A video of a slave trade in Libya presently circulates the international circuit, eliciting pleas from the international community to the UN, and the UN Security Council to Libyan government to do something to end the “heinous abuses of human rights.” Questions of the video’s validity arose when Libyan officials, based on President Trump’s go-to slogan, discredited the report as “fake news” because it is a product of a CNN investigation. However, in April, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) exposed the slave markets after staff based in Niger and Libya gathered testimonies of these markets. The trafficked individuals are migrants from Nigeria, Ghana, and Gambia seeking passage through Libya to Europe. “Migrants who go to Libya while trying to get to Europe have no idea of the torture archipelago that awaits them just over the border. There they become commodities to be bought, sold, and discarded when they have no more value.” In other words, the video confirms what the humanity already knows: human beings are trafficked and disposed of by other human beings. The Palermo Protocol defines trafficking in persons is an all-encompassing term for the recruitment, transportation, transfer, and exploitation of another for the purposes of commercial sex exploitation, labor trafficking, and organ trafficking. This blog focuses on labor trafficking, which includes domestic/manual forced migrant labor, and speaks to three issues surrounding this labor trafficking case: the international attention, the commonplaceness, and the international complicity.

The rawness of the video, in many ways, conjures images of American colonial and antebellum days gone by—when Africans were sold in markets and public squares to the highest bidder, thereby becoming property and labor on soil that was not their own. Given the fact slavery in the United States occurred nearly 400 years ago, why is this scene garnering international attention and creating a stir? First, the video provides undeniable evidence of the dehumanizing condition of slavery and the audacity of traffickers and traders. Second, it is a stack reminder that slavery, despite the Emancipation Proclamation in the US, never ended in many other regions of the world, including Libya. Lastly, it is challenges the notion of who is valuable and worth saving, and who civil society may continue to turn its back on.

It is essential to distinguish between indentured servitude and slavery. An indentured servant enters into an agreement with full acknowledgment of unpaid labor for a fixed and agreed-upon timeframe. William Mathews voluntarily made himself the servant of Thomas Windover in 1718 for the period of seven years. For his part, Windover agreed to teach, feed, clothe, and provide lodging to Mathews, who upon his release would receive “a sufficient new suit of apparel, four shirts, and two necklets [scarves].” Slavery, on the other hand, was and is about exploitation and “every sort of injustice…and debasement.” The written account of Olaudah Equiano and his family describes the feelings of betrayal and disillusionment of being “torn from our country and friends to toil for your luxury and lust of gain… Surely this is a new refinement in cruelty”. The essential difference here is the presence or absence of choice.

Choice is the thin line separating the inferior from superior, poverty and enough, and animals and human beings. Choice, whether from individual, societal, or government level–influences how we perceive. Bales, in his book, Disposable People: New Slavery in the Global Economy, offers two views of slavery: old and new. Both possess a dehumanizing element. However, old slavery prided itself on ownership and maintenance of “property”; new slavery focuses on bodies for profits. Ownership takes a backseat to the profit margin. This new slavery relies on the disposability of human beings. This reliance enables Bales to assert slavery never ended; it simply evolved. Slavery, at its core, is the theft of life. The theft of one life indirectly affects another.

