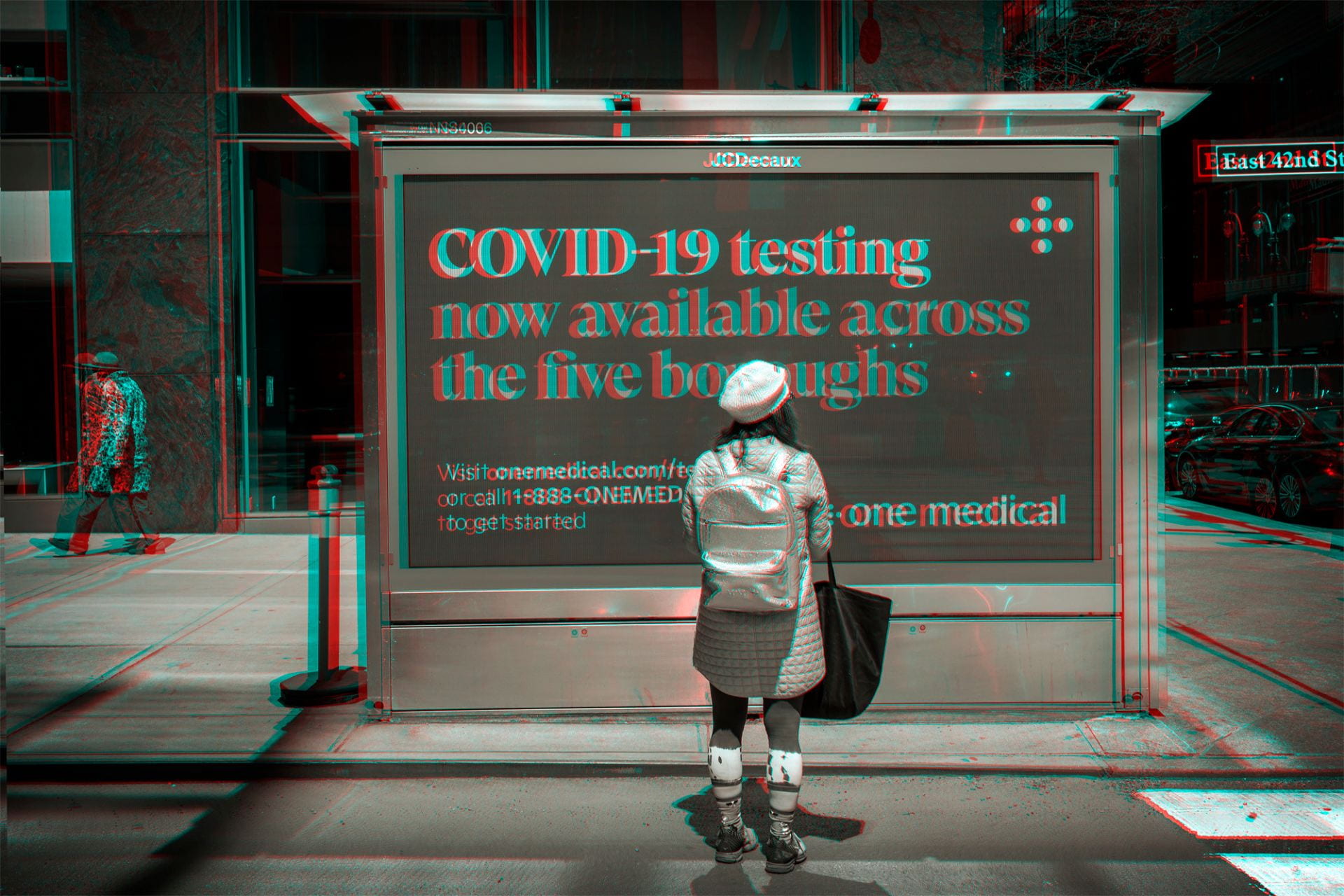

As the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) expands throughout the United States (U.S.), its impact has rapidly reached vulnerable communities south of the border. As the 10th most populous country in the world, Mexico is beginning to experience an influx in COVID-19 cases and, especially, deaths which has exacerbated many inequalities throughout the country. This blog addresses Mexico’s relevance in the COVID-19 pandemic and how it has influenced human rights issues concerning gender-based violence, indigenous peoples, organized crime, and immigration.

