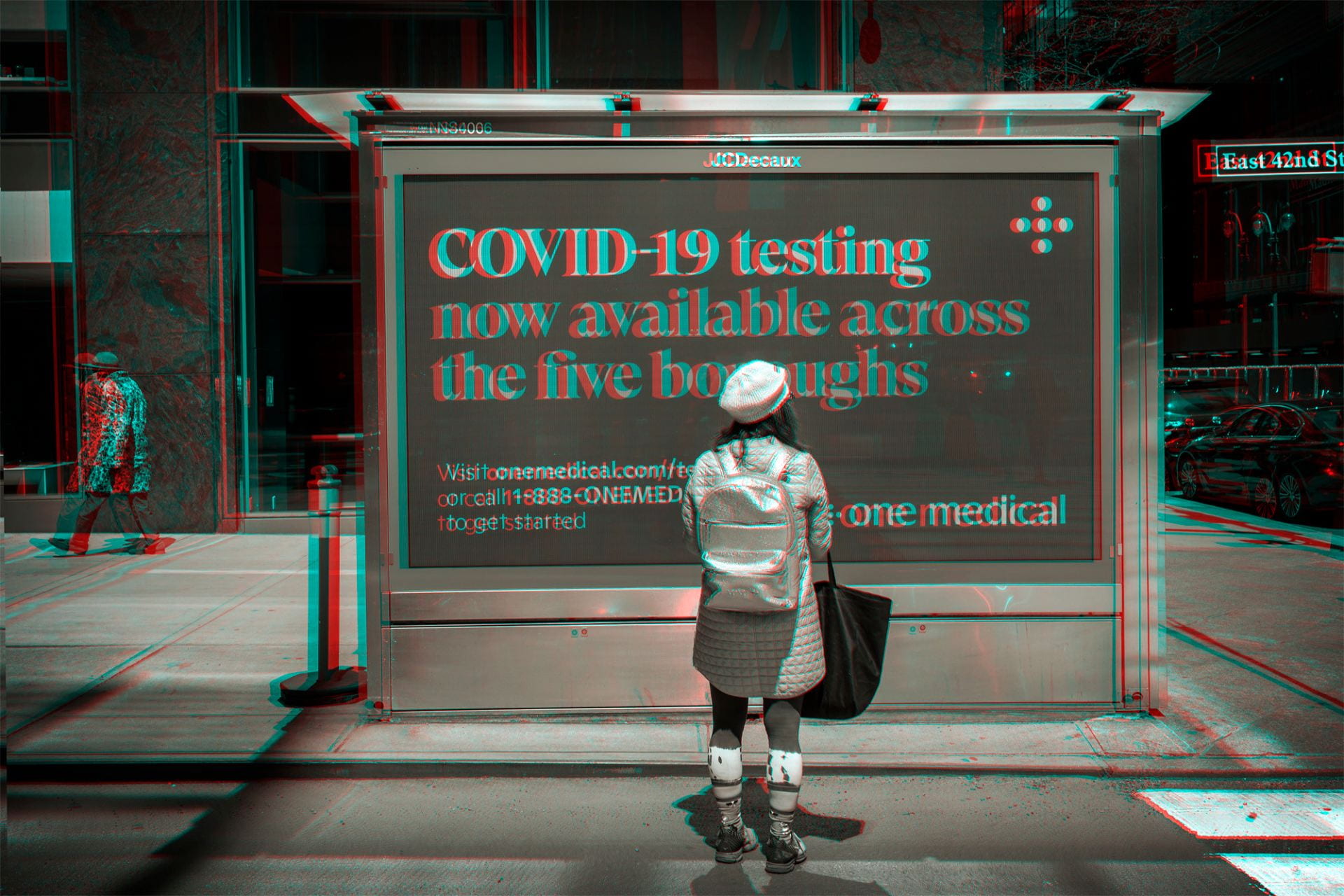

My most recent article described an overview of the opioid addiction crisis from a human rights perspective. You can view it here. In this article, I attempt to explain the different solutions from medical professionals regarding opioid addiction and the racial and economic disparities that have arisen amongst the most successful solution.