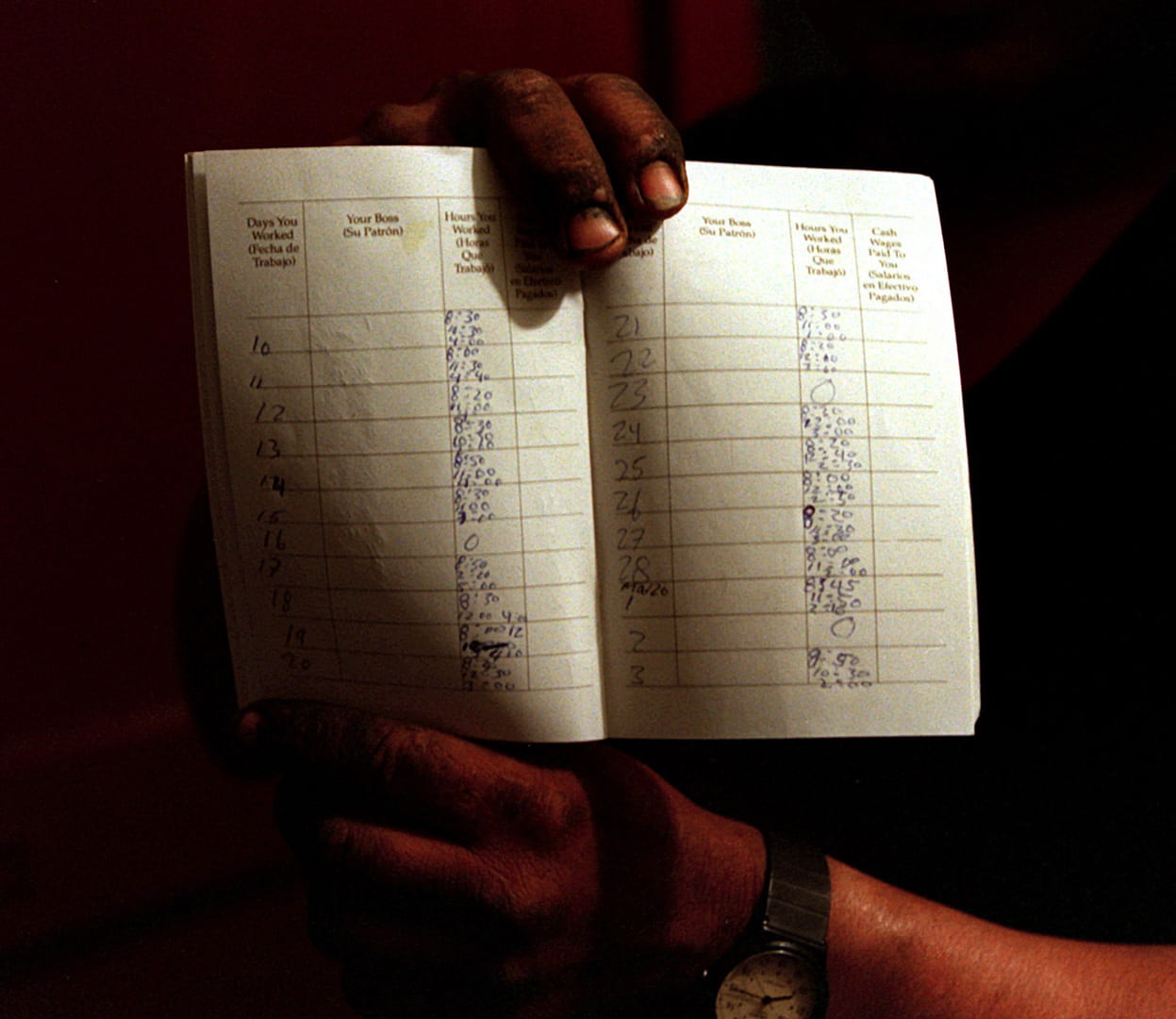

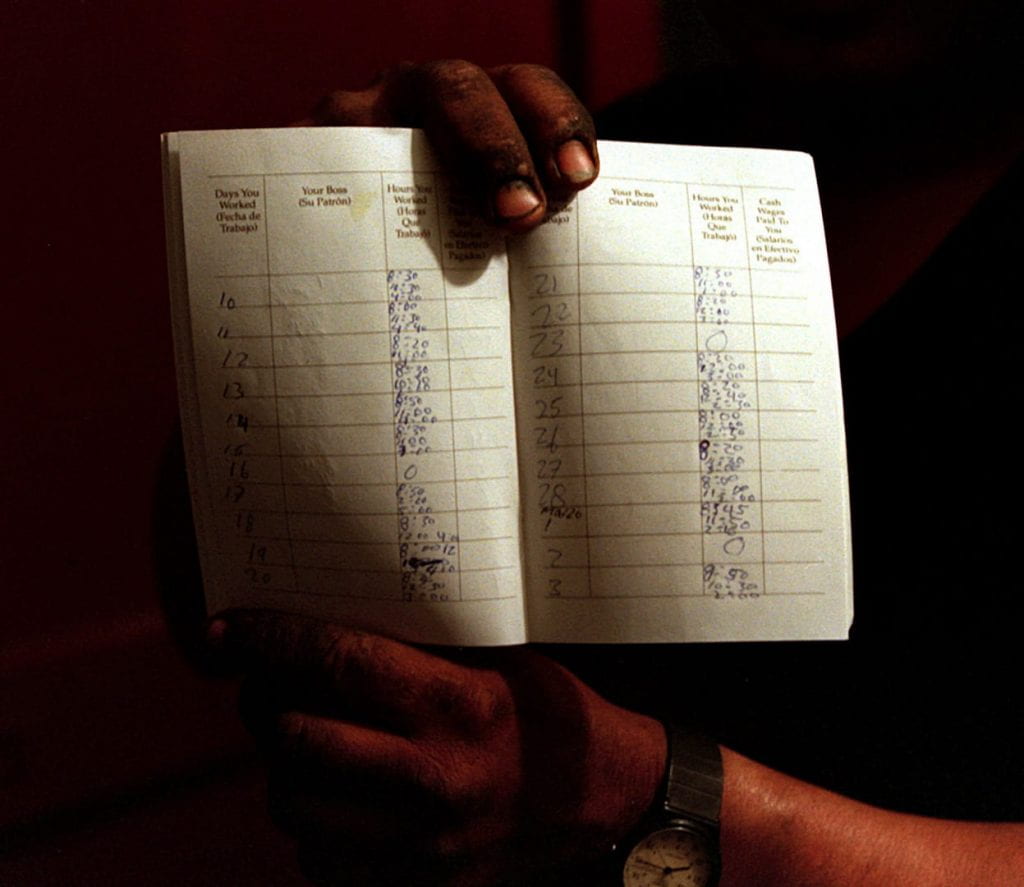

Traffickers sell sex slaves on the black market, underground, and on the dark web. Bonded labor is often intergenerational in places like Pakistan and India, thus, children oftentimes are born into slavery. Migrant workers build soccer stadiums in Qatar and Brazil for FIFA World Cup and the Olympics, respectively, after fleeing poverty in their home countries. Unpaid or slightly paid workers, specifically children, sew garments for major fashion brands, grind coffee beans for industry leaders, and pick cocoa beans for chocolate bars sold in America. The major issue with labor trafficking lies in the complexity of the supply and demand chain, and the complicity of local and national government officials.

Per Free the Slaves website, of the estimated 40 million enslaved persons worldwide, 50% are forced laborers. ABC used last spring’s television show, American Crime, to bring some aspects of labor trafficking to light. The mini-series revealed the interconnectedness of an American tomato farming family and the illegal migrants they employed. In a poignant scene, a fire conflagrates the property, killing several enslaved workers trapped inside. A real-life similar incident occurred in July 2017, whereby nine migrants died in a semi-trailer at a San Antonio Walmart. Many quickly jump to the assertion that ‘they should have done it the legal way’ and ‘they are taking away American jobs’ or ‘should not seek refuge in the EU’, yet what often happens is we fail to examine the backstory and interconnections.

Libyan Arab Spring occurred in February 2011. The death of leader Colonel Muammar Gaddaffi in October 2011 by NATO forces left a vacuum for the rise of the Islamic State. Several failed attempts for parliamentary elections, crumbling infrastructure, thousands of internally displaced citizens (IDPs), and limited resources coalesce to create the perfect storm for the rise and perpetuation of trafficking in persons. Additionally, continental intrastate conflicts and civil unrest result in large migrations of IDPs and refugees desperate for a semblance of normalcy and peace. The proclivity of new slavery, unlike old slavery, is not race or religion but on “weakness, gullibility, and deprivation”. Put another way, the subjection of the trafficked is the misapplication of trust in an uncontrolled situation. Nikki Haley, in the 2017 TIPS Report, concludes that the impact of trafficking in persons is cross-cultural, leaving no country “immune from this crisis.” The slave markets of Libya are not the first occurrence and they will not be the last; however, the video makes them known.