As of late-August, approximately 580,000 Mexicans have been diagnosed with COVID-19, while over 62,000 have died from the virus. Mexico’s capital of Mexico City is currently the country’s epicenter with over 95,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19. North of the capital, Guanajuato is nearing 30,000 confirmed cases as the second-largest hotspot, while the northern border state of Nuevo León has nearly 28,000 confirmed cases. Additionally, on the Gulf side, Tabasco and Veracruz are each nearing 28,000 cases of COVID-19. Interestingly, the southern border state of Chiapas, which has a large indigenous population, presumably has the lowest death rate (<1 death per 100,000 cases) which ignites concern about access to COVID-19 resources throughout this treacherous nation.

Gender-Based Violence

Mexico is on track to set an annual record for number of homicides since national statistics were first recorded in 1997. Femicide, which is the murder of women and girls due to their gender, has increased by over 30%. In the first half of 2020, there were 489 recorded femicides throughout Mexico. Much of this violence is attributed to the increased confinement of families since the arrival of COVID-19. For Mexican women, these atrocities are often the result of domestic abuse and drug gang activity which have both been on the rise. Regardless of how and why these acts are committed, it is plain to see that the vulnerability of women in Mexico has been exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Mexico’s President, Andrés Manuel López Obrador (often referred to as AMLO), has been notorious for downplaying the country’s proliferation of gender-based violence. Despite an 80% increase in shelter calls and 50% increase in shelter admittance by women and children since the start of the pandemic, AMLO has insisted 90% of domestic violence calls have been “false”. As part of the COVID-19 austerity response, AMLO has slashed funds for women’s shelters and audaciously reduced the budget of the National Institute of Women by 75%. This all comes after the country’s largest ever women’s strike back in March, which AMLO suggested was a right-wing plot designed to compromise his presidency. AMLO has consistently scapegoated a loss in family “values” as the reason for the country’s endless failures while he promotes fiscal austerity during a global crisis.

Indigenous Peoples of Mexico

In Mexico’s poorest state, Chiapas, many indigenous peoples are skeptical about the COVID-19 pandemic. This is largely attributed to their constant mistrust of the Mexican government which views state power as an enemy of the people. As such, conspiracies have emerged such as medical personnel killing people at hospitals and anti-dengue spray spreading COVID-19, the latter inspiring some indigenous peoples to burn several vehicles and attack the home of local authorities. Nevertheless, Mexico has confirmed over 4,000 cases and 600 deaths of indigenous peoples throughout the country. The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) suggests fostering better relationships with traditional practitioners can help limit the spread of COVID-19 in indigenous populations. Additionally, community surveillance efforts and communication through local language, symbols, and images will better protect Mexico’s indigenous populations.

Recently, 15 people at a COVID-19 checkpoint in the indigenous municipality of Huazantlán del Río, Oaxaca were ambushed and murdered. The victims were attacked after holding a protest over a local proposed wind farm, while the perpetrators are presumed to be members of the Gualterio Escandón crime organization, which aims to control the region to traffic undocumented immigrants and store stolen fuel. In 2012, members of the Ikoots indigenous group blocked construction of this area because they claimed it would undermine their rights to subsistence. This unprecedented event has garnered national attention from AMLO and the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) as they seek to initiate a thorough investigation. As demonstrated, existing land disputes have been further complicated by the presence of COVID-19 and have thus drawn Mexico’s indigenous peoples into a corner of urgency.