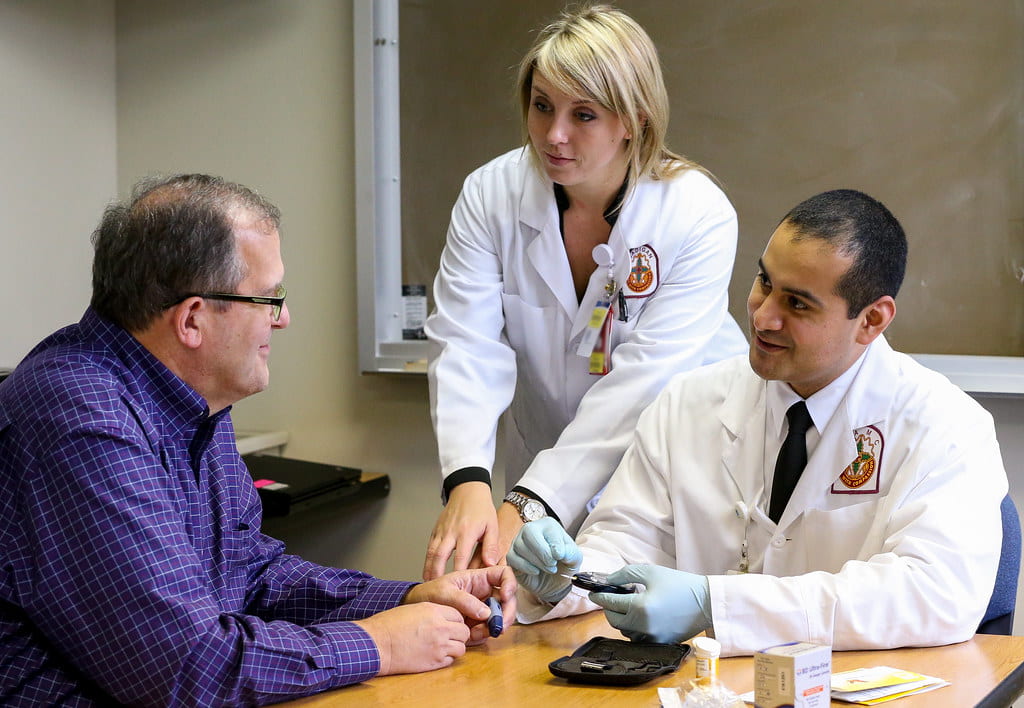

There are two forms of treatment that most clinics can decide between: traditional counseling therapy with a focus on mental strength or using medication, such as buprenorphine and methadone, to combat addiction. Research has proven that without medication, people are twice as likely to die from an overdose. However, the traditional counseling methods have persisted across treatment centers. The Journal of Substance Abuse conducted a study that showed that between 2003 and 2010, of 50,000 opioid addiction patients on Medicaid, patients who had received counseling therapies were six times more likely to relapse than those who received methadone as treatment and four times more likely than those who received buprenorphine. The risk of overdoses is increased during the period of detoxification utilized by abstinence based programs because of a lack of tolerance.

Opioid substitution has proven to reduce mortality. To avoid a misuse of buprenorphine and methadone, the two medications are tightly controlled by doctors. Buprenorphine is a drug that reduces the craving for opioids and reduces the chances of a fatal overdose overall. Suboxone, a compound of buprenorphine, is engineered to reduce the possibility of an overdose. However, using medication as treatment for addiction has only truly been utilized at a small number of walk-in clinics and has not been fully incorporated into the nation-wide health care system. In 2015, in the United States, 8-10% of treatment programs offered buprenorphine and methadone as substitution therapy. Even in this small number of programs, the method was often unsuccessful as the medicine was offered for too short of a period to be effective. The treatment is only provided in very regulated clinics and prescribers are limited to a maximum of 275 patients.

