How exciting to have been invited by Dr. Lisa McCormick to accompany her PUH 496/696 Exploring Population Health course to Panama! Travelling with a group of UAB students to Panama has really been thrilling. Before we left Birmingham, the students spent a few days preparing themselves to get the most out of this experience by learning about public health programs in Birmingham, Alabama and the historical connections between Alabama and Panama. During that time, I have been doing my own research so that I will be prepared. Did you know that the population of Panama is 4.1 million and the population of Alabama is 4.9 million? And, Panama City with a population of 1.8 million is the largest city in the country much like Birmingham is the largest city in Alabama with a population of 1.15 million. I wonder what other things we will find in Panama that are similar to Alabama.

I have been practicing my Spanish to prepare myself.

Wait, I think I see Panama!

Our first day in the country and already we are on the go. We went to the Ciudad de Saber. That is the ‘City of Knowledge’ in English. Our first stop was at the Interpretive Center. There we learned about the history of the relationship between United States and Panama. Being on what used to be a military installation that is now being used to facilitate collaborations between non-governmental organizations, schools, universities, and tech companies is so encouraging. There is a feeling of openness and partnership as all of the resident-organizations have committed to engaging the Latin American communities to improve the health and well being in the region.

It reminds me a bit of the Innovation Depot in Birmingham, which has become the epicenter for technology, startups and entrepreneurs. It has truly become the hub of economic development in Central Alabama.

