Approaching matters from a public health viewpoint often relies on the perspective of an outsider looking in. In our own environment, it is difficult to see the nuances and minor differences which exist across various communities. Looking at it another way, when we are part of the forest, we often do not realize the slight differences amongst the trees. It would be easy to believe that visiting another English-speaking country would be more of the same, but as you will soon find out, that is definitely not true!

The classroom today consisted of two distinctly different organizations, however, as we quickly found out, much of their approach to public health issues is quite similar. Stop one was the Terrence Higgins Trust.

Walking into the Terrence Higgins Trust (THT), the UK’s oldest HIV and Sexual Health charity, we were greeted by a vibrant atmosphere and a chipper staff. Southern-style hospitality was extended with a wide array of snacks and beverages served. Of course, instead of our beloved Alabama staple of sweet tea, we were offered a variety of English-style hot teas and “biscuits,” or cookies as we know them.

Friends and family of Terrence Higgins, often referred to as “Terry,” originally established this now national trust after he passed away due to AIDS-related health complications. Forty years later, the trust still stands and has grown to serve communities across the UK. Specializing in HIV and Sexual health, THT works with the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) and other charities, with a goal of bringing increased equitable access to sexual health care across all races, genders, sexual identities, and geographic locations.

Students learned about one of the UK’s primary health goals for HIV, the 95-95-95 target by 2030; meaning, that 95% of those living with HIV are diagnosed, 95% of those with a diagnosis are receiving treatment, and 95% of individuals in treatment have an undetectable viral load. In 2022, the UK is certainly on track to meet this target with current reported levels showing 95% diagnosed, 99% in treatment, and 97% with an undetectable viral load; however, the numbers don’t tell the whole story.

Stigma and fear still dominate much of the space around sexual health. In the US and UK, stigma against sexual health remains pervasive. Healthy forms of prevention are often seen as promiscuous behaviors, causing many to fear visiting the UK’s sexual health services, which are provided by the NHS. Focusing on advocacy and fighting stigma, the THT brings a voice to those too scared to speak for themselves.

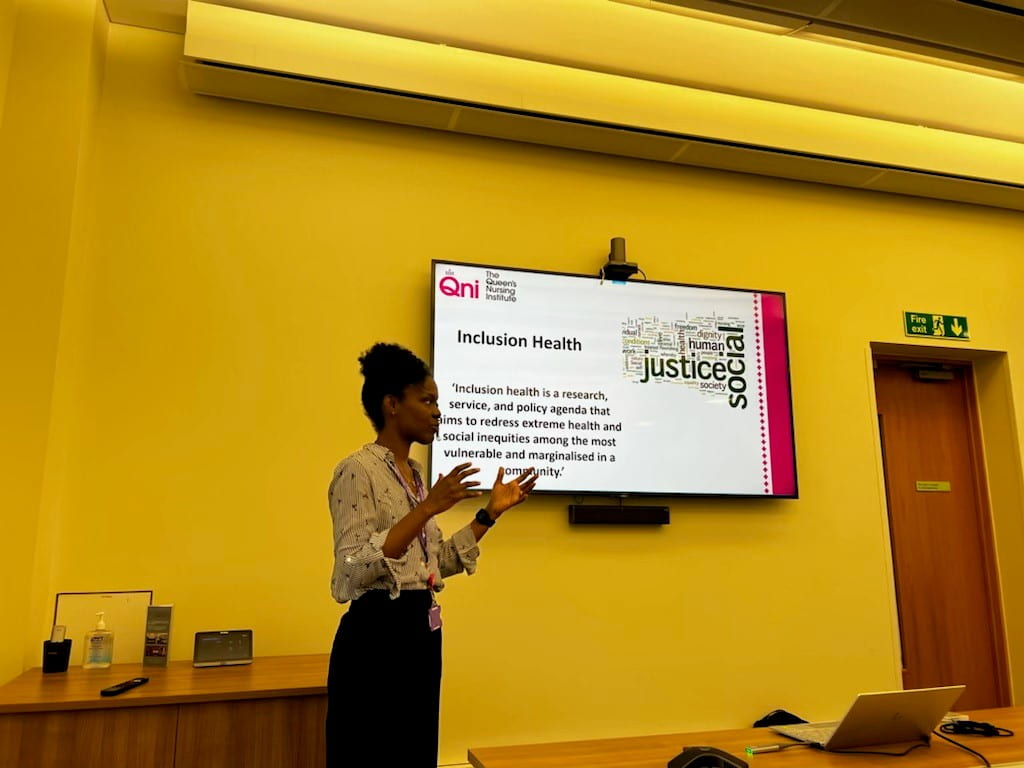

Much like communities in the US, progress most often begins in more urban environments. Most of the progress in HIV prevention and treatment in the UK is taking place within London’s 32 boroughs, leaving many surrounding less dense areas with little or no options for local healthcare. THT Research and Policy Officer Ngozi Kalu described this phenomenon as a “postcode lottery.”

