Former Ambassador Robert Ford, on Wednesday, March 22, made a stop to the UAB Alumni House to speak on the United States’ foreign policy on the Middle East and North Africa. As a career diplomat serving the US State Department and Peace Corps for 30 years, his tenure was categorized by his reputation as a brilliant Arabist. He first served in the Peace Corps as a volunteer in Morocco and as US Ambassador to Algeria (2006-2008) and as the last US Ambassador to Syria (2011-2014). Additionally, he served on posts for the US State Department in Bahrain and Iraq. Ambassador Ford’s career was lauded by the US government, and upon his retirement, the US State Department conferred upon him the Secretary’s Service Award, the highest award honored by the State Department.

The opening slide, entitled “Not Our Business: The American Approach to Human Rights in the Middle East in the Age of American First”, foreshadowed Ford’s disdain for the current administration’s foreign policy in the Middle East. This disdain, he continuously qualified through his presentation, stems not from tangible behavior the Trump administration has enacted in the two months since President Trump’s ascendency, but from the utter lack of preparation to mindfully and successfully engage in the drama of foreign policy. The Trump Administration has thousands of positions to fill at the national level, including the Department of State; this vacuum signals to politicos a few potential assumptions about the Trump Administration. First, Trump and his cohorts do not have the necessary means (i.e. time, energy) to fill these positions. Second, individuals who may have served in other administrations have refused service in Trump’s government. Lastly, the Trump Administrations simply have not realized the pressing need of filling these vacancies. The likely explanation is a mix of all three. Ford explained “America First” is not inherently a bad or unproductive philosophy. Governments must have self-interest. The very nature of government is to protect its citizens (says the realists) and to actively contribute to a prosocial world order (says certain liberals). America First is not the problem. The problem is the infancy of the Trump Administration in its experience and insight in governing. President Trump, prior to his election, never served public office at the national level. Critics of Obama’s immaturity in governing at the national level (as he was a first-term senator when he was elected president) should be losing their minds at the thought of a complete political neophyte taking the reins of the highest elected office in the American political system. The fact, Ford argues, is the Trump Administration is in the middle of a razor-sharp learning curve on the basics of governing America. They know not what they do.

Vacancies go unfilled. This directly affects foreign policy as it would affect any office without employees. The second challenge to effective foreign policy, the Middle East notwithstanding, is the president’s desire to eviscerate the State Department’s funding. Trump reiterates a ‘no nation-building’ philosophy during his campaign; again, this is not necessarily a lack of judgement. According to Ford, former President George W. Bush’s overreach into the Middle East (among other expeditions) certainly landed America in hot water. America has retreated away from wholeheartedly committing to nation- and democracy-building interests. Some argue the pendulum has swung too far into situational interventionism. Obama’s failure in Syria to oust Assad (or effectively empower others to achieve this end) has certainly contributed to jihadism in the Middle East. The foreign policy game Obama played in Syria, one example of many, was structured around a ‘red line’ (in the case of Syria, this was the use of chemical weapons on Syrian civilians). This hardline stance can undercut flexibility; Obama couldn’t act in the case of Syria unless definitive proof implicated Assad. Meanwhile, Syrians died, jihadists recruited, and Russia peered into the situation with increasing curiosity-turned-investment. This tricky game of knowing when and where to intervene vexes every player of foreign policy, including President Trump.

The American foreign policy in the Middle East has been, and continues to be, marred with interests in diametrically opposed parties. America’s investment in Israel compels American State and UN players to willfully and knowingly ignore the stark human rights violations being committed against the people of Palestine. The American naval base in Bahrain, as in the case with Israel, incentivizes American foreign policy writers and players to ignore the repressive tendencies of the Bahraini state. Iran and the Nuclear Deal, another linchpin in American investments in the Middle East, angers Israel. The Syrian government, with the help of Russia, is still murdering Syrian citizens en masse. These are the headlines read by individuals with a keen eye for Middle Eastern politics, however this is not the full picture, Ambassador Ford argues.