Organized Crime

Over the past 50 years, more than 73,000 people have been reported missing throughout Mexico, although 71,000 of these cases have occurred since 2006. Frequently targeted groups are men ages 18-25 who likely have a connection with organized crime and women ages 12-18 who are likely forced in sex trafficking. This proliferation in missing persons is largely attributed to the uptick in organized crime and drug traffic-related violence that has plagued the country. Searches for missing persons have been stalled since the arrival of COVID-19 which counters the federal government’s accountability, namely AMLO’s campaign promise to find missing persons. AMLO insists that the government countering the drug cartels with violence, like Mexico’s past administrations, is not the answer. However, many analysts argue his intelligence-based approach has emboldened criminal groups, namely with homicides, during the COVID-19 pandemic.

On the other hand, with many Mexicans unable to work and put food on the table, drug cartels are stepping up to fill the void. The Sinaloa cartel, which is one of Mexico’s largest criminal groups and suppliers of Fentanyl and heroin, has been using their safe houses to assemble aid packages marked with the notorious Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán’s liking. Although this tactic has long been used by the drug cartels to grow local support, the COVID-19 pandemic has served as an opportunity to further use impoverished Mexicans as a social shield. These acts of ‘narco-philanthropy’, which is one of the many weapons employed by the drug cartels, has enraged AMLO who has relentlessly defended his administration’s response to COVID-19. This irony reveals how growing incompetence from Mexico’s government has left its people vulnerable to not only the pandemic of a generation but more drug cartel activity.

Immigration

With the U.S. government extending its border closures into late-August, tensions mount for the migrants who seek a better life in the U.S. In addition, with a growing number of COVID-19 cases in Arizona, California, and Texas, governors from Mexico’s northern border states have demonstrated reluctance to let Americans enter the country. These reciprocal efforts have made it exceedingly difficult for migrants, namely from Haiti, to seek asylum. As a result, the Mexico-U.S. border town of Tijuana has become a stalemate for 4,000 Haitian migrants in addition to another 4,000-5,000 in the Guatemala-Mexico border town of Tapachula. This has contributed to an economic crisis where there is no work available and people face the risk of being promptly deported, effectively nullifying their treacherous journey to Mexico.

Many undocumented migrants are afraid to visit Mexico’s hospitals due to fears of being detained which would introduce harsh living conditions that put them at greater risk of COVID-19. Across from Brownsville, Texas, in the Matamoros tent encampment, aggressive isolation efforts were enacted after it was discovered that a deported Mexican citizen had COVID-19. To curtail to risk of COVID-19, the mostly asylum seekers are now expected to sleep only three-feet apart, head-to-toe. On the other hand, some Mexican nationals are crossing the Mexico-U.S. border into El Paso, in addition to Southern California, under the travel restrictions loophole pertaining to medical needs. This influx is largely attributed to the lack of resources, such as oxygen and physical space, seen in many Mexican hospitals. As such, COVID-19 resource limitations are endured by both asylum seekers and medical migrants.

Human Rights in Mexico

As shown, issues notoriously attached to Mexico, namely femicide, indigenous autonomy, organized crime, and immigration, have been further complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Femicide has grown due to a culture of misogyny that has proliferated during the lockdown. Indigenous communities have developed more distrust for the federal government, particularly as it relates to public health and land rights. Organized crime groups have extended their reign of terror on the Mexican people by weaponizing the effects of COVID-19. Immigrants, mainly from Central America and the Caribbean, are not only running from their dreadful past but also face the challenging prospects of a world with COVID-19.

As a global influence, Mexico fosters the responsibility to uphold international standards related to women’s rights, indigenous rights, and immigrant rights. Despite each of these issues having their own unique human rights prescription, they could all be improved by a more responsive government. This has rarely been the case for AMLO who has consistently minimized the urgency, and sometimes existence, of human rights issues in Mexico. Furthermore, austerity measures provoked by COVID-19 should not come at the expense of Mexico’s most vulnerable populations because they exacerbate existing inequalities and serve as a basis for future conflict, insecurity, and violence. One of the most important ways the Mexican government can limit these inequalities is by properly addressing the war on drugs which includes closing institutional grey areas that foster crime, strengthening law enforcement, and ensuring policies carry over into future administrations. All the while, the U.S. must address its role in Mexico’s drug and arms trade. Confronting these growing concerns from both sides of border is the only way Mexico while encounter a peaceful, prosperous future.