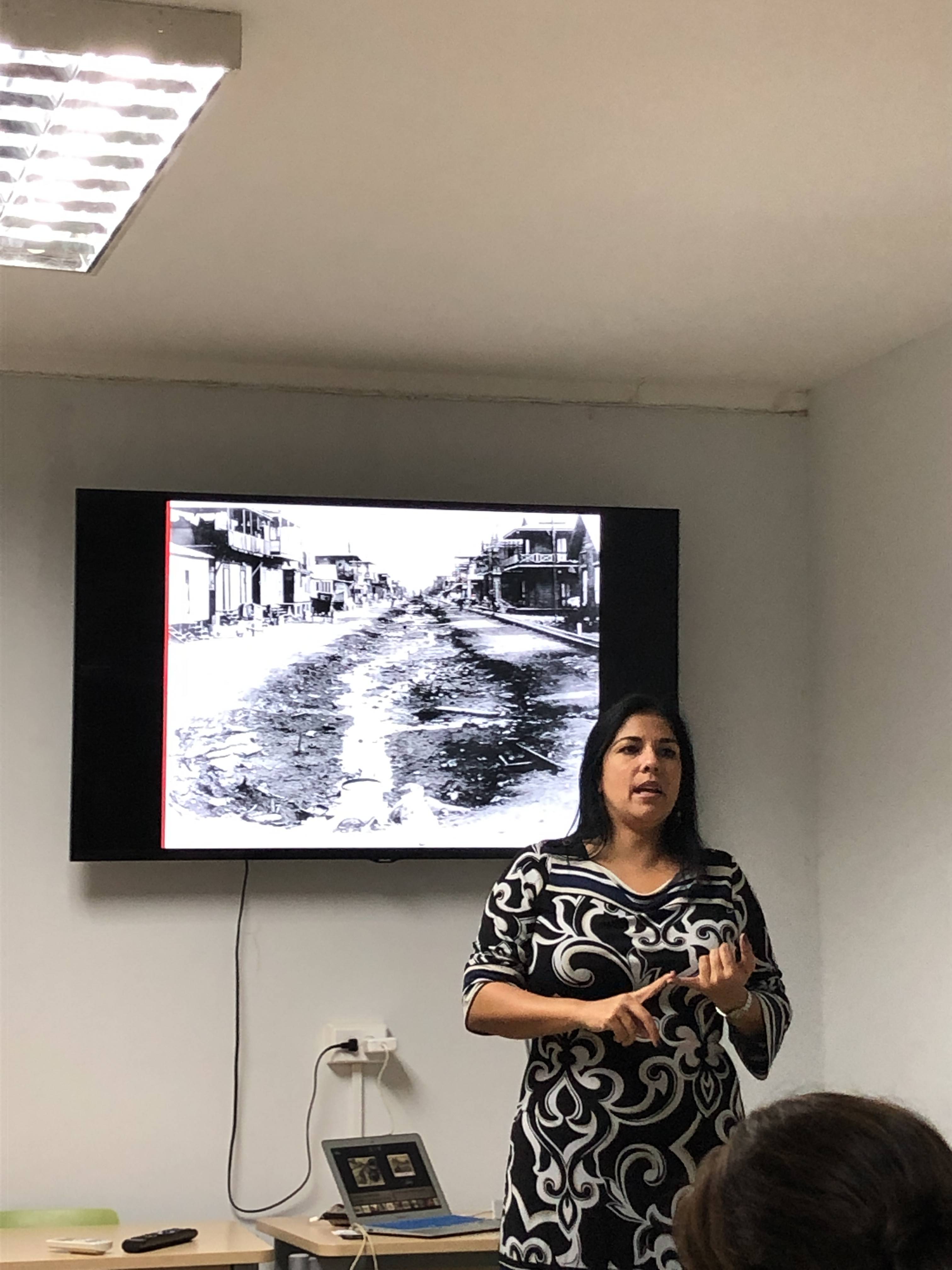

Then after a great lunch, we went to the University of South Florida Health office to hear Dr. Arlene Calvo speak about historical aspects of health research and the public health system in Panama. I felt very pleased to hear about how Dr. William Gorgas from Mobile, Alabama was responsible for reducing the transmission of yellow fever and malaria in 1904 by creating the necessary infrastructure. His efforts facilitated the completion of the Panama Canal.

Did you know that the Gorgas Course in Tropical Medicine was launched as a collaborative partnership between the UAB School of Medicine and the Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia with the purpose of filling an educational gap for the international medical community seeking an intensive experience in tropical medicine with a focus in clinical activities and substantial exposure to real patients. After more than two decades of uninterrupted activity, the Gorgas Courses have trained more than 800 participants. Currently, the Gorgas Courses in Clinical Tropical Medicine are held at the Alexander von Humboldt Tropical Medicine Institute in Lima, Peru. The diverse geography of Peru provides participants with an unparalleled opportunity of a first-hand exposure to the unique wide spectrum of tropical diseases that concentrate in this facility including: anthrax, cholera, leptospirosis, leprosy, HTLV-1, HIV, viral hepatitis, yellow fever, rabies, malaria, leishmaniasis, Chagas’ disease, strongyloidiasis, and histoplasmosis.

On the first Friday of our trip, we visited the Las Mañanitas Health Clinic. Las mañanitas is the traditional birthday song sung in Latin American countries. Las Mañanitas Health Clinic is funded by the Panamanian Ministry of Health and host a multitude of preventative services. It serves a community of over 60,000 residents! The staff here is committed to providing services to any and all who need their care at no or very minimal costs.

It is also interesting to note, that much like the environmentalists that let us shadow them in their house-to house visits in Las Mañanitas who are preparing to battle mosquitos and subsequently the diseases that they spread during the rainy season, the City of Birmingham Mosquito Spraying began spraying Birmingham neighborhoods on Monday, May 6. This coincides with the summer increase in mosquitos that need to be controlled to reduce the risks of diseases such as Zika and West Nile Virus in our communities. The Birmingham technicians treat each neighborhood weekly on the scheduled day of the week, weather permitting. However, unlike what we saw in Panama, residents in Birmingham can request an exemption and have their address listed as a “no spray” address.

