The Russian invasion of Ukraine has devastated both nations, with the people of Ukraine struggling to defend their homes against the more advanced Russian military, the people of Russia struggling financially in the face of global sanctions, and has spread anxiety to many nations of the possibilities of another world war, or even worse, the escalation into nuclear warfare. While there is a lot of coverage regarding the many attempts at diplomacy, the bombings and other military attacks on Ukraine, and the reactions of both Vladimir Putin, the Russian leader, as well as Volodymyr Zelensky, the Ukrainian leader, there are many consequences of this crisis that need to be brought to attention. It is important to focus on the impact of this crisis on the civilian populations of both nations and equally important for people to recognize that this crisis, along with similar crises around the world, is further fueling the climate crisis, even without the threats of nuclear warfare dangerously being dangled as an option. Additionally, the Ukrainian forces of resistance are essentially complex; on one side, ordinary Ukrainian citizens should be honored for their bravery and resistance at defending their nation from foreign invasion, but on the other hand, it is necessary to recognize that the Ukrainian military also includes the Azov Battalion, the neo-Nazi Special Operations unit in the Ukrainian National Guard. These are some delicate times, and transparency can help increase the trust among nations. Just the same, in the wake of this crisis, the world should not ignore the other brutalities taking place globally, many of which have participated in egregious violations of human rights. Finally, it is pertinent that people be aware of the war crimes and crimes against humanity committed by Russia and hold them accountable.