The geographical disparity between cities and towns is brought to light as many in the HIV-positive community have suffered negative experiences meeting with their general practice (GP) doctor. In more rural areas, like Cornwall, some even described the experience of being told there is no HIV in their community, while actively seeking treatment for themselves.

For many across the UK, such stigmatized interactions are at the forefront of their experience, pushing many away from seeking treatment. This disparity is seen further in members outside of the LGBTQIA+ community, as many others who may be HIV positive do not know their options or how to access this specific type of care.

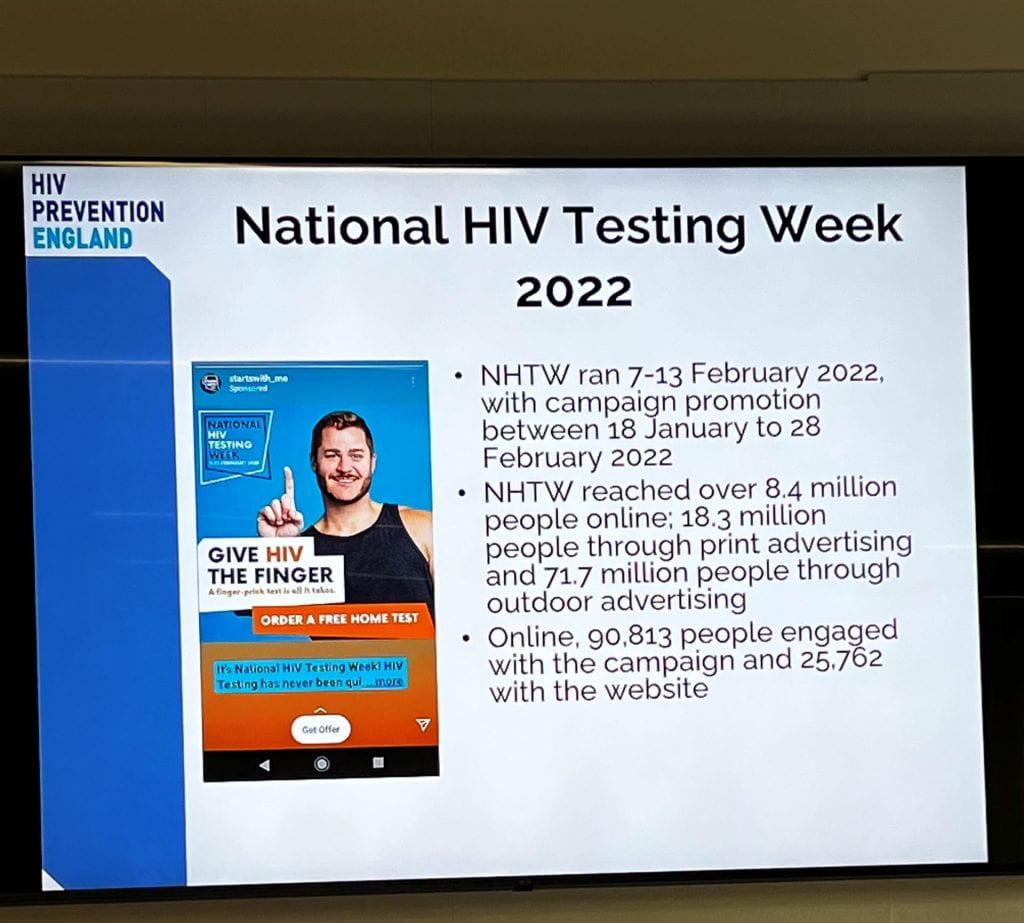

THT Prevention Program Officer, Alex Sparrowhawk, asked us what to do “when equity fails.” Unfortunately, there is no simple answer, magic beans, or silver bullet to save the day. The main goals of the THT are to work towards increased equitable access to sexual health services through expanding health care access in local pharmacies, starting a National HIV Testing Week, and establishing a policy to help implement age-appropriate sex and relationship education in schools.