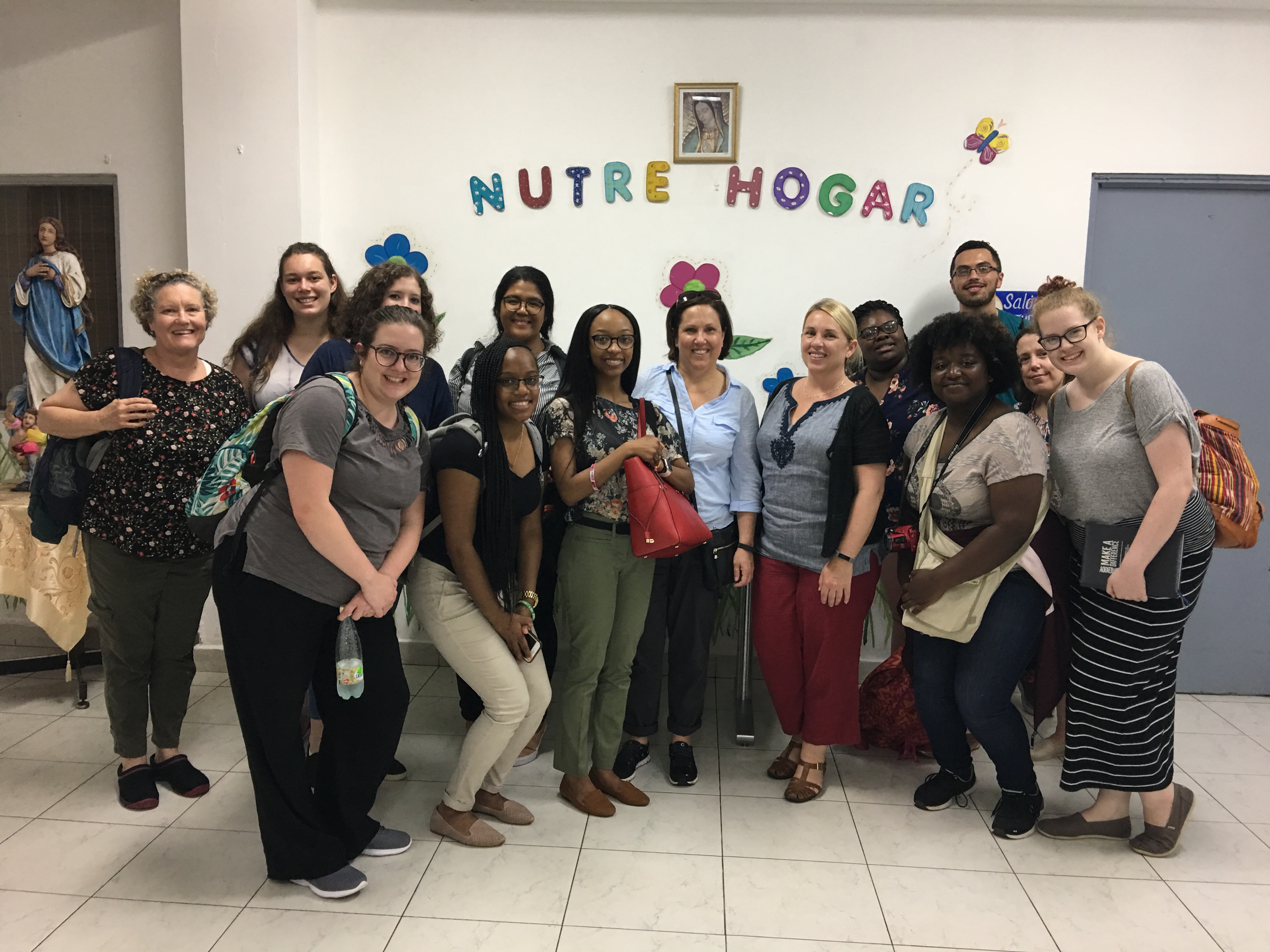

Next we visited the non-profit, Nutre Hogar. It was located not far from the Panama Canal and is a home for indigenous children suffering from malnutrition. Cada Dia Mejor means “every day better” in English. This Panamanian non-profit is committed to treating the nutritional needs of children a day at a time at their facility. It was interesting to see young children temporarily residing in a medical unit/home for nutritional therapy. In Alabama, we have programs like the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) that provides federal grants to states for supplemental foods, health care referrals, and nutrition education for low-income pregnant, breastfeeding, and non-breastfeeding postpartum women, and to infants and children up to age five who are found to be at nutritional risk.

When touring Casco Antiguo, the colonial town of Panama City, we viewed a number of beautiful churches. Much like in Alabama, religion plays a significant role on culture in Panama. This was a good time for us to reflect on how religion impacts the public’s health through policy and educational accessibility.

