by Derrick J. Angermeier

My research seeks to answer a complicated question: Why did everyday people participate in the systems of racial oppression known historically as the Third Reich and the Jim Crow South? Historians have focused on these two national cultures and the wide variety of ways in which they excluded racialized others while elevating their own preferred racial makeups. Much of my graduate career has been spent studying the prejudice that emanated from Nazi Party leadership down to the German citizenry. However, when I took a graduate seminar on Southern History with a preeminent scholar, I was struck by the fact that, at the structural level, histories of the South resembled many of the German histories I had already consumed.

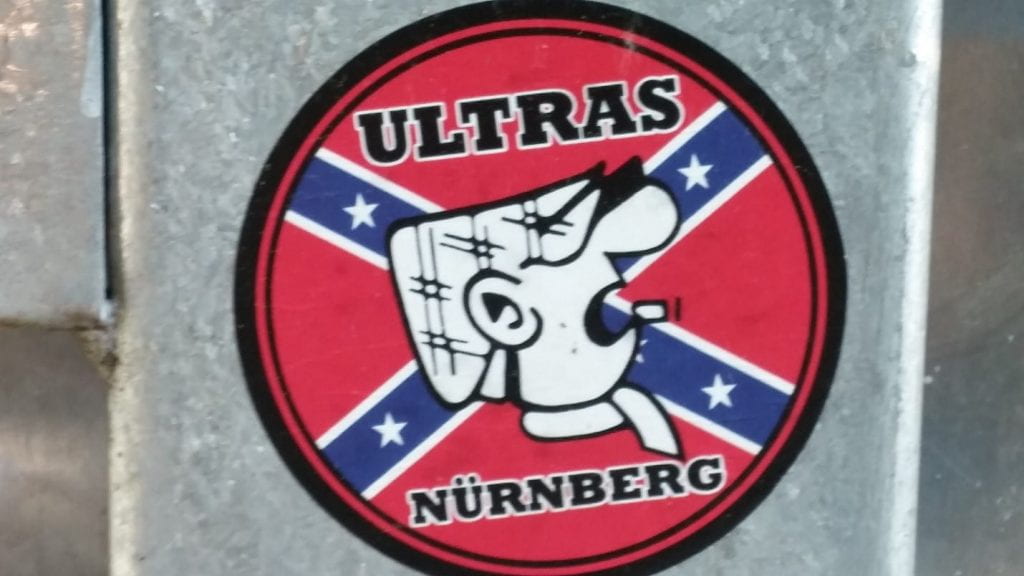

Both fields attempt to sort through complex pasts by debating continuity over time. In Germany’s case, scholars asked if there was something essentially German that caused the rise of the Third Reich by the early twentieth century? Was there a direct path from Martin Luther to Adolf Hitler, or was the development of German history more complex? Similarly, U.S. Southern academics often argued over whether the antebellum South had ever truly given way to a New South built on technology and industry. Both arguments created a self-fulfilling prophecy of sorts that has consequentially damaged historical interpretation in both fields. By setting up a world where the U.S. South was always at its heart magnolias and bigotry and Germany was always a peculiar nation susceptible to authoritarianism, no one needs to take ownership of their horrendous racial legacies. Exceptionalist narratives paint a deterministic picture where the racial castes that evolved into brutality and violence were inevitable outgrowths of inherent flaws. Nobody could help themselves; it was simply meant to be.

Such determinism has long had its opponents and supporters amongst historians, but both fields tackled this problem in remarkably similar ways: memory history. Southern and German historians embraced a historical methodology that called scholars to probe historical actors’ memories. How did exceptionalist myths like the “Lost Causes” and “Special Paths” (Sonderweg) get formed? Scholars of both cultures claimed that historical actors chose to selectively remember and internalize false memories which were then purposely perpetuated to future generations. One of the most blatant of these efforts was the United Daughters of the Confederacy, an organization defined by a desire amongst white Southern women to give permanence to the “Lost Cause” illusions of the Confederacy. Through textbooks, statues, speeches, public events, and other cultural activities the UDC ensured that a Neo-Confederate lifestyle would exist well beyond the South’s military defeat. Germany similarly internalized powerful false memories regarding militarism. Many young German men willingly went to war in the Spring of 1914 hopped up on tales of glory from Germany’s imperial wars; the fact that these conflicts were inherently one-sided and genocidal did not make it into travel accounts and youth magazines. These same myths would influence another generation; instead of seeing the First World War as brutal meat-grinder of humanity, many Germans sought glorification in the Nazi cause. False memories had indeed defined both regions and by extension their historical studies.

