My Story

Two of my cousins sexually abused me while I was between the ages of seven and nine. Once during an assault, their father (my uncle) walked in, watched what was happening, quietly closed the door, and walked away. I have forgiven them all.

I believe recounting details of my abuse (whether to myself or to you, the reader) only serves two productive purposes. First, it demonstrates my personal connection to trauma, resilience, and survivorship. Survivors have a unique vision into the cultural narrative surrounding sexual violence, and any narrative without our explicit input is incomplete at best and patronizing at worst. Second, recounting these details provides comradery and empowerment to other survivors. The second point is important for several reasons.

Survivors often feel alone. Survivors often feel disempowered. Survivors often feel unheard and unbelieved.

For these reasons and more, many survivors, and I would argue most survivors, do not report their experience of violence. I am using this blog post to explain #WhyIDidntReport, and why others feel unable to as well.

You Never Go Back to Who You Were

I use the analogy of a watercolor painting to explain the sensation of a life disassembled, disjointed, and displaced from trauma. Imagine that you try to recall a particular scene from your life. The general forms are there, colored with vaguely familiar hues and shades, and you sense what the scene depicts as a whole. But you never get the sharp edges and the clearly demarcated lines. This is what it is like for me when I attempt to paint my childhood.

My watercolor painting has always been a glorious meeting of sun, sky, and sea – dark, deep, and turbulent waters underneath. My watercolor painting is the ocean under the setting sun.

In my experience, “a life disassembled, disjointed, and displaced” means losing time in two major ways: Losing memory and losing relationships. The question of memory, in particular, is an issue that plays out in courtrooms over and over again when allegations of sexual assault are leveled by a survivor. In my experience, it is entirely possible (and probable, given the trauma and humiliation inherent to any form of sexual violence) to recall with crystal clarity some details of your attack while at the time having no recollection of other details. Certain details will raise to the surface, such as the music that was playing in the earphones pressed against my ears, the glint of my cousin’s braces, the brown eyes of my uncle, the smell of biscuits in the oven, the taste of adrenaline. Others remain buried on the ocean floor.

The memory of the abuse came flooding back into my consciousness during my first year of college, and at that moment, I realized just how much of my life I had lost. I was walking home from a party with a close friend at the time, and I kept sensing an Old Enemy. I couldn’t quite tell what this Enemy was – as I kept walking, chatting with my friend, I felt tears in my eyes. I stopped walking and tears poured. I remember sitting down on the sidewalk with my friend, and very suddenly, with no prompting, admitting to my friend “I was sexually abused by my cousins”. This was the first time I ever shared my experience with another. To this day, I have no indication why the floodgates opened at that moment in particular.

Over the course of four and a half years, I worked painstakingly to make sense of my childhood, to reinsert control over my life and my choices, and to sublimate my experience to better empathize with and transform others with similar experience. I went to my alma mater’s counseling center, committed to integrating my trauma into my present self. I joined a student coalition advocating for sexual assault survivors, banding with other student survivors like myself. I interned at a nonprofit aiding survivors, finding my life’s calling in post-traumatic transformation.

Every Fall semester at my alma mater, both advocacy organizations I was involved with co-host a Shadow Event, where student survivors of sexual assault share publicly their stories to classmates, faculty, staff, and the local Newport News community. The survivors are blocked from public view by a veil; all the audience can perceive is the survivor’s silhouette on stage and her or his voice over the speakers. Survivors become storytellers, and in 2014, I became a storyteller. Each of us had the opportunity to air grievance, to speak truth to power, and (most importantly) to heal in our shared spirit of survivorship and transformation. I keep my testimony that I read the Shadow Event close. Sometimes I’ll read back through it, reliving the power of what it means to stand in front of an audience of my closest friends, coworkers, mentors, professors, and fellow survivors.

This power resides in our very core: It is the power from speaking our Truth to both an audience and, most importantly, to ourselves.