During our time in Panama, we spent a lot of time on buses getting to all of the educational places that we needed to go. I have noticed billboards along almost every roadway that feature famous international figures in a public health campaign to encourage seat belt use and adherence to the speed limits. But feeling like there were so many near misses while riding in the buses and watching pedestrians cross four lanes of traffic on the highway, I was curious about mortality rate associated with traffic accidents. I just had to check. What I found is that according to the latest WHO data published in 2017, Road Traffic Accidents Deaths in Panama reached 420 or 2.44% of total deaths. In Alabama in 2017, according to the Alabama Department of Transportation, there were 857 fatal crashes leading to 948 fatalities. Public health education and promotion regarding traffic safety are necessary everywhere. Wait a second while I put on my seatbelt.

While we were in Chitre’ we participated in three service learning activities, two at elementary schools and one at a senior center. The elements that make service learning effective are providing what the community asks for using course content to enhance experiential learning for mutual benefit, being flexible and adaptable, and reflecting on the experience by answering: what was done?, why did it matter?, and now what will be different? The UAB students offered health education to Panamanian schoolchildren and a group of seniors based on the requests of schools in Chitre’ to reinforce important public health concepts. Before arriving in Panama, the UAB students worked to prepare appropriate lessons, however, once arriving in each location, they had to adapt the plan to work in the situation. This was amazing to watch. Our students used their soft skills to be able to effectively change the initial plans to appropriately fit each situation. Debriefs following each service learning experience, daily reflections and this blog are the many opportunities that were used to reflect on the personal learning.

The service learning days were perhaps my favorites because I watched cultural and language barriers fall while the UAB students sang, laughed, and played games with the school children and danced and danced with the women.

Much like the state of Alabama, Panama has a large urban area at the center of its boundaries. Birmingham and Panama City both sit squarely at the center geographically. Santo Tomas Hospital and UAB Hospital both provide the best medical available in their regions. Yet, both have large rural areas that are remote from accessing this due to distance or lack of available transportation. The public health systems provide preventative care through the Ministry of Health regional clinics in Panama and the county public health departments in the United States. There are smaller hospitals that provide services to these rural communities, but in an extreme health event patients need to be brought to Panama City and UAB hospitals.