The Human Impact

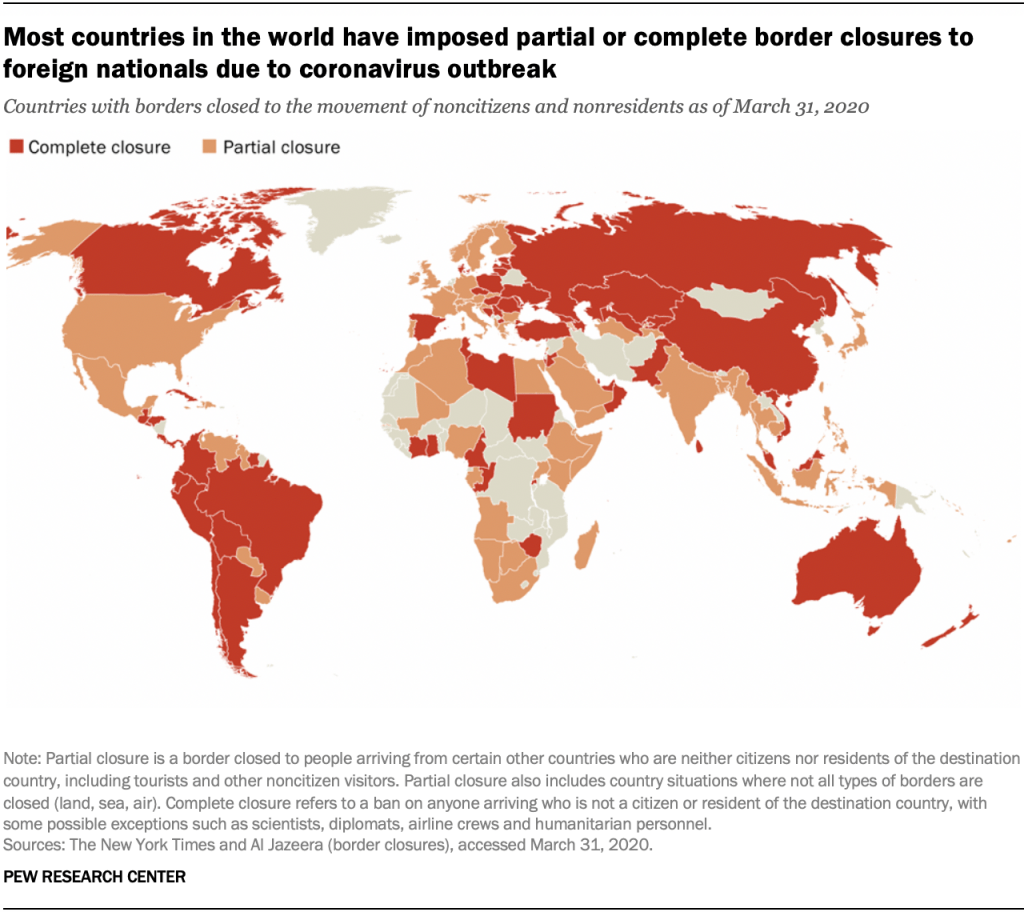

While this crisis is a result of drastic measures taken by Putin and as a response to Putin’s aggressions, Zelensky, the civilian populations are the ones that are most impacted by it. On the one side of the conflict, Russian civilians are facing tremendous economic struggles, as sanctions are being placed on Russia from countries throughout the world. Among those who placed sanctions against Russia were the European Union, Australia, Japan, and even the famously neutral Switzerland. The European Union promised to cause “maximum impact” on Russia’s economy, some states like Japan and Australia chose to sanction the oligarchs and their luxury goods, and the United States sanctions included a freeze on Putin’s assets. With that being said, it is important to analyze how these sanctions can harm everyday Russian citizens. Civilians are lining up at ATMs and banks to withdraw their cash as stocks are plunging and the Russian currency, the Ruble, lost its value by 25%. Many Russian-made products are being boycotted around the world, and even Russian participation in events like the Paralympics is being banned. Russian citizens are unable to access their money through Google Pay and Apple Pay, as both have been suspended in Russia. For fear of Russian propaganda, the United States has even banned Russian media outlets from having access to the American people. Furthermore, even amidst these sanctions and economic uncertainties, Russian civilians have risked their lives to protest against their leader and the Ukrainian invasion in large numbers. When the invasion first began, 2,000 Russian protesters against the war got arrested by the Russian police. Almost two weeks into this invasion, as the protests continue to take place, as many as 4,300protesters have been arrested. Shockingly, many of the Russian soldiers sent to invade Ukraine have been reported abandoning their posts, fleeing or voluntarily surrendering to the Ukrainian forces, admitting that they were not even aware they were being sent into combat. These Russian soldiers, many of whom are inexperienced, young adults, are being forced to fight or be assassinated by their officers for abandoning their military posts during active wartime.

Nevertheless, as a result of Putin’s aggression, on the other side of this conflict, Ukrainians are being forced to deal with the devastations of war, and the people of Ukraine are fully invested in the defense of their nation. Ordinary citizens are being taught how to make Molotov cocktails, civilians are coming together to help each other meet their basic needs and anyone capable of fighting is being recruited to join the Ukrainian defense forces. Unfortunately, Ukraine has banned 18 to 60-year-old men from leaving the nation and forcing them to join the fight. This wartime crisis has also led to a massive refugee crisis as women and children and people of other nations are trying to escape the conflict zones. This refugee crisis has its own issues, with reported instances of discrimination against refugees from the Global South fleeing Ukraine. These reports focus on the mistreatment, harassment, and restriction of the refugees from leaving Ukraine to seek safety. Additionally, while the global solidarity to support Ukrainian refugees is admirable and should be commended, many critics have argued that Ukrainian refugees have been better received from the rest of Europe and the rest of the world in general, while refugees from the Middle East or other Global South nations have not been treated with the same courtesy. These are some valid points to consider, and the refugee crisis is only going to be amplified as a result of the many consequences of climate change.

Warfare and Climate Change

Climate change continues to impact the world during this crisis. The latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) illustrates just how fragile our current climate crisis seems to be, exclaiming that anthropogenic (caused by humans) climate change is increasing the severity and frequency of natural disasters, and warming up the globe around 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit). The planet is already experiencing irreversible changes, the IPCC warns, and if actions are not taken to limit emissions and combat the climate crisis, the future of humanity is at risk. Additionally, another finding was reported about the Amazon Rainforest, (popularly dubbed the “Lungs of our Planet”), being unable to recuperate as quickly as it should due to heavy logging and massive fires it has experienced just over a couple of decades. These shocking revelations should be taken seriously, as this development will lead to more conflicts over land and resources. As people around the world are beginning to experience the calamities of climate change, nuclear warfare would maximize its destructions. With Russia being a nuclear state, tensions are surmounting globally, as nations continue to condemn Putin’s aggressions, and call for a ceasefire. Putting aside the possibilities of nuclear warfare, regular warfare amplifies the climate crisis in many ways.