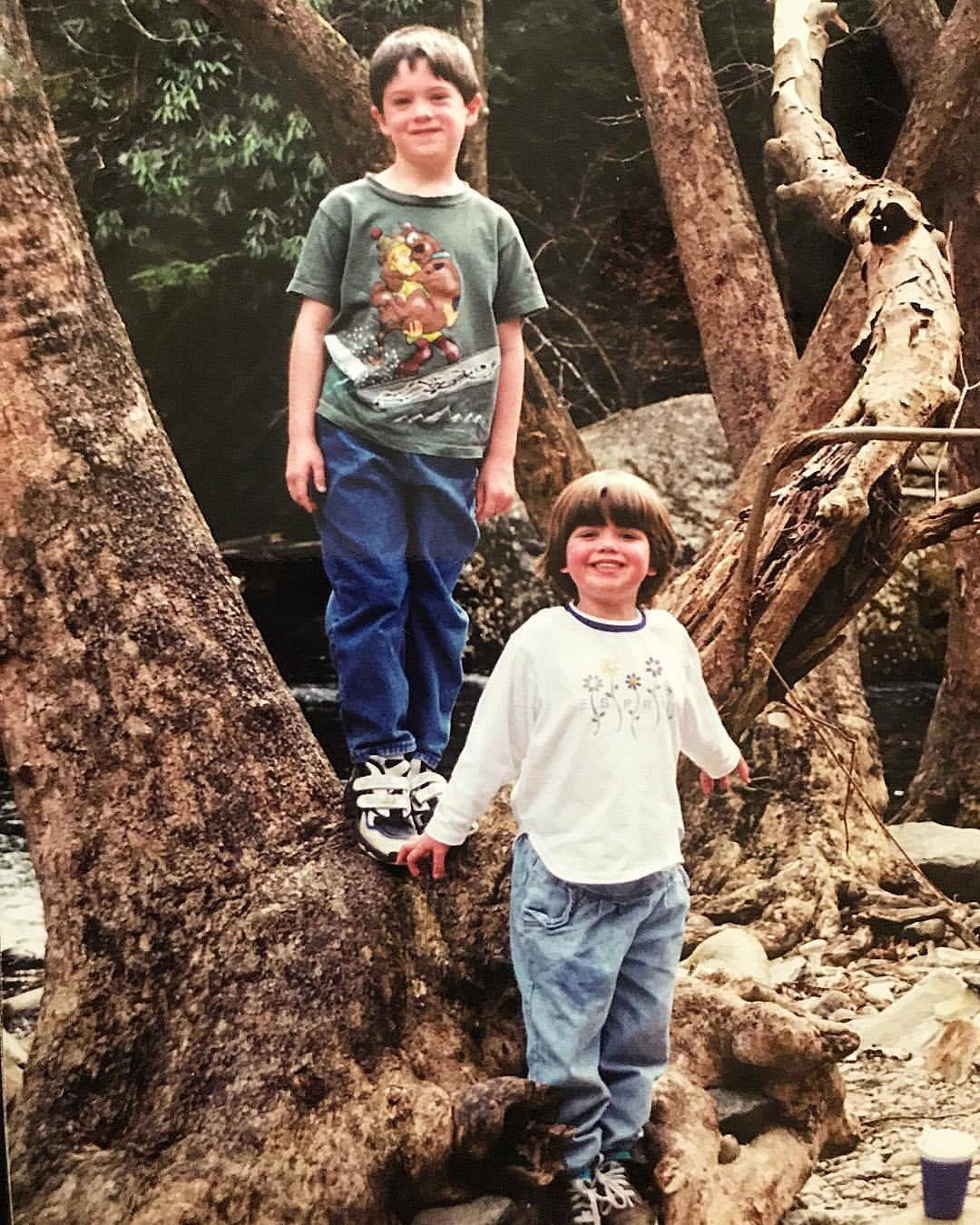

And even now, there is much work to be done, many relationships to repair. For several years after surviving the abuse, I obsessively held my Secret as close as possible, diving as deep inside myself as I could to avoid close personal connections. Many times, I seethed at the abject injustice of it all. I displaced my hurt on people I love, and there are indeed amends to be made for those dark moments. All the while, I could only remember flashes of childhood experiences: The t-ball team, playing with my sister in our neighborhood, voraciously reading Harry Potter, learning about oceanography in 4thgrade and knowing what it was like to have an ocean inside your mind. To this day, even after all the soul- and mind-work, the unifying thread of my childhood narrative is lost to me. I am fine with that. If I am certain of one thing, it is this:

When it comes to surviving trauma, you never go back to who you were.

#BelieveSurvivors

When an individual is traumatized at the hand of another, all meaning in the survivor’s world is shattered. You stop believing in many things – most notably, you stop believing in yourself, often repeating unholy mantras:

‘I asked for it.’

‘I could have stopped it, but I didn’t.’

And the worst, ‘I deserved it.’