If you’re interested in learning more about the work being done in the UK by the THT, follow the link to help Pubic Health Give HIV the Finger.

After our time at THT, we meet UAB MPH alumnus, Stacie June Shelton, MPH on the steps of St. Paul Cathedral. Stacie is Global Head of Education & Advocacy, Dove Self-Esteem Project at Unilever. Then group enjoyed a delicious lunch with Stacie at Samuel Pepys before heading to Unilever’s London headquarters. (As expected, this dining establishment served an amazing fish and chips lunch entree, which is a staple of the British dining experience.)

As is often the case in the U.S., the Unilever headquarters is also highly focused on security issues. All UAB guests were checked in through security and provided bright green stickers designating our status. Photography within the building was strictly prohibited.

The group gathered in one of Unilever’s many impressive and modern meeting rooms to discuss and learn more about Dove’s Self Esteem Project, which is a global outreach effort. Through this project, Unilever has data showing how this project, in partnership with UNICEF, has positively impacted multiple countries and helped young children in Brazil, Indonesia, and India with their self-esteem and overall body confidence. Although there are many different initiatives for those aged seven to 24, the main project group is young children from age 11 to 14. Looking back on some of our formative years during the same time frame, many discussed how impactful it would have been to witness media that acknowledges and promotes varied outlooks on inner and diverse beauty.

A positive relationship between self-esteem and body image begins with value in diverse beauty ideals. In order to achieve this, it is important to arm the next generation with tools to disarm toxic beauty standards. Dramatic change in standards, ideals, marketing, and thought processes must take place. Changing laws, media practices, and policies/practices of both government and non-government entities is necessary. One positive example of such change is the Crown Coalition which opposes discrimination against natural hair. [https://www.dove.com/us/en/stories/campaigns/the-crown-act.html].

Dove has a long-standing mission “to make beauty accessible to all women,” however, not all are aware of their important work in making traditional beauty ideals more inclusive and realistic. It was extremely impressive and impactful to hear about the amazing initiatives of Unilever from a UAB alumnus.

Shelton graduated from UAB with an MPH degree in health behavior. She worked for the Oregon State Department of Health and advocated for adolescent school health. She then turned her focus to International health, serving in countries including Kenya, Nigeria, and Sri Lanka. Currently, she is living just outside of London and enjoys the work she does as part of the marketing and communication teams on Dove’s Self Esteem Project. She shared that she is often the only public health specialist on projects, so is able to provide a unique and valuable perspective to the team. Stacie’s work is supported by Unilever and is part of their strategic goals, but a big part of her job is to serve as an advocate for her projects within the company and answer decision-makers’ questions such as “What, why, and how? What are the issues and their effects? Why should we push this initiative? How do we effectively get it across to the most vulnerable?”

With her impressive accomplishments and wealth of knowledge, it was a true privilege for the group to spend time with her. Her beliefs, ideals, and background were relatable and provided important insight into public health opportunities within corporations. Stacie June showed us what a career in public health could become.

Class time concluded with a glass elevator trip to the top of the Unilever building, where we experienced their newly constructed rooftop garden. From this spot, we were able to peer across the River Thames, one direction towards the Tower Bridge and London Tower, we were able to truly feel the beauty of London life and realize that our career dreams could become a reality.

And finally, we would like to share a more moving initiative of Unilever. The inner child of us all shed a tear from the emotional hook of the Dove Self Esteem Project: Detoxing Your Feed Campaign. [https://www.dove.com/us/en/stories/campaigns/detoxify.html]

One of the goals of this campaign is to promote media literacy and tackle the issue of why social media can have a negative influence on self-esteem.

We ask you, the reader, to share in our experience and consider how social media may impact your personal health. As a short experiential exercise, we ask you to take note of the first five to ten posts that show up on your social media feed. Ask yourselves these questions:

● How does this content make you feel?

● How often do you compare yourself to the people that you see online?

● Do you feel the need to change yourself in order to fit into a standard?

On a final note, we suggest you tune into the Appearance Matters Podcast! This captivating audio is the official podcast of the Centre of Appearance Research and is available on Apple, Spotify, and Audible.

Cheers!