First and foremost, warfare and military operations have a direct correlation to climate change in that they use massive amounts of fossil fuels to operate their machines and weapons, and militaries are among the largest producers of carbon across the world. This means that not only do militaries and their operations consume massive amounts of fossil fuels, but they are also among the biggest polluters in the world. Militaries worldwide need to decrease their carbon footprints and engage in more diplomatic strategies instead of engaging in warfare. We need to focus on international efforts to combat climate change and transform our economies and infrastructures into sustainable ones that rely on renewable resources. With this in mind, Germany addressed the energy crisis in Europe by suggesting that there needs to be a shift to a more sustainable economy, away from the influences of Russia, with the intentions of also fighting against climate change while becoming economically independent from Russian resources.

Furthermore, Russia, on the first day of its invasion against Ukraine, captured the site of the nuclear disaster, Chernobyl. While many argue that this was a strategic move to provide Russian troops a shortcut into Kyiv through Belarus, (Russia’s allies), others argue that the capturing of Chernobyl was meant to send a message to the West to not interfere. Still, others believe that the capture of Chernobyl held historic relevance, as many believe that the incident at Chernobyl led to the fall of the Soviet Union. Whatever may be the case, it is unclear what Putin’s plans for Chernobyl are, and as an area that is filled with radioactive, nuclear waste, people’s concerns with Putin’s possession of Chernobyl seem valid. If not contained and treated with caution, the nuclear waste being stored at Chernobyl can cause irreversible damages to both the environment and nearby populations for decades. Recently, there have been reports of Russian attacks on the Zaporizhzhia Ukrainian nuclear power plant which caught on fire, increasing the risks of a disaster ten times as bad as Chernobyl was. While we are still unclear as to the details of this report, we do know that Russia has captured it, and at the very least, wants to hinder Ukraine’s source of energy. Ukraine depends on nuclear energy for its electricity, and this plant produced 20% of the nation’s energy. At best, this was a strategic move on Russia’s part, yet some have even suggested that if Putin is so irresponsible with his attacks on a nuclear power plant, how much restraint might he show with regards to using nuclear weapons if he feels pushed into a corner.

Finally, as was explored during the Cold War, nuclear weapons themselves have dramatic consequences on the planet as a whole and have the power of ending humanity. This was one of the major epiphanies that led to the de-escalation of the Cold War when both the United States and the Soviet Union understood that to use nuclear weapons against each other would be “mutually assured destruction.” While many argue that Putin’s instructions to ready Russia’s nuclear weapons is a form of intimidation targeted on the West, these threats can carry out unimaginable consequences if acted upon. With increasing pressures from all sides, including the global sanctions, and the massive resistance from Ukraine, Putin’s incentives are becoming unclear as this conflict continues to unfold.

The Complexities of the Ukrainian Crisis

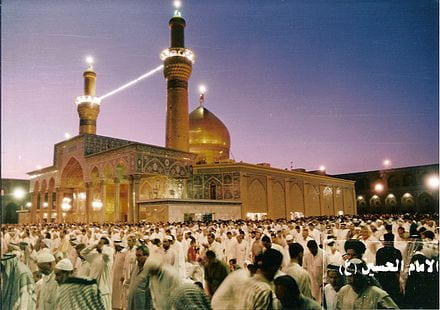

There has been a backlash by some that the world was not this enraged when similar invasions and occupations occurred in Palestine, Syria, or during several of the Middle Eastern conflicts that have devastated the people of that region. Still, others have dismissed this argument, stating that what makes this crisis especially relevant globally is its threats of nuclear warfare. Others, however, argue that the global support of Ukraine is in part due to their being a population of white Christians. To support this argument, they point to many instances in Western media coverage of the Ukrainian invasion that has suggested this exact idea. A CBS reporter cried on a news segment, “this isn’t a place, with all due respect, like Iraq or Afghanistan, that has seen conflict raging for decades. This is relatively civilized, relatively European….” Even a Ukrainian prosecutor was caught saying “It’s very emotional for me because I see European people with blue eyes and blonde hair being killed.” This is important to note because Ukraine’s military has a Special Operations Unit known as the Azov Battalion, which is made up of far-right neo-Nazis, sporting Nazi regalia and symbols of White Supremacy. Putin’s many excuses for invading Ukraine included the need to “de-Nazify Ukraine”, referring to Ukraine’s empowering of the Azov Battalion’s rise to military and political prominence in the country. The Azov Battalion came under fire in 2016 for committing human rights violations and war crimes, detailing reports of abuse and terrorism against the civilians of the Donbas region in separatist Ukraine. With that being said, Putin’s excuse of wanting to terrorize an entire nation for the sake of his opposition to one particular group of Ukrainians is not justified, and people argue that his motivations are much more insidious than that. With the Ukrainian crisis being such a complex and nuanced issue, much of the world is focused on the conflict, a reality that many nations are taking advantage of to benefit their own national interests.