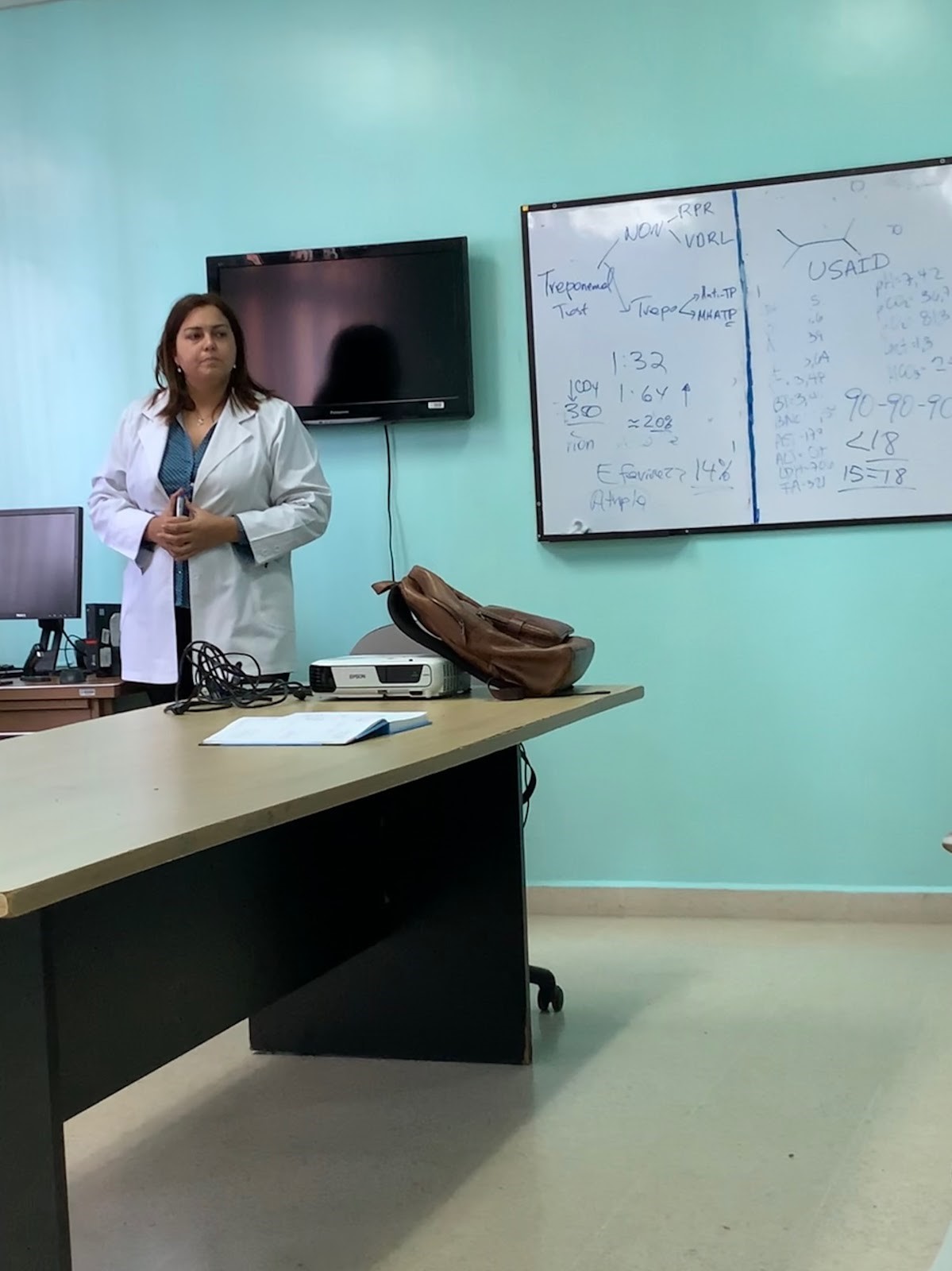

This urban vs. rural access to care was very evident when we spoke with Dr. Anna Arrouz. She spoke about how HIV-positive patients in Panama often need to come to Santo Tomas or the Social Security hospital in Panama City to receive testing, access anti-retroviral therapy, or receive hospital care if they are undiagnosed and contract a life-threatening co-infection and must be hospitalized with AIDS. I am reminded of the revolutionary work of Dr. Michael Saag at UAB back in the 1980s when he and his UAB co-investigators traced the source of HIV, helped develop revolutionary treatments, and brought hope to patients from Alabama and the world. Dr. Arrouz with her limited resources is bringing hope to HIV patients in Panama. Her commitment to both the prevention and treatment of HIV is making a difference.

When we went to the Biomuseo, the biodiversity museum, I was struck by the natural marvels that compose all of Panama’s ecosystems and I was thrilled by their commitment to preserving that diversity.

Likewise, maps published in 2017 by biodiversitymapping.org and based on maps developed by Clinton Jenkins at the Instituto de Pesqusas Ecologicas published at proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences have revealed that Alabama is one of the most biodiverse states in the areas of aquatic species and trees. Many environmental nonprofits (the RiverKeepers and Nature Conservancy) in Alabama have realized the importance of that distinction and work diligently to preserve that diversity.

On the day that we went to see the Embera’, one of the many indigenous groups in Panama, I thought of the indigenous groups from our home state.

Did you know the name “Alabama” is a Muskogeannative American word? It meant “campsite” or “clearing,” and became used as a name for one of the major tribes in the area, the Alabama (or Alabamee) Indians. The original inhabitants of the area that is now Alabama included the following tribes: Alabama, Biloxi, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Koasati, Mobile, and Muskogee Creek.

Now it is time to say good-bye to Panama. It was an amazing trip full of meaningful connections, deep experiences, cultural exchange, and service learning. I learned so much about population health, health equity, and social determinants of health during the last 11 days. Travelling and working with Dr. Lisa McCormick, Dr. Ela Austin, Meena Nabavi, and the thirteen public health students was both interesting and fun. I am a bit tired, but I am going to use the time on the flights back to Birmingham to reflect on all that we have experienced and learned.

I hope to return to Panama with other UAB students. I can see how so many of them will benefit from the experience of learning in a country that has one of the fastest growing economies in the world, a public health system committed to the wellbeing of its citizens, and innovative efforts around environmental sustainability.

And between you and me, I certainly hope that I will be invited to join the Population Health course again next year. I hear that they are going to England!