After a month of awareness and contained outrage, where do we sit on the elimination of slave markets in Libya, specifically? The UN released a statement condemning the markets while noting Libyans have launched an investigation, and encouraging inter-regional cooperation. Amnesty International (AI) named and shamed EU governments–particularly Italy—for their collusion and complicity in creating and maintaining a system of abuse. AI discloses the three-pronged policy of containment consists of provision of assistance to run detention centers, coordination with Libyan Coast Guard to intercept and return fleeing refugees, and cooperation with leaders on the ground to halt the smuggling of seekers by increasing border controls. The Italian government, a state party to the Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and its protocol, pays to refuse refugees and asylum seekers and knowingly returns them to a foreign land for detention and torture. Libya is not a state party; therefore, signing the Convention and implementing asylum law as suggested by Dalhuisen will constitute a step in the right direction, when Libya establishes a functioning government.

The fight to end human trafficking is a global civil society (GCS) responsibility. Glasius believes GCS is a voluntary, social contract based association with others who desire to reach and include humanity to think and participate in the world as global citizens, not simply national citizens. How can one participate in GCS? First, employing social media platforms as advocacy tools. Second, reading the TIPS report and following international entities like the UN and AI will keep you informed of changes in international government strategies and shortcomings for prosecution, protection, and prevention of human trafficking. Third, shop and buy products that are fair trade by understanding the relationship between the supply and demand. Fourth, dig deep and ask questions. Lastly, look up, become aware and watch your surroundings because you, like Shelia Fedrick, could rescue a trafficked person.