Other Aggressions still taking place around the world

While the world’s attention is captured by the Ukraine-Russian crisis, some countries are taking advantage of a distracted world to commit their own atrocities. For one, Palestine continues to be colonized by Israel, a struggle that has lasted for over fifty years now. While Israelis are showing solidarity for Ukrainians from occupied Palestinian lands, they are oblivious to the hypocrisy of their actions and refuse to recognize their role in the suffering of the Palestinians. Just a few days ago, Israeli forces attacked and killed Palestinian civilians in the occupied West Bank, and they continue to terrorize the Palestinians in an attempt to force them out of their homes.

In another part of the world, the United States, while calling for peace in Ukraine, proceeded to bomb Somalia in the past week. A conflict that the United States has been a part of for fifteen years now, American forces claim that their intended targets are the militant groups in Somalia. Yet, according to Amnesty International, the US African Command admitted to having killed civilian populations with one of its many airstrikes conducted over Galgaduud in 2018. In fact, they claim that the only reason the US even admitted to the civilian casualties in Somalia was due to extensive research on the part of Amnesty International.

The Ukrainian conflict also has Taiwan on the edge of its seats, as many are focusing on the US response to the Ukrainian invasion to measure the reactions that the US might have if China were to invade Taiwan. Many Taiwanese officials are contemplating Russia and China’s close relationship and are worried about what a successive Russian invasion of Ukraine might mean for their own development with China. The Chinese government is already engaging in misinformation/disinformation campaigns against Taiwan, and many Taiwanese claims that China has also been conducting cyberattacks in Taiwan and military drills around the island.

Resistance and Accountability

Ukrainians, much to Putin’s dismay, have been successfully defending their nation and holding off Russian forces for over a week now. In response to its successful resistance, Ukraine’s forces claim that the Russian bombings have been targeting civilian buildings and taking the lives of innocent civilians, among them at least fourteen children. As videos of the Ukrainian invasion surface on social media platforms such as Tik Tok and Twitter, many experts are suggesting that the Russians are engaging in war crimes and crimes against humanity, and the International Criminal Court (ICC) has begun an investigation into these possibilities. The ICC is focusing not only on recent attacks against Ukraine but seem to also include past Russian aggression against Ukraine in their investigation. These crimes include the violation of the Geneva Convention, the bombing of civilian infrastructures, and even Russia’s use of vacuum bombs, (otherwise known as thermobaric bombs), which are bombs intended to suck the oxygen out of the air in its surroundings and convert it into a pressurized explosion. Although the vacuum bombs have been used in various places since the 1970s, (by Russia against Chechnya in 1990, by the Syrian government in 2016, and even by the United States in 2017 against Afghanistan), experts warn that these weapons can be extremely lethal and destructive in densely populated areas. Along with the above-mentioned violations against human rights, Russia’s attack on the Ukrainian nuclear power plant is added to the list of war crimes and crimes against humanity committed by Russia, and it continues to grow as the invasion persists.

Even with these threats and unprovoked aggression from Russia, Ukrainians have been more resistant than Putin had planned. Ukrainian civilians have taken up arms to defend their nation, and their enormous bravery is inspiring to witness. This sense of solidarity among the Ukrainian people is, many believe, a direct result of President Zelensky’s own courage and his choice to fight alongside his people instead of fleeing to safety. This action alone has emboldened the Ukrainian morale, and everyone is attempting to do their part in this conflict. People are helping each other out with humanitarian needs like securing food and shelter, and civilians are constructing Molotov cocktails to throw at the incoming Russian forces to stall their advances. Zelensky even released Ukraine’s prisoners and armed them, urging them to fight and defend the nation. These instances of Ukrainian resistance and unity among other nations of the world give us hope that they have a chance at winning global support against this crisis and bringing about peace and stability in the Ukrainian regions under attack. Considering the real threat of another world war unfolding before our very own eyes, it is important now more than ever, that we approach this conflict as objectively as possible. In order to do so, we have to employ different approaches that we have never before attempted and think outside of the box. With their efforts at resisting the invasion, Ukrainians have inspired me to believe that we as humans might be able to come together globally and perhaps tackle the climate crisis as well and protect our planet in the same manner the Ukrainians are defending their own homes before it’s too late.