“How did this happen?” “Is this America?” These are the contemplative and persistent questions that come to mind while walking through the Katrina Exhibit at The Louisiana State Museum. The exhibit is housed at The Presbytère, an eighteenth-century architectural gem on Jackson Square in New Orleans. It has been nearly thirteen years since Hurricane Katrina hit the city of New Orleans, but time stands still as we walk through the exhibit. The exhibit opened in 2010 and features eyewitness accounts, historical artifacts, interactive exhibits, and historical as well as scientific information on hurricanes, geography, and the levee systems. The museum was created to provide an educational experience highlighting the failed processes that led to the magnitude of the disaster and emphasizes the efforts toward recovery. The museum inspires its visitors to think about the importance of mitigation, preparedness, and response operations and the relationship between poverty and disaster outcomes.

The Katrina Exhibit was designed to answer questions posed at the beginning of our blog. From a public health perspective, it is important to evaluate the effects of hurricanes and how they impact the health and livelihood of a community. To quote the philosopher, George Santayana, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” The exhibit describes the history of larger hurricanes that have impacted Louisiana. After learning of Hurricane Betsy, a.k.a Billion Dollar Betsy, our group recognized post-disaster outcomes (e.g. disease, injury, death) and how these outcomes can be exacerbated by poverty and not having effective emergency protocols and mitigation systems in place. The exhibit showcases photographs and personal stories of the destruction which can be prevented in future storms.

