Nationality is a privilege which is often taken for granted. For most, nationality is something that we are born into or that we inherit from our parents. In these cases, it requires little, if any, effort on our own part. Because of this, we often fail to realize that not everyone is recognized as a national by a state. You could have been born in a country and lived there your entire life, and still not be claimed by that country. This is statelessness. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), a stateless person is “a person who is not considered as a national by any state under the operation of its law.” As of 2014, there were 3,242,207 known stateless persons in the world. This does not include the numerous stateless persons who were unaccounted for. The United Nations adopted the Convention Relating to the Status of Stateless Persons in 1954 and the Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness in 1961.

People begin to experience the serious consequences of statelessness as children, when they are most vulnerable. It impedes their access to a quality education and healthcare. The effects of statelessness follow them as they grow up, keeping them from finding legal employment and taking care of themselves and their families. Statelessness is then often passed on to their children, grandchildren, and so on. It creates a vicious cycle, which is extremely difficult to break.

What Causes Statelessness?

There are numerous circumstances which may lead to person being without a nationality. Gaps in nationality laws are a significant part of the problem. An example of such a gap is seen when nationality is inherited from a parent in a specific country. If the nationalities of a child’s parents are unknown, then the child is not seen as a national of that country, and the child is stateless. Sometimes, nationality laws have discrimination built in to them. In countries like Barbados, Iraq, and Sudan, mothers cannot pass their nationality on to their children. If the father is unknown, the child is left stateless. Statelessness can also occur if new states are formed or a country’s borders change, and people are left living a different state than they originally did. For example, when Yugoslavia dissolved, the Roma people and other minorities of the area were left, struggling to gain citizenships in the states that came into existence, and continue to have great difficulty in acquiring documents for identification. There are even times when an individual’s nationality is taken away by legislation changes or if they live outside of their country for a certain amount of time.

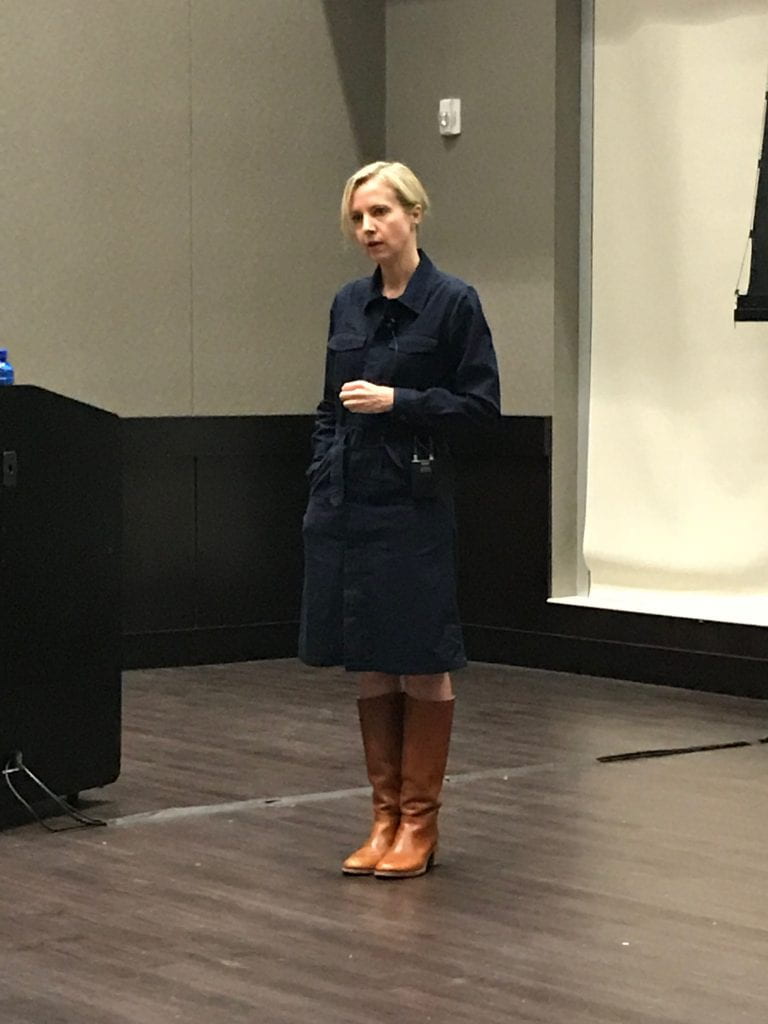

Real People

It is important that, as we discuss the issue of statelessness, we remember that this is an issue that affects real people. It is more than an abstract concept. Take Jirair, for example. Jirair was born to Armenian parents in Georgia. They moved to Russia soon after he was born but had passports from the Soviet Union (from before it dissolved) and were unable to obtain citizenship. Jirair did not legally have a nationality. He had no legal ties to Russia and no proof of his birth in Georgia. He was unable to work legally or acquire life insurance until 2016, when Georgia’s citizenship laws changed.

The entirety of the Makonde people of Kenya were stateless until 2017. Though they were originally from Mozambique, many of the Makonde people have been living in Kenya since before 1963. They lacked citizenship and any official documents. This made it difficult for them to work, travel, and even to obtain birth certificates. Generation after generation of the Makonde people experienced statelessness, vulnerable to discrimination, harassment, and poverty. Everything began to change when Kenya’s 2011 Citizenship and Immigration Act was put into full effect and the Makonde became recognized as the forty-third tribe of Kenya.