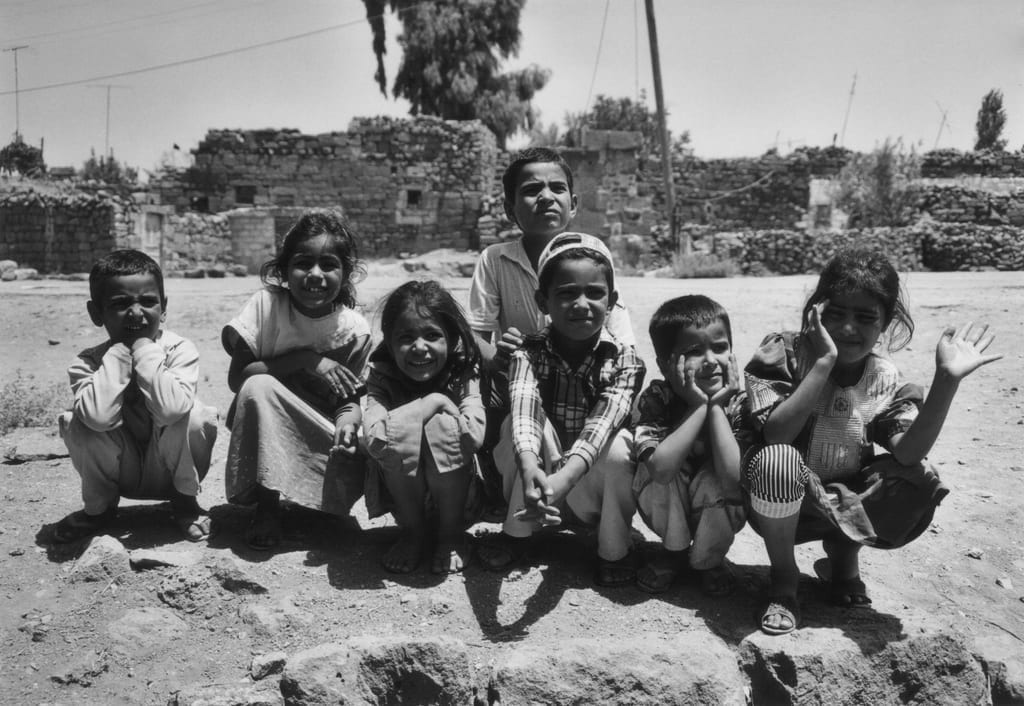

The culture in the Middle East adds another layer of complexity that is frequently ignored by self-proclaimed arabists. America has poorly interpreted and acted in accordance with the social values and cultural mores of the Middle Eastern peoples. Ford explained, drawing on his experience as ambassador, the people of the Middle East want employment, less corruption, and the relationship with their government characterized by dignity and respect. He argued collectivism, the impact of the faith of Islam, and the shadow of colonialism all shape the psyche of the Middle East. Group affiliation is a substantial psychological need in the world region; the need to belong, coupled with rising anti-American sentiments, may explain the success of Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State. Culture and politics are intrinsically linked, though some myopic policy analysts and writers take the stance that ‘never the twain shall meet’. Integration, whether between opposing US interests or in the American conception of social forces in the Middle East, is a herculean task.

Keeping these two complexities in mind, the Trump Administration’s glacial pace of governing and the convolution of Middle East politics and culture, what should the American public look forward to in the new administration? First, proposed Ambassador Ford, expect the budget cuts to soft humanitarian aid to alter the composite of human rights interests in the State Department. Institutions like USAID will be on the chopping block. Human rights, rarely discussed by the Trump Administration, will likely not serve as America’s guiding maxim in policy development. Militarization, according to Ambassador Ford, seems far more likely instead. Trump and his team advocate for substantially greater investment in the American military complex, to the tune of ~$54 billion. Although the argument could be soundly made that human right-based interests and intervention in the Middle East typically co-occurs with other American interests (i.e. oil), the Trump Administration has wholly ignored the human rights approach in US foreign policy. This philosophical and political shift may elucidate how Team Trump plans to handle crisis situations in the Middle East. Increased defense spending probably equates to increased free-floating militia to be utilized at the whim of the President and his advisors. In short, this probably leads to shift towards favoring a hard power solution in potential situations of conflict. Another alternative explanation is that Trump’s team simply has not yet created the necessary opinion required for human rights-based foreign policy. Ford argued, due to the egregiously early developmental phase of the Trump administration (coupled with lack of adequate staffing at State and other agencies), the human rights approach to the Middle East simply hasn’t been codified. For human rights advocates (and those who favor soft power approaches), this is the better scenario of the two.

Several factors will indeed influence the future relationship between America in the Middle East. Trump’s administration is new; making judgement calls on their policy and behavior is akin to putting the cart before the horse. In addition to being a new administration, the Trump administration itself is completely inexperienced to political leadership. This inexperience, when compared to past administrations, means foreign policy researchers will have to wait longer than usual for fodder to present itself for dissection. Prior engagements in the Middle East (Bush with his democracy-building and Obama with a situational intervention policy) have not only exacerbated the Middle East as a whole but have set a dangerous precedent for interventionism. Bush’s failed wars in Iraq and Afghanistan illuminate the dangers of clinging to your guns too quickly. Obama, though he favored humanitarian response over military intervention, taught policy-makers that armed intervention is necessary on occasion; look at the ‘too little too late’ case in Syria. Cultural values in the Middle East, such as the importance of family and religious identification, dictate how Middle Easterners will respond to the imposition of foreign powers, whether imposing by force or aid. Beyond these culturally relative qualities, individuals in the Middle East share common values with the rest of the world: to have a job, to raise a family, and to be treated with dignity and respect. Culture, and of course this includes the influence of Islam, determines how US forces will be received in the Middle East. The people of the Middle East wish to self-determine, according to Ambassador Ford. Self-determination may be difficult for a group of people whose lives and livelihoods have caught the eye of warmongers and bleeding hearts alike. The pressing question for President Trump and the rest of his Administration is what will help the Middle East self-determine the most: bullets, band-aids, or both?