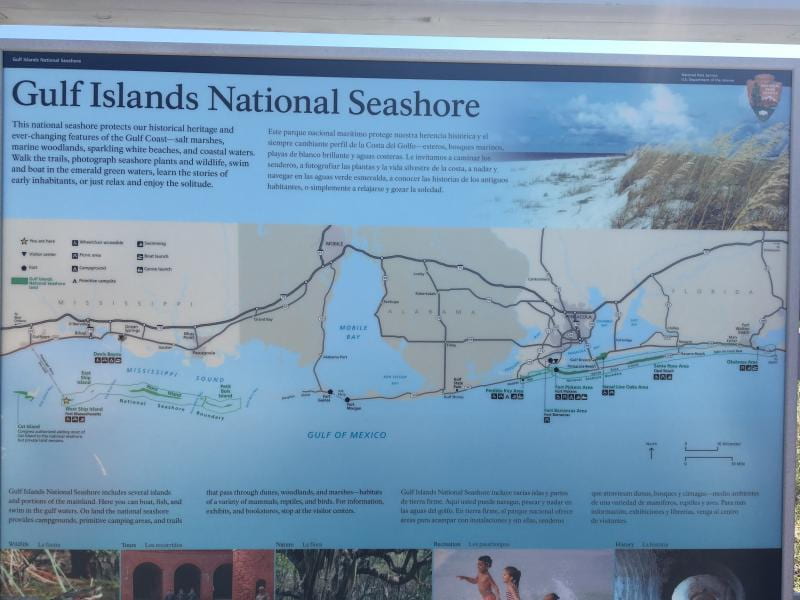

During this visit, we learned about the Alabama Department of Health’s (ADPH) Southwestern Health District. This district includes the following counties: Baldwin, Choctaw, Clarke, Conecuh, Dallas, Escambia, Marengo, Monroe, Washington, and Wilcox (see the image below for a graphic representation). It may seem odd to you that Mobile county is not included in this district, as it is so geographically close. However, both Mobile and Jefferson counties operate somewhat independent health departments and as such, have become their own districts.

The Southwestern District is largely rural with median household incomes per county ranging from ~51K (Baldwin) to ~24K (Wilcox). The percentage of folks who live in poverty ranges from 11.7% (Baldwin) to 35.4% (Dallas). Baldwin has a higher socio-economic status than the other counties due to its lower half being a great destination for tourists and people who want to live by the beach. Dallas and Wilcox Counties are primarily African-American (70%). Naturally, we wondered how the Southwestern District Administrator addressed the diversity between counties with regard to income, poverty, race, and other social determinants of health.

Luckily, we had the opportunity to sit down with the District Administrator, Chad Kent, the Assistant District Administrator, Suzanne Terrell, and the Director of Field Services for ADPH, Ricky Elliott. We met them at the Escambia County Health Department and learned about the many programs and services offered at each of the local health departments, like the one we were in, throughout the District. These programs included, but were not limited to family planning, sexual health screening (STI and HIV testing), lead screening, home health programs, cancer detection programs, and diabetes education. Some counties even offered additional maternity services and included peer breast-feeding educators. We were also surprised and grateful to hear that in one county, the social worker actually brought birth control to a client who had no transportation. While this was likely an unlikely occurrence, the compassion of the local health department staff for their communities and their willingness to go above and beyond the call of duty does not go unrecognized.

The commitment of the staff of the Escambia County Health Department and the Southwest District to their residents is impressive, especially with their dedication to make healthcare accessible to all that live here. While we were discussing this with them they shared with us a story of an elderly couple who would have had to drive over three hours one way to see a nephrologist at UAB. The trip was difficult for the couple; navigating Birmingham’s traffic and parking was a source of great stress. Through ADPH’s Telehealth Program, this couple and others can now “meet” their doctor at their local public health department. Doctors can communicate with patients via a video call during routine follow-ups. Some conditions can even be diagnosed and treatments recommended via this technology. This program is breaking down transportation as a barrier to accessing the care their residents need in order to live healthy and active lives.

While Telehealth is certainly a technological achievement, the District leadership was also very excited about two new changes coming to the District (and the state). First, a new electronic health record (EHR) system will be implemented later this year. An EHR system will allow for greater continuity of care within the ADPH system, as well as increase the ability to communicate with other providers. Second, Women, Infants and Children (WIC) is going somewhat digital as well. Traditionally, WIC clients have received vouchers that they can turn in for certain goods at their local retailers. Soon, WIC clients will receive a WIC card that will be loaded with a certain amount of money to purchase WIC items. This eWIC program enables clients more flexibility in the WIC items they can receive, saves time, and reduces any voucher and low income related stigma. Additionally, data from purchases will be used to inform other WIC services moving forward. Overall, technological advances have really increased the ability of ADPH to learn from their communities and adapt to better meet their needs.

Team 2 – Tessa, Kachina, and Dekennon