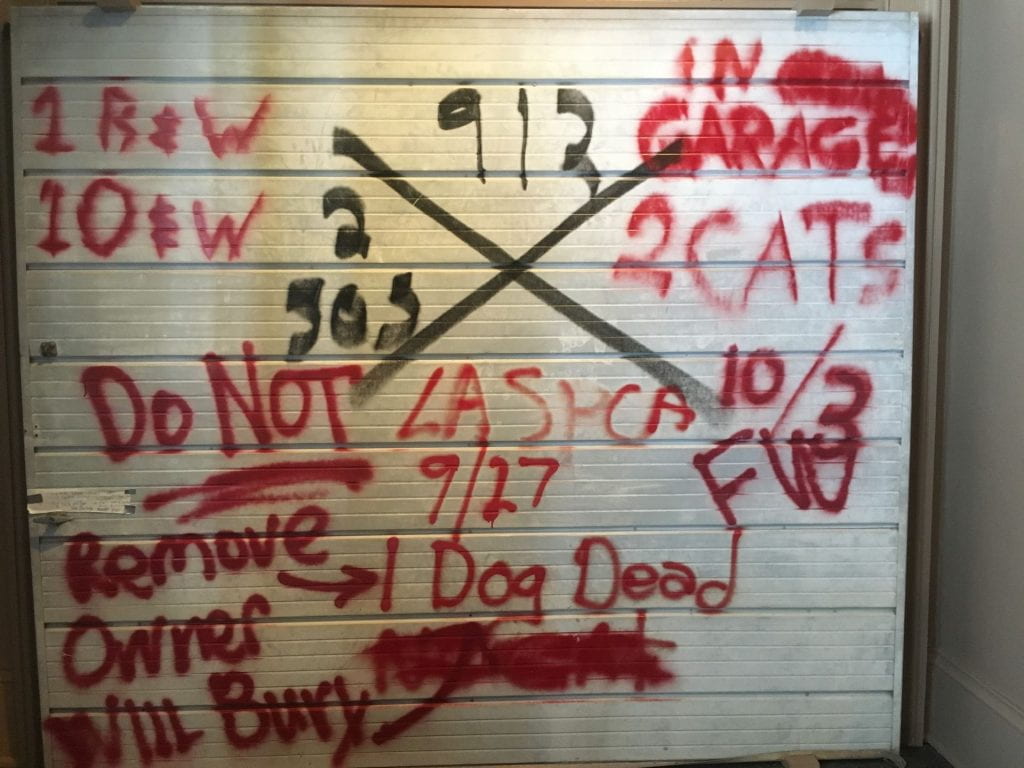

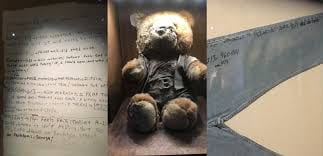

Katrina was not a discriminatory storm and affected all in her path. The aftermath of the storm left immense environmental impacts. As public health students, we recognized the social determinants of health while reading through the displays. There are too many facts presented in the exhibit to mention in this blog, but there were a few memorable stories that stood out. Seats from the Superdome were displayed to represent the shelter that was used at its height for 35,000 people. The living conditions within the Superdome were unfathomable with stifling temperatures, filthy conditions, and a disgusting stench. Another display features the diary of a gentleman, the late Tommie Mabry, who wrote about the conditions he experienced while stranded at his home. His memories are somber to read with his thoughts on survival, his thankfulness for friends and neighbors, and how he kept busy during the period following Katrina. Furthermore, Mr. Mabry wrote about being unwell and his worries about not having access to healthcare. Both of these displays from the exhibit are demonstrative of how the residents of New Orleans suffered.

“The Hurricane was fair, we were all affected, all devastated. The aftermath was not, the resources were not, the breaches were not. It was an injustice.”

Over a span of thirteen years, many efforts have been dedicated to social, economic, environmental, and infrastructure recovery in New Orleans. The former mayor, Mitch Landrieu, declared in 2017 that New Orleans is “no longer a recovering city, but a city that has recovered and is now moving forward.” Some community members beg to differ. Many residents believe that New Orleans has a long way still to go.

There have been improvements. New evacuation policies, procedures and routes have been put in place for quicker evacuation of residents from the city, including those with disabilities and lack of transportation. Statues have been erected that mark evacuation points throughout the city were people can congregate to board buses to be evacuated out of the city in an emergency. Despite mistrust in the city towards the Army Corps of Engineers and the Flood Protection Authority, new and improved levee systems have been put into place. However, we learned through an interactive display at the Katrina Exhibit that nothing can mitigate storm surges in southern Louisiana better than the natural protection of marshes and swampland. However, this barrier is slowly disappearing.

The Lower Ninth Ward had some of the most traumatic effects from the storm. Homes were swept away, knocked off their foundation, and some residents were found drowned in their attics. On top of being a low-income neighborhood, Katrina left the community groveling for help and resources. The neighborhood is primarily African American and historically was the first neighborhood where African Americans could own homes. Many of the homes in the community have been passed down through the generations and very few had homeowner’s or flood insurance.

In a speech addressing the issues related to Katrina, President George W. Bush stated, “deep, persistent poverty in this region [with] roots in a history of racial discrimination…We have the duty to confront this poverty with bold action.” When disaster struck the Lower Ninth Ward, the neighborhood was left with very few options on how to move forward. This community was not financially sound, uninsured, and eight feet below sea level.

With so few options on how to advance, the neighborhood turned to government support and outside help. We learned of three programs that began after Hurricane Katrina to help the residents were “The Road Home” program, the “Make it Right” program, and Habitat for Humanity. Not all programs were successful or equitable. Director of lowernine.org, Laura Paul, gave us insight into the rebuilding projects within the community. “The Road Home” project initially was based on tax appraisal values, rather than the costs of rebuilding. Homes in the area had not been appraised in the years before Katrina. So residents were left without the resources to rebuild. There was a major court case lodged against the program that won. At this point, however, a lot of the money allocated to the program had already been spent, so it could not really contribute further to the rebuilding of the Lower Ninth Ward. The “Make it Right” foundation, founded by Brad Pitt, has accepted environmentally sound housing designs from all around the world. Using these designs, various homes have been built within the Lower Ninth Ward. Curtis, our navigator, who has been driving through the Lower Ninth Ward numerous times following Katrina, noted the gradual improvements within the community with each visit. Despite the advancements made in this community, there is still much to work to be done as evident by the conditions of the road including inoperable fire hydrants and open storm drains. With the efforts from long-term disaster recovery organizations, such as Laura’s, hopefully we will continue to see further development in the Lower Ninth Ward.