The more I read Southern history and reread German history I noticed more similarities. Neither regions’ academics seemed to address one another in any significant way. There were Cursory mentions here and there, footnotes in an epilogue, an occasional article. German historians and Southern historians seemed unaware of how significantly their methods of analysis overlapped. It was maddening! How could either of these places consider themselves exceptional when their histories were so painfully similar?! How had no one else really dug into this subject? The possibilities were staggering! I wrote a paper for my Southern History course on this overlap, and the whole exercise was produced more in the name of catharsis than course completion. However, the paper would not be enough, I did not find myself satisfied.

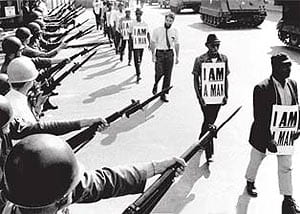

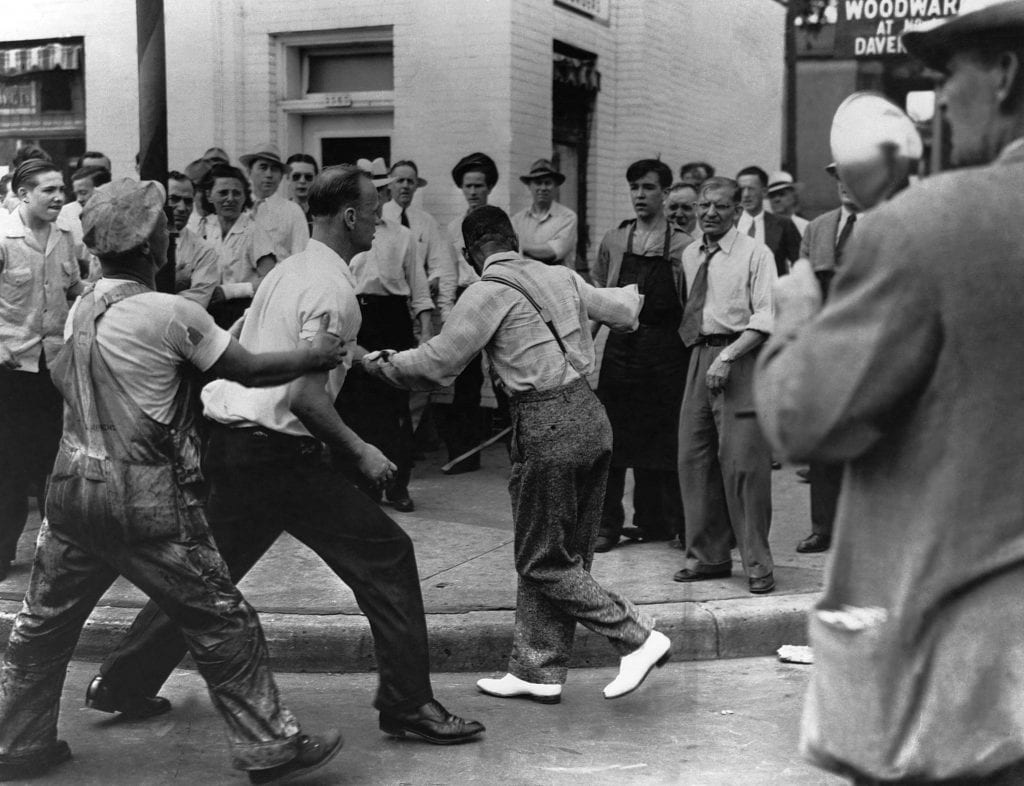

I read more and more and continued to find considerable overlap, but meaningful comparisons were few and far between. So, my new obsession slowly shifted into my dissertation proposal. I refined my original project, stripped it down to its bolts, and completely rewrote it. I added a research prospectus where I outlined my major argument, my answer to the question I asked above: Why did everyday people participate in the systems of racial oppression known historically as the Third Reich and the Jim Crow South? People were subjugated, excluded, and made the easy victims of violence and deprivation. The answer would not be found in studying politicians, demagogues, and the elites that had often defined my research. No, the similarity between these two regions, the element that formed the foundation of a transnational system of racial intolerance and exclusion was everyday people. The racial castes of Jim Crow and National Socialism may have had the force of law, but everyday people were the ones who enforced and followed the boundaries of racial propriety. Those boundaries were often set and adjusted at very local levels in countless interactions far away from any state supervision.

