Continuing the Institute for Human Rights’ blog series on gun violence, this contribution illuminates a public health lens, offering an evidence-based analysis and pragmatic solutions to the U.S. gun violence epidemic.

Following the February mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School (Parkland, FL) that resulted in 17 fatalities, mainstream fervor on U.S. gun violence has, once again, returned. Parkland Students have utilized their recent tragedy as a platform to demand an end to gun violence and mass shootings, stressing why their lives matter. According to Amnesty International, the world’s largest grassroots human rights organization, U.S. gun violence is a human rights crisis. Human rights are protected and enforced by international and national policy, and with the U.S. government marshalling many of these treaties and laws, it is, too, culpable of upholding such rights.

The nation’s leading science-based voice for the public health profession, the American Public Health Association (APHA), claims gun violence is one of the leading causes of premature death in the U.S., killing over 38,000 people and injuring nearly 85,000 annually. Gun violence can not only affect people of all backgrounds but disproportionately impacts young adults, men and racial/ethnic minority groups. Recently, Parkland Students teamed with students in Chicago to address inner-city gun violence, a phenomenon commonly overlooked by the media while addressing its threat on young lives. Though most gun violence is not an agent to mass shootings, the APHA claims, in 2017, there were 346 mass shootings in the U.S., killing 437 as well as injuring 1,802.

Furthermore, the American Medical Association (AMA), who leads innovation for improving the U.S. health care system, labeled gun violence “A Public Health Crisis”. At their 2016 Annual Meeting of House Delegates, the AMA actively lobbied Congress to overturn legislation that averts the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) from researching gun violence. The CDC is one of the leading institutions of the Department of Health Human Services (DHHS), working 24/7 to protect Americans from foreign and native health threats, whether they be chronic, acute, curable or preventable, accidental or intentional. Ultimately, the CDC protects U.S. national security and critical science is imperative to addressing health threats.

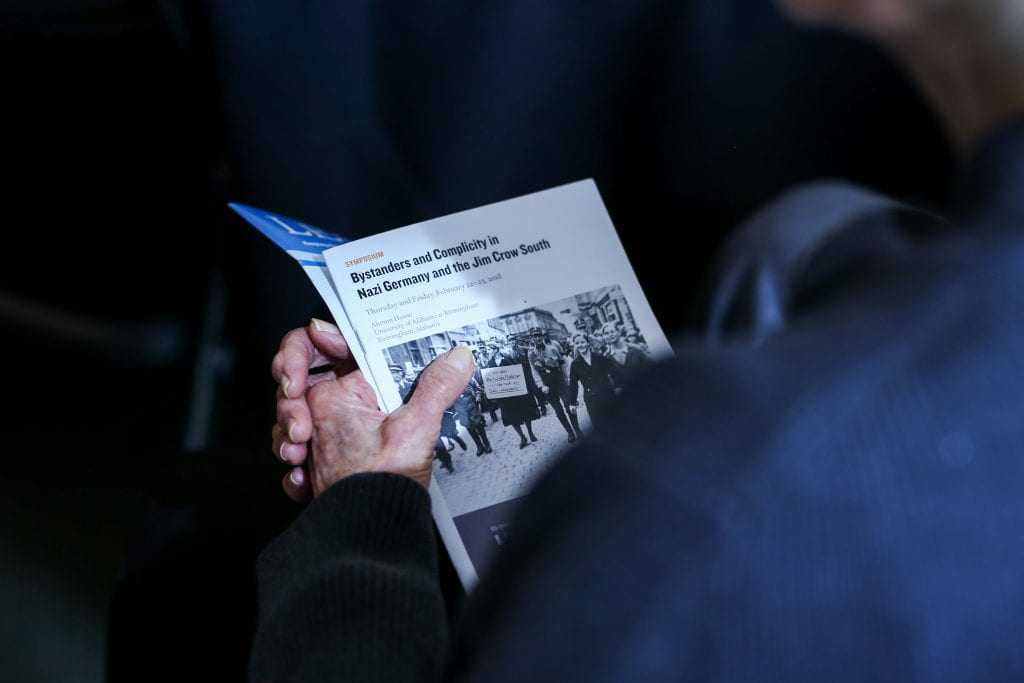

According to the Union of Concerned Scientists, a 1993 CDC-funded study published by the New England Journal of Medicine found that firearms in the home increased the risk of homicide in the household, as opposed to home protection. This galvanized the National Rifle Association (NRA), a major force in U.S. gun rights and education, to campaign against the CDC and its “anti-gun propaganda”.

In response to this 1993 publication and the NRA’s support, Congress in 1996 passed an appropriations bill known as the Dickey Amendment, named after former Arkansas congressman and NRA member Jay Dickey, which states, “none of the funds made available for injury prevention and control at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention may be used to advocate or promote gun control.” Almost two decades and thousands of tragedies later, Dickey renounced these restrictions in 2015 by claiming, “Research could have been continued on gun violence without infringing on the rights of gun owners, in the same fashion that the highway industry continued research without eliminating the automobile.” Despite this humility, the Dickey Amendment persists, curtailing efforts to address gun violence in the U.S.

