account of history but also ensures those who need their voices heard the most are afforded their agency and liberation.