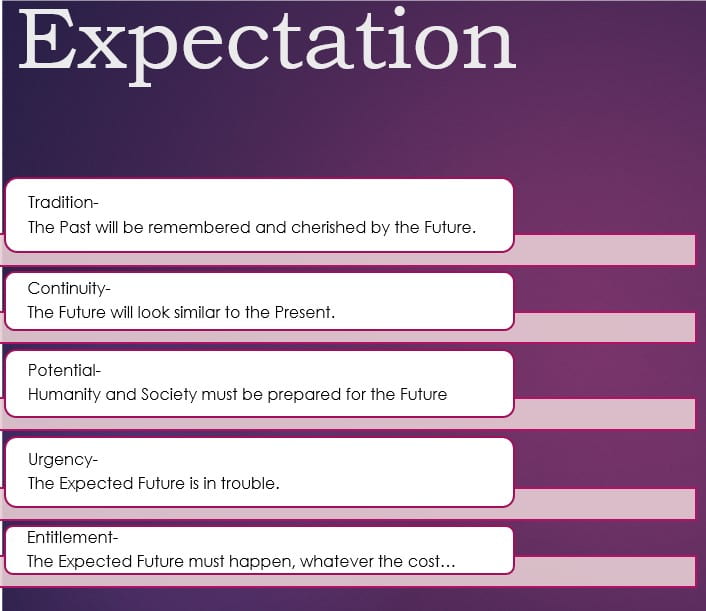

Many historians have argued that events and circumstances dictated complicity- in other words a historical actor’s present world left them little choice. Other scholars assert that historical actor’s memories of the past informed their complicity. I depart from these arguments; I insist that the answer to everyday complicity in the Third Reich and Jim Crow South lies not in past or present but in the future. I study the various expected futures that these historical actors internalized, which I call “Expectation” for shorthand. Expectation is a fact of human existence; we all walk around with some form of expectation of the future, be it a political identity, a five-year plan, or even what to eat for dinner. Historical actors similarly had expectations. In my research I have unearthed those hopes and fears of countless possible futures that provided considerable motivation for a wide variety of actions that lent credence to Jim Crow and Nazism.

Identifying and explaining expectation has been a fascinating endeavor that has taken me across six Southern states and all across the Southern German state of Bavaria. This particular German state and its people have long considered their culture to be highly distinct from the rest of Germany, harking back to an aristocratic tradition that thrived long before Prussian led unification “reconstructed” their region into a united Germany. As such, it offers a very proximate point of comparison with a Southern culture that deals with its own hatred of reconstructions. I have assembled pamphlets, newspapers, sheet music, broadsides, tourism brochures, flyers, letters, diaries, and a wide variety of everyday kitsch to assemble a clear picture of white supremacist hopes for the future. These items help illustrate a wide variety of wants, needs, and fears that informed everyday expectations for the future and by extension the justifications people internalized to vindicate their position in racialized states.

My research has shown five key components of expectation, each one of vital importance to understanding everyday complicity. First, tradition: the idea that people expect some form a remembered past will carry over into the future. Second, continuity: the hope that the institution, customs, and society of the present will continue to exist. Third, potential: the desire to maximize the potential of humanity and society to thrive in the future. These three ideas embody expectation generally and can be found outside of Jim Crow South and the Third Reich. However, the next two components help bridge the gap between expectation and complicity. Fourth, urgency: the pressing fear generated by either stressful times, political demagogy, or the perception of changes to the status quo that motivate historical actors to become more ardent in realizing their expectations. Finally, entitlement: the idea that historical actors considered themselves entitled to their expectations of the future at the direct expense of other people.

To fully explain how tradition, continuity, potential, urgency, and entitlement form expectations for the future and motivate everyday people to participate in racial states I use a series of vignettes to tackle each topic and illustrate a component of expectation as it existed in both the U.S. South and Bavarian Germany during the 1920s and 1930s. For example, to study the idea of tradition, I look at the Lost Cause and postwar Confederate worship to demonstrate that Southerners generally expected their futures to contain some vestiges of moonlight and magnolias. In Bavaria, an emphasis on agricultural roots and Bavaria’s separate monarchy demonstrate that Bavarians hoped to honor their separatism of yesteryear. In assembling this argument, I have called on debates over Women’s Suffrage, Bavarian Catholicism, white supporters of Marcus Garvey, sterilization and eugenics, the Scopes Trial, Bamberg tourism, Prohibition, and so much else to unearth everyday expectation in a clear and compelling fashion.