Between 2012 and 2015, the number of doctor visits where the health professional prescribed buprenorphine greatly rose. Despite this, a research report found that of 13.4 million medical cases involving buprenorphine, there was no increase in prescriptions written for minority groups. Dr. Pooja Lagisetty, one of the authors of the study, reported that white populations are nearly 35 times more likely to have buprenorphine discussed in their visit than black populations. Accessibility and insurance ability are commonly cited as reasons why this disparity has occurred, especially as the majority of white patients paid for their treatment using cash or insurance whereas only 25% of visits were covered by Medicare or Medicaid. This is especially concerning when it is taken into consideration that the rise in the use of buprenorphine occurred at the same time that opioid overdose related deaths were rising significantly faster for black populations than for whites.

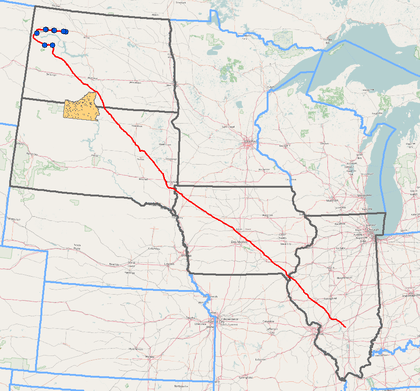

In many cities, opioid addiction treatment is segregated by income. Lower income patients find themselves needing to attend a clinic in order to receive treatment while more affluent patients are able to avoid the clinic and instead receive treatment from a doctor’s office where medicines can be prescribed. These clinic programs are federally funded and often covered by Medicaid. However, in order to receive treatment from the highly regulated clinics, patients must visit daily. Many patients commute for hours every day before waiting within the clinic to receive their life-saving medication. These patients, who are already part of a lower income bracket, are losing precious hours where they could be working or with their families. Work, childcare, families, and other related life events must revolve around the daily trip to the clinic. Some patients have described needing to turn down job offers. Because of this, methadone has earned the nickname, “liquid handcuffs.”

In order to prescribe buprenorphine, physicians are required to undergo a special form of training. Only 5% of physicians have participated in this training. The shortage of clinicians has resulted in the ability of physicians to demand cash payments in return for a prescription of buprenorphine. 40% of white patients paid cash while 35% relied on private insurance. Just 25% of these visits were covered and paid for by Medicaid and Medicare. These percentages highlight just how costly a lifesaving prescription can be for people of low income. Because of the racial disparities within the United States economy, the people who fall into this category tend to be of a minority group. Gentrification has also caused a problem within the clinic community as their buildings get bought out in favor of other businesses. In 2016 in New York City, 53% of participants in methadone programs were Latino and 23% were black, while 21% were white. Also, in 2016 more than 13,600 people in New York filled at least one prescription for Suboxone with nearly 80% of these 13,600 paid for the medication using private insurance.

Buprenorphine was purposely introduced into a private market, intended only for those who could pay a high price. Therefore, the unequal distribution of the drug can be determined to be not accidental. Due to the government regulations surrounding the prescription of the drug and the training required for doctors, there are too few doctors actually allowed to prescribe the medication. Those who can often do not accept insurance for their services as demand is so high and they can make more of a profit. Insurance will pay for the actual drug, but patients must pay for the doctor out of pocket.

A permanent stigma surrounding methadone has developed, hailing from the War on Drugs days in the 1960s. Racially charged stereotypes regarding addiction have fueled this stigma which has in turn caused lawmakers to be reluctant in passing legislation that would make the drug more accessible to underprivileged populations. However, this would be the push the community desperately needs. Medicines like buprenorphine and methadone need to be significantly more accessible, both for patients and doctors alike. They need to be included in more clinics while therapy based solely on mental counseling should be phased out from the common addiction treatment centers. In order to close the racial and economic disparities within this crisis, it is important to first recognize them. Once that has been done, our communities need to take direct action that will result in a positive change.