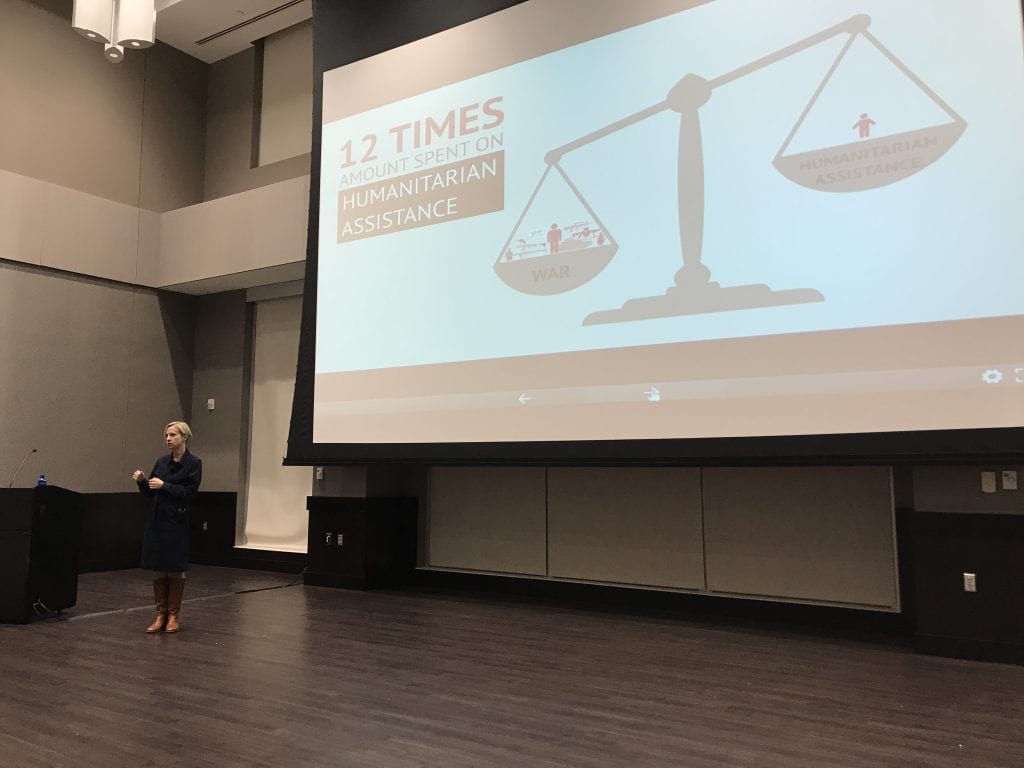

Statelessness and Human Rights

Statelessness is heavily tied in with numerous human rights violations. The first and most prominent violation is found in Article 15 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states, “Everyone has the right to a nationality.” It violates Article 23, which describes the right people have to employment, as statelessness often keeps people from working legally. Without work, individuals cannot provide for themselves or their families, and will also have an even more difficult time gaining nationality. Statelessness is also a violation of Article 25, which says that “Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and his family,” due to the poverty and lack of access to basic healthcare that result from statelessness. In order to have a quality living situation, one needs to be able to afford safe housing, a balanced diet, and basic healthcare and insurance. Many countries deny access to education to children who are not nationals of those countries, violating Article 26, which says, “Everyone has the right to education.” Education is key in a child’s ability to have a better living situation in the future and to flourish in life.

In the Convention on the Rights of the Child, Article 7 states that every child has the right to acquire a nationality. Article 24 recognizes the child’s right to “the highest attainable standard of health and to facilities for the treatment of illness and rehabilitation of health,” and Article 28 recognizes the right to an education. Children do not have access to these rights without a nationality.

The extent to which statelessness inhibits access to basic human rights makes it an issue with a severe need to be addressed. Though the rights violations it causes are reason enough to justify a change, the problem is magnified by the way statelessness impacts entire groups of people and passes from generation to generation.

Lacking a nationality also impedes an individual’s ability to participate in political processes. In many countries, such as the United States, you must be a citizen of that country in order to vote. People who are stateless have a significantly lessened opportunity to have their voice heard, especially since it is not uncommon that entire groups of people are stateless, like the Makonde people. This makes it even more important that people who do have a nationality of their own help to not only speak up and increase awareness of statelessness, but also to support a platform from which stateless people can be heard.

What Can We Do?

So, what can we do now? One of the most important things that we can do as part of the general public is promote awareness of the issue. Many people are not aware that it is even possible to lack a nationality, and more people do not know how serious the consequences of statelessness are. The more people know about the issue, the more it will be pushed to the forefront of conversations. Change cannot occur if people do not know that change is needed.

The UNHCR currently has a campaign called #IBelong, which aims to promote awareness of statelessness and work towards its end. You can sign their “Open Letter to End Statelessness,” which declares the need to end statelessness. The UNHCR also provides resources to those who are do not have a nationality. If you are stateless yourself, you can click here. You can select the country you reside in, and the website will provide you with resources that can help you on a path to acquiring a nationality, documentation that proves your nationality, or civil registration.