When we consider the factors that contributed to everyday complicity, we must not only look at the usual suspects hierarchy, heritage, racism but also reflect on the role of people’s entitlement to expected futures and the fear of losing those futures. The world of the 1920s and 1930s was truly tumultuous with the rise of communism, a global war and an epidemic that combined wiped out much of a generation, a global depression, and many other destabilizing events. People needed and craved stability; in the case of the Jim Crow South and the Third Reich, that stability was offered by politicians and demagogues in exchange for participation in a strict and violent racial system. This stability afforded everyday whites in both the U.S. South and Bavaria Germany the opportunity to achieve their desired futures and to avoid imagined apocalypses. The opportunity to realize their expectations convinced far too many people to enforce, support, or at least look the other way as African Americans and Jews were stripped of their human rights, their dignity, and sometimes their very lives.

Derrick J. Angermeier is presently a PhD candidate in the History Department of the University of Georgia. His dissertation, titled Both Hitler and Jim Crow: Lost Causes and Imagined Futures in Nazi Bavaria and the New South, 1919-1939, explores the expectations, hopes, and fears for the future held by everyday people in the U.S. South and Bavaria, Germany during the 1920s and 1930s as vehicles to understanding complicity in racialized states. Derrick has been awarded multiple research grants and fellowships which have taken him across the U.S. South and to the southern German state of Bavaria. This May he will be a Graduate Fellow of the Berlin Seminar in Transnational European Studies. Derrick prides himself on sharing his expertise and research with the public. He has spoken at multiple events sponsored by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; most recently in February 2018 when he discussed the role “Expectation” played in everyday complicity in the Third Reich and Jim Crow South at a symposium co-sponsored by the UAB Institute for Human Rights.

Relevant works

- Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (Verso, 1991).

- Kenneth Barkin, “A Case Study in Comparative History: Populism in Germany and America,” in The State of American History, Herbert J. Bass (Quadrangle Books, 1970).

- Peter Bergmann, “American Exceptionalism and German Sonderweg in Tandem,“ The International History Review, vol. 23, no. 3 (2001): 505-534.

- Fitzhugh Brundage, The Southern Past: A Clash of Race and Memory (The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005)

- James C. Cobb, Away Down South: A History of Southern Identity (Oxford University Press, 2005).

- David C. Engerman, “Introduction: Histories of the Future and Futures of History,” The American Historical Review, vol 117, no. 5 (2012): 1402-1410.

- Paul Gaston, The New South Creed: A Study in Southern Mythmaking (Alfred A. Knopf, 1970).

- Johnpeter H. Grill and Robert L. Jenkins, “The Nazis and the American South in the 1930s: A Mirror Image? The Journal of Southern History, vol 58, no. 4 (November 1992): 667-694.

- John Haag, “Gone with the Wind in Nazi Germany,” The Georgia Historical Quarterly 73, no. 2 (Summer 1989): 378-304

- Eric Hobsbawm, The Invention of Tradition (Cambridge University Press, 1983)

- Eric Hobsbawm, Nations and Nationalism since 1790: Programme, Myth, Reality (Cambridge University Press, 1992).

- Ian Kershaw, “Hitler and the Uniqueness of Nazism,” Journal of Contemporary History, 2, (2004): 239-254.

- Jürgen Kocka, “German History Before Hitler: The Debate about the German Sonderweg,” Journal of Contemporary History 23, no. 1 (1988): 3–16.

- George L Mosse, The Crisis of German Ideology: Intellectual Origins of the Third Reich (Howard Fertig: 1964).

- Wolfgang Schivelbusch, The Culture of Defeat: On National Trauma, Mourning and Recovery, Jefferson Chase (Metropolitan Books, 2001).

- Nina Silber, The Romans of Reunion: Northers and the South 1865-1900 (University of North Carolina Press, 1993)

- Martina Steber and Bernhard Gotto, eds., Visions of Community in Nazi Germany: Social Engineering and Private (Oxford University Press, 2014).

- Fritz Stern, The Politics of Cultural Despair: The Rise of Germanic Ideology. (University of California Press, 1974).

- Charles Reagan Wilson, Baptized in Blood: The Religion of Lost Cause, 1865-1920 (University of Georgia Press, 1980).

- Andrew Zimmermann, Alabama in Africa: Booker T. Washington, the German Empire, and the Globalization of the New South, (Princeton University Press, 2012).