Ideas of self-concept are twisted and reformed by dark imaginings, by fixations on memories of the traumatic event, and by questions such as ‘how could anyone do this to me?’ Many of us stop believing we are worth the discomfort felt by another when we tell them our story – we clutch our stories tight because we will, inevitably, end up on the receiving end of pitying looks and on the receiving end of heavy (and also very awkward) silences. The final tragic reality is that many survivors, especially women survivors, are simply not believed when they recount their abuse. When they share their testimony, they are met with suspicion and outright hostility.

Take, for example, the situation playing out between Ford and Kavanaugh. Last week, Dr. Christine B. Ford recounted her story of sexual assault at the hands of Supreme Court nominee, Brett Kavanaugh. Dr. Ford’s testimony and the tenacity of other survivors of sexual assault convinced enough members of the Judiciary Committee to commit to an FBI investigation regarding any potential incidents of sexual misconduct by Kavanaugh.

As both a survivor of sexual assault and as a human rights researcher committed to national and international standards related to due process, the Ford-Kavanaugh situation has been a nightmare. Many on the right believe Dr. Ford & her story serve solely as political pawns, used and abused by the Democratic Party. Many on the left believe Kavanaugh is a de facto rapist, aided and abetted by a Republican Party fully cognizant of Kavanaugh’s crimes. I cannot speak to what happened between Ford and Kavanaugh, so I will not indulge in speculation. Here’s what I can speak to:

99.4% rapists will never see a jail cell, 94.3% will never be arrested, and 69% will never have their violence reported to police.

Arguments have also been made that the men should fear being falsely accused of sexual violence (this says nothing of female perpetrators, such as one of my abusers). Intentional false allegations do indeed comprise 2 – 7% of cases brought to law enforcement. Compare that statistic with the others I listed prior.

It is very apparent to me, and to many other survivors as well, both the American judiciary and culture-at-large have failed their collective tasks of acknowledging, prosecuting, and preventing this form of violence. I also look to the vitriol Dr. Ford and her family are experiencing as evidence of these failures – failures completely visibly across the entire American political drama, irrespective of Kavanaugh’s guilt or innocence. I have wondered (for many years now, not just within the present circumstance) what structural barriers maintain this status quo, discouraging survivors from speaking out, inspiring savagery against survivors. Here are some of my theories:

- Cultural taboos against speaking openly about acts of sexual deviance pressure survivors to remain silent about their story.

- The perceived power status of the accused party intimidates survivors from sharing their stories.

- If believing a survivor means disrupting the conventional order, order usually prevails.

- These three factors (taboo, power, and order) have discrete mechanisms to suppress survivors and to shield the accused, including:

- Shaming the survivor (‘Khan couldn’t have raped her – did you see what she wore to the party?’)

- Questioning the credibility of the survivor (‘Anita Hill was working with interest groups bent on destroying Clarence Thomas’s chances to join the court.’),

- Normalizing sexual violence (‘So what if Trump said he grabs women’s genitals? That’s locker room talk.’),

- Minimizing consequences for perpetrators (‘Serving jail time is not justice for Brock Turner.’)

And from my joint perspective as a survivor and social scientist, here are the opportunities we all share in order to move forward the national conversation about sexual violence:

- Normalize conversations about sexual behavior, starting within the family.

- If you find yourself questioning the credibility of any survivor, ask yourself why.

- Empower survivors to speak for themselves, not for others to speak on their behalf.

- Mandate consent laws and sex education are taught in public schools nationwide.

- Publicize who are mandatory reporters and local / state / national / international mental health services (now that I am teaching, I put this information front and center in my syllabus).

- Familiarize yourself with verifiable statistics of sexual violence – it is much more common than any of us would like to believe.

For fellow survivors reading this post, know that there are many mental health services you can utilize (for other guy survivors like me, visit 1in6 and consider reading my friend’s story about why he didn’t report). As the Ford-Kavanaugh story gains more traction, many of us will be threatened by feelings of being re-traumatized. Here’s one website that can help (a special thank you to my colleague in UAB Public Health for her empathy and for this resource!). Dr. Ford’s testimony is a reminder for us to always show courage, to speak truth to power, and to wear your mantle of survivorship with pride. Know that you are never alone. And know that I believe you.

I’ll leave you all with the words of Dr. Judith Herman, psychiatrist and author of Trauma and Recovery:

“Those who stand with the victim will inevitably have to face the perpetrator’s unmasked fury. For many of us, there can be no greater honor.”