In the U.S., a common method to circumvent the argument that guns extrapolate acts of violence is to scapegoat people with mental illness. The American Psychiatric Association (APA), the leading voice and conscience of modern psychiatry in the U.S., recently published a book on gun violence and mental health. Specifically, they address the topic of mass shootings and mental illness.

Some popular misperceptions are:

- Mass shootings by people with serious mental illness represent the most significant relationship between gun violence and mental illness.

- People with serious mental illness should be considered dangerous.

- Mass shooting will be effectively prevented with gun laws focusing on people with mental illness.

- Gun laws focusing on people with mental illness, or a psychiatric diagnosis, are reasonable, even if they perpetuate current mental illness stigma.

On the other hand, it is evidence-based that:

- Mass shootings by people with serious mental illness represent less than 1% of all annual gun-related homicides.

- People with serious mental illness contribute to an overall 3% of violent crimes. An even smaller percentage of them are found to involve firearms.

- Laws for reducing gun violence that focus on the previously mentioned 3% will be extremely low yield, ineffective, and wasteful of resources.

- The myth that mental illness leads to violence is perpetuated by gun restriction laws focusing on people with mental illness, as well as the misunderstanding that gun violence and mental illness are strongly linked.

However, a significant caveat related to mental illness and gun violence is suicide. The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP), who funds research and offers education on suicide, claims depression is one of the most treatable psychiatric illnesses yet is seen in over 50% of people who die by suicide. Suicide lays in the shadow of repetitive, media-frenzied mass shootings, while representing nearly two-thirds of gun-related deaths in the U.S. Harvard University T.H. Chan School of Public Health indicate a number of factors that define lethality of suicide methods, including inherent deadliness, ease of use, accessibility, ability to abort mid-attempt and acceptability — all attributable to gun ownership and usage, specifically in the U.S. To strengthen civil discourse on gun-related deaths and injuries, we must uphold a national platform for suicide prevention, too. If you or a loved one is experiencing a suicidal crisis or emotional distress, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255 (available 24/7).

Last year, researchers at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine analyzed data from the Nationwide Emergency Department (ER) sample between 2006-2014 and concluded the U.S. accumulates an annual $2.8 billion in hospitals bills from gunshot wounds, with an average ER cost of $5,254 and approximately $96,000 in follow up care per patient. This study was limited because data was only used for gunshot victims who arrived at the hospital alive; people who did not seek medical treatment or were dead on arrival were not counted. Furthermore, after accounting for lost earnings, rehabilitative treatment, security costs, investigations, funerals, etc., a 2015 Mother Jones report estimated gun violence cost Americans $229 billion annually.

The APHA insists gun violence is not inevitable but preventable, and suggests core public health activities are capable of interrupting the transmission of gun violence. Notable ways to curb gun violence are:

- Better Surveillance

- Increased congressional funding of The National Violent Death Reporting System which is currently employed in 40 U.S. states, D.C. and Puerto Rico.

- More Research

- Lifting restrictions on federal funding for research on gun violence. There is barely any credible evidence on the effect of right-to-carry laws.

- Common-Sense Gun Policies

- Criminal background check on all firearms purchases. This includes gun show and internet purchases.

- Expanded Access to Mental Health Services

- Funding for mental health services has declined, so increased financial support for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) is advised.

- Resources for School and Community-Based Prevention

- Intervention and preparedness programming to prevent gun violence and other emergencies in communities, namely schools.

- Gun Safety Technology

- Innovation that prevents illegitimate gun access and misuse such as unintentional injuries.

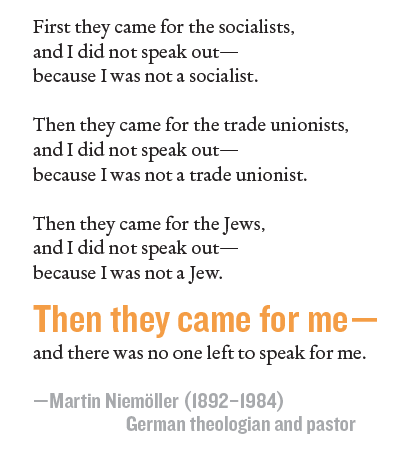

If the above prescriptions are not followed, the tragedies will likely continue. So, it is imperative we support leaders who will encourage gun policy that protects public health and our right to life. Tomorrow, March 24, 2018, people across the world will March For Our Lives, demanding the lives of kids and families, amidst the controversy circling around gun violence, become prioritized.

A march for our lives, your life and mine is exactly what the doctor ordered.