The Human Rights Watch collected evidence in between January and June 2020 that closely reviewed the trial cases of 75 alleged child offenders who were recruited by the Islamic State (ISIS). The cases had led to the misconstrued holding of the children, but upon review, the Human Rights Watch ordered the release of the children, using reasons like a lack of evidence and preventing double jeopardy, as well as provisions of Iraq’s amnesty law. The 2016 Iraq Amnesty Law offers amnesty to persons who can show that they joined ISIS or another terrorist group against their will and did not commit a serious offense prior to joining the group.For years, Iraqi and Kurdistan judicial authorities have charged hundreds of children with terrorism for alleged ISIS affiliation. Several of the charges have been based on the dubious accusations and forced confessions of these children, regardless of the extent of their involvement with ISIS, if any. Such behavior from authorities has led to an international norm that children recruited by armed groups should be treated as victims, first and foremost, not as criminals.

In January 2020, a committee formed under the Nineveh Federal Court of Appeal and Bar Association, consisting of a judge, a general prosecutor, and a social worker. This committee adjudicated the cases of suspects who were children at the time of their alleged alliance with ISIS. The approach taken by this committee was one of compassion and complied very well with acknowledging the human rights of these child suspects. In June 2020, Iraqi judicial authorities dissolved the committee, saying it had reviewed all the pending cases, but another committee in Nineveh, Iraq, continued adjudicating such cases. In August 2020, an anonymous source close to the Nineveh Bar Association told the Human Rights Watch that the committee had reviewed 300 case files before being disbanded in June. They convicted 202 people, dropped charges against and released 31, and pardoned and released 44 under Iraq’s 2016 Amnesty Law. Three cases were dropped because the defendant had already served a sentence for the same crime, so to not invoke double jeopardy, the committee permanently ceased proceedings against the three people.

The committee, unlike other Iraqi courts, attempted to review individual cases more fairly and better apply international standards. By doing so, it was able to convict the guilty and release the innocent, which Iraqi courts do not have the best record for. In the Iraqi-Kurdistan regions, children have been tried in Kurdistan and re-tried for the same crime in Baghdad-controlled territory, with courts ignoring whether or not the child had been acquitted or convicted and already served a sentence in Kurdistan.

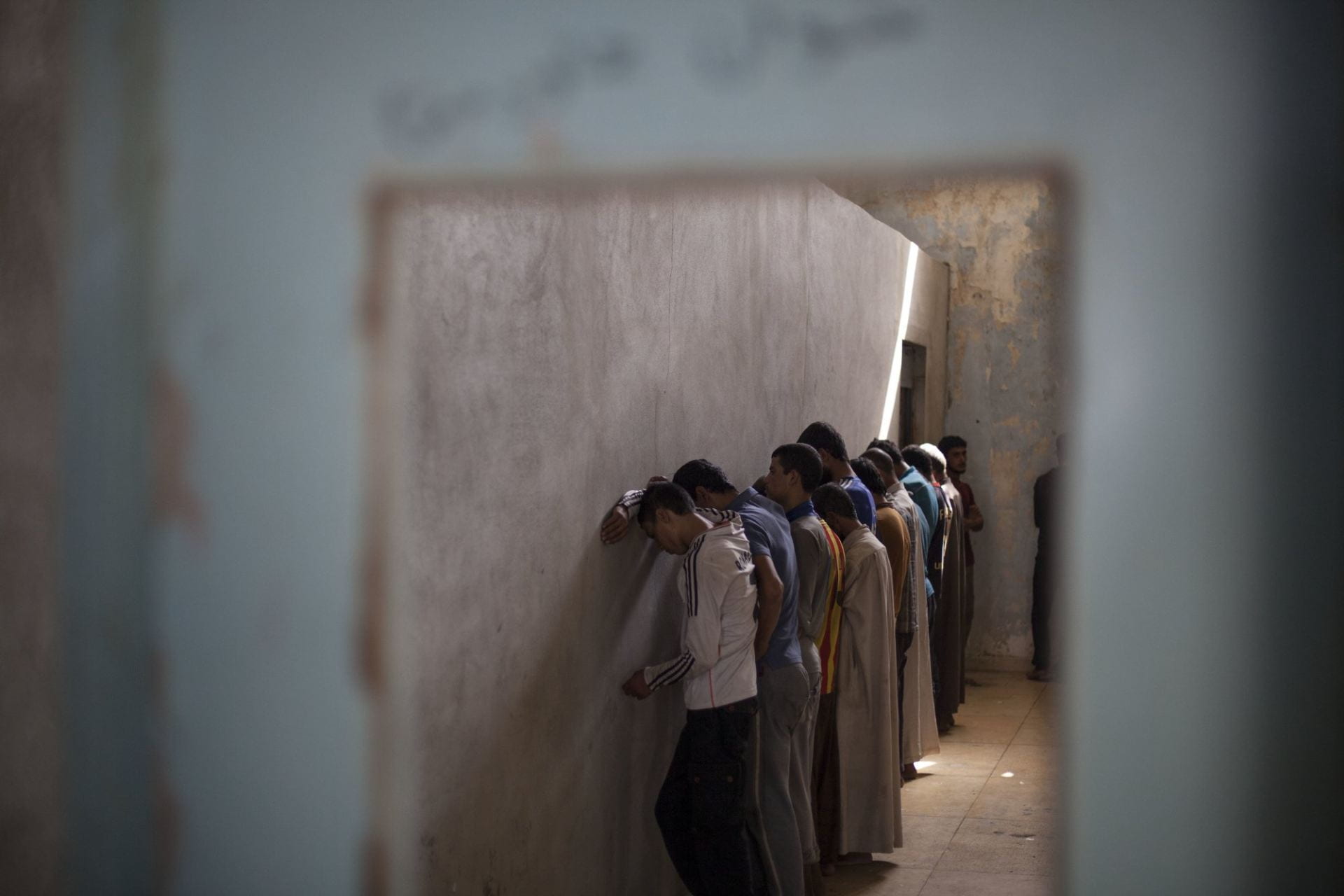

This has been the case since the advent of ISIS in Iraq: hundreds of children have been charged with crimes of terror, and such convictions have been justified under Iraq’s 1983 Juvenile Welfare Act. The Act states that the minimum age of criminal responsibility is 9 in Iraq and 11 in the Kurdistan region. Children that are under 18 at the time of the alleged crime are sent to a “youth rehabilitation school” which is designed to provide social rehabilitation and reintegration via educational or vocational training. However, a source within the Tal Kayf prison said that “the cells are identical to those for adult detainees, with no access to any reading or studying materials besides the Quran.”

What needs to be done?

The Nineveh committee is the first step towards attaining a more efficient and fair judicial system in Iraq where ISIS affiliation does not automatically translate to imprisonment. Children should only be detained as a last resort and for the shortest appropriate period, in compliance with international law. Countries should provide proper assistance for children illegally recruited by armed groups and/or forces, including assistance for their physical and psychological recovery and social reintegration. The Iraqi government and Kurdistan Regional government should amend their counterterrorism laws to end the detention and prosecution of children solely for participating in ISIS training or membership with recognition of international law that prohibits recruiting children into armed groups. And the High Judicial Council should permit committees to delve into more counterterrorism cases to avoid the trend of double jeopardy, while instructing judges across Iraq to release all children who have not committed crimes and ensure their proper rehabilitation and reintegration.

In the first half of 2020, Iraq has taken an essential step towards protecting the rights of children rather than trampling them. But this progress is at risk of Iraqi officials do not